“America to Me,” the latest from acclaimed documentarian Steve James, is one of the year’s most remarkable achievements. Focused primarily on the lives of several young Black and biracial students, it’s not a look at what James calls a “besieged community.” Instead, the landscape is Oak Park and River Forest High School (OPRF), a well-funded center of education in an affluent, progressive community with a complex racial history. And yet the achievement gap continues to widen, without most of the obvious culprits—gang violence, severe economic hardship, lack of funding, teacher recruitment—to blame. What’s left is implicit bias, defensiveness, and perception. There are well-meaning people here, but meaning well only gets you so far. As one of James’ young subjects puts it, “This school was made for white people.”

James, a white filmmaker, knows this community well. It’s his own. He and his fellow directors turn their lenses upon OPRF High with a compassionate but unsparing eye, looking for complexity, but also joy, discomfort, but also progress. As our own Brian Tallerico puts it in his four-star review of the series, “You should know that “America to Me” is not a mournful cry for racial justice. It is often joyful. When I think of it, I think of the smiling faces of Charles, Kendale, Grant, Tiara, and the rest of the kids at OPRF. They’re just trying to get through the complex, challenging days of youth. They’re just trying to find their own definition of America. What can we, and I mean all of us, do to help them? It starts with listening to their stories.”

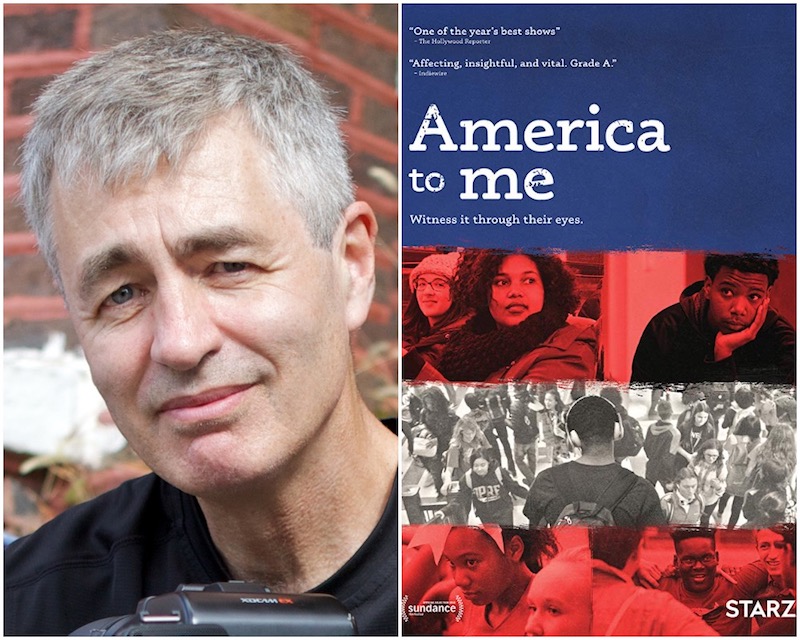

RogerEbert.com spoke with James at the Television Critics Association summer press tour about how he went about listening to those stories, the responsibilities of documentarians to tell different kinds of stories, and why having a crush on a girl in your badminton class can make for great television.

What led to the decision that you needed to take a look, in a professional sense, at what’s going on in your community—the Oak Park community?

Having lived there for as long as I have—our kids went to the high school, the last one graduated in 2010, the first one in 2006—I had this idea. Here we are, living in this incredibly liberal community that takes enormous pride in its racial history and how it managed all that, and has extremely well-funded public schools, and yet has struggled around disparities and achievement for decades. And [it] doesn’t seem to be making meaningful progress. For a long time I [thought], “how can that be?”

Because Oak Park is the kind of place where it’s supposed to work?

Right. This is the place where—and there are schools like this around the country— where, if we’re not solving it here, what’s really going on here? Because I think we all feel like we know, even when even though there’s much more to it, what’s going on in a poor CPS [Chicago Public Schools] school. When there’s no funding, in a gang-riddled neighborhood, in extreme poverty. All those are major factors that affect education, without question. But this all runs deeper than that. And you see that, in places like Oak Park. So that was a big motivator.

The other part of it was, having done films like “Hoop Dreams” and “The Interrupters” where I’ve been in those kinds of besieged communities to tell stories, I felt like it was time for me, as a filmmaker, to look at the stories of Black and biracial kids who grow up in different circumstances and try to understand what their lives are like. I don’t think, in the documentary community, we’ve told nearly enough of those stories. We have tended to focus on the most desperate, because it’s the most dramatic, and feels like it needs the most attention.

Yeah, understandably.

And I’m not disputing any of that, but I think we’ve done a disservice to the portrayal of what it means to be Black and biracial in America by not telling more stories. And it doesn’t—and I think the series shows this—it doesn’t mean just because you don’t grow up in such a desperate circumstance, that you don’t have things to struggle with in this country around race and education. So those were all factors that contributed to me, us, wanting to tell this story.

Who’s the ‘us’?

I recruited this incredible team of other director-shooters. Kevin Shaw, Bing Liu—who did “Minding the Gap,” which is out now, and a phenomenal film—and Rebecca Parrish were in the trenches with me, following kids’ stories. It was vitally important that we had a diverse team to tackle this.

This, obviously, isn’t the first time you’ve worked with kids on a documentary. Given how, as a society, our relationship to cameras has changed in the last decade—and young people in particular, they’ve got one in their pocket at all times, they can take video, they livestream—has the relationship that subjects have to the cameras that follow them changed?

I think so. First of all, I think back when I made “Hoop Dreams,” and even past “Hoop Dreams,” to other films, before the rise of the internet and social media and the ability to document your own life, document your friends, everything.

Your breakfast.

Yes, your breakfast, your important breakfast. Make sure everybody knows about your breakfast. I think when kids—and just subjects in general, adults, whoever—when they kind of gave themselves over to being in your film, they didn’t think too much. They were more revealing in some ways because they just didn’t think about those issues of what’s going to happen with this.

With what the cameras might capture?

Right. And there was lot less at stake, because if you’re in a film, it comes out, [then] it’s gone. It’s not like people go on the internet and pull it up. But this generation of young people, they know. Number one: I think they think about the fact that anything that goes out the world is out there forever. And if they’re thinking about their future, and their parents are thinking about their future, they want to be more careful about that. So that changes the dynamic.

Second: I think young people feel more agency now in terms of media. They have the ability to say, “this is who I am, and this is what I’m going to share, and this is what I’m not going to share.” So the kids are much more savvy about all that now.

Is that a challenge?

I think it’s actually a good thing. We’re not trying to make a film here about the kids’ party life, about them getting drunk on weekends. That’s not what this series is about. If you want to see that there’s plenty of examples out there. This is not about that. We didn’t care about trying to tell that aspect of their lives so much, and you know what, we weren’t going to get that.

Because the kids are more aware of how things might appear on camera?

Because the kids are much more guarded about that aspect of their lives. But I also think it’s like they’re less intimidated. They don’t have any sense of intimidation from me and [the cameras]. So I think there’s a kind of heightened ability to be candid about the stuff that they do want to talk about and speak to. So it’s different, but it’s good. I think it’s good.

Do you find, now that a couple of years have gone by, that your younger subjects are feeling differently about the choices that they made?

Yes. You know, even though I said a moment ago that kids can make certain kinds of choices about what to include and what not to include, they still reveal themselves in ways that are unexpected. I don’t know how many episodes you’ve seen, if you’ve seen the full series?

Four, but I will see the full series, yes.

Yes, make a solemn promise! You will see that there are some revealing moments for some of the kids, that—you know, I’ve always shown main subjects their scenes before it’s done, not to give them editorial control, but to have a dialogue. The films have always gotten better as a result of that. And there were some things. One of the kids, you know, she didn’t realize just how revealing she’d been, and she felt like the portrait was a little too narrowly focused on some of the trauma that she went through.

We didn’t lose that trauma, but we enlarged the portrait to make her feel like it was a better balance of who she was. We try to be sensitive to that. But for instance, Tiara—and this is not who I was just talking about here—but in the second half of the series, you see Tiara really kind of turned much more inward. She’s got stuff going on and she’s struggling in school. She’s not that kind of vivacious, really funny person. She still has that quality, but things became more serious for her. You talk to Tiara now, she’ll say, “God that was a tough year for me, and I’m not that person anymore.”

And she’s okay with that?

To her credit, she’s fine with that being seen, because she realizes that it’s important for people to see that those things happen, even though she’s not that person anymore.

I was so delighted by the moment after she auditions for the a capella group, when she’s giddy over her crush. She’s so open about it, and it was instantly recognizable. I so appreciated that yes, we see these young people confronting big things—

Grappling with race, college, exactly.

But we also get to see these kids being kids.

Yeah, it was really important to us to make the kids lives as full as we captured them, and not just use them, to let them becomes symbols or props. Not in a dismissive way, but we didn’t want to let them become the themes of race and education. Grant, starting in episode four, he has a crush on a girl in his badminton class and that story, that’s really pretty sweet. There are big issues, but also love, and nervousness, and “How do I tell her I want to go out with her?” That’s important, too.