It is fairly widely known, three months after the film’s premiere at Cannes, that Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds” has, shall we say, a surprise ending. How did Tarantino feel about rewriting history? He uses admirable logic in arguing that he did not: “At no time during the start, the middle or ever, did I have the intention of rewriting history. It was only when I was smack dab up against it, that I decided to go my own way. It just came to me as I was doing what I do, which is follow my characters as opposed to lead.”

So he told me in the course of an e-mail interview. “My characters don’t know that they are part of history. They have no pre-recorded future, and they are not aware of anything they can or cannot do. I have never pre-destined my characters, ever. And I felt now wasn’t the time to start. So basically, where I’m coming from on this issue is: (1) My characters changed the course of the war. (2) Now that didn’t happen because in real life my characters didn’t exist. (3) But if they had’ve existed, from Frederick Zoller on down, everything that happens is quite plausible.”

This argument is, to me, refreshing and actually almost logical. Every World War Two movie in history is made with audience knowledge of how the war ended. Many of them take place at a point in the war where the characters could not know, but films approaching of arriving at the end of the war do not presume to revise it. It’s a dilemma faced by Bryan Singer‘s “Valkyrie,” where Tom Cruise plays a member of a secret plot to assassinate Hitler. He doesn’t know he will fail, but we do.

In putting history up for grabs, Tarantino is audacious, but then audacity has long been his calling-card. In the process, this director, who is so much in love with movie genres, blows up all of our generic expectations. It’s quite an explosion.

“Inglourious Basterds” opens in North America on Friday, bringing with it the Best Actor award from Cannes for the German actor Christoph Waltz. He is probably also destined for an Academy Award nomination as Col. Hans Landa, the mannered, arch Nazi villain. He has an opening scene with Denis Menochet that is masterful. Not often does a big-scale war movie open with so much dialogue, so carefully crafted, so lovingly performed.

“It was one of the very first scenes I wrote in 1998,” Tarantino said. “How I wrote it is how I write all my big dialogue scenes. I basically start the characters talking to each other, and they take it from there. I will add that one of the reasons I never gave up on the script during the years was I knew how good that scene was.”

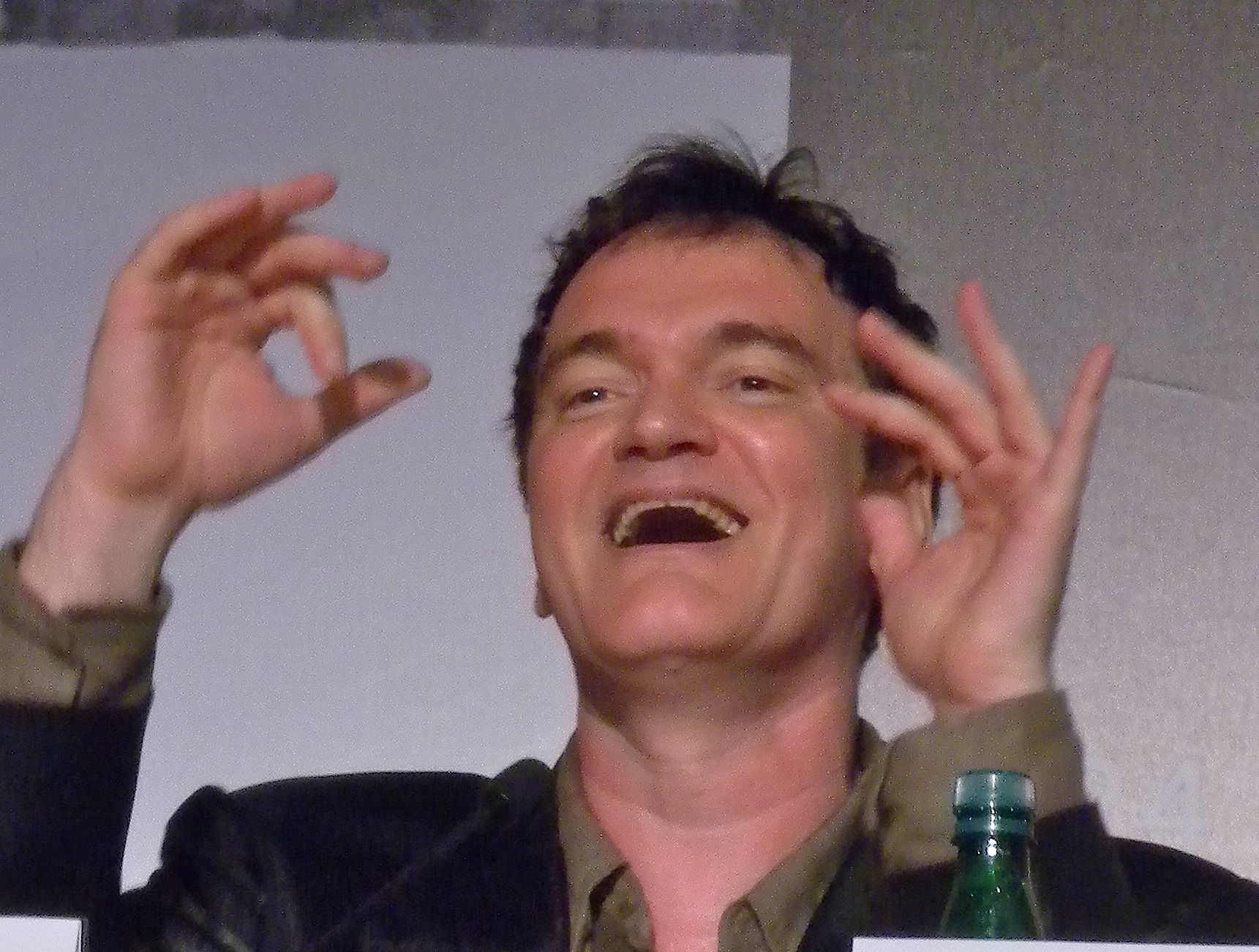

During the film’s press conference after its first Cannes screening, Tarantino said he had auditioned countless actors before Waltz walked into the room, but he sensed immediately he’d found his Hans Landa.

“Except for the opening farmhouse scene, I didn’t let Christoph rehearse with anybody else,” he told me. “All through the production, Landa was this unseen presence hanging over the characters and the actors. I wanted to keep them nervous and anxious about Landa. So I didn’t want them to know what Landa would do until we were doing the later scenes. Christoph understood that but he still wanted his rehearsal time with me, so he and I rehearsed the other scenes alone. And we had many many discussions about Landa especially about the ways and wherefores of his interrogation techniques.”

Those are mannered, I said, but not declawed. Landa toys with his foils as a cat does with a helpless mouse. There are moments when he pretends to be letting them escape, for example when he plays along with the German actress Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger), a double agent for the Allies. Observe how he compliments her and leads her on–before, so to speak, dropping the other shoe.

Tarantino’s photography of both Kruger and Melanie Laurent, who plays the heroic cinema owner Shoshanna, is striking. Von Sternberg could not have lavished more attention on Dietrich. On Shoshanna’s big night in the theater, Tarantino studies her lips, shoes, facial veil, slinky dress, cigarettes, in a fetishistic way.

“I have to admit to coming to Von Sternberg very late in life,” he said. “First, by reading a book about him which made me seek out his films for study. Then his autobiography which is I think one of the finest critical books of cinema art and its limitations ever written. Now I consider that of the cinema geniuses like Kubrick and Welles…my favorite genius is Von Sternberg. I thought I gave Kruger the Von Sternberg treatment more than Laurent.”

Laurent creates a virtuoso performance, from the frightened young girl in the opening scene to the ingénue on the ladder to the femme fatale in the projection booth.

“Ingénue, yes. But you have to believe she would kill that poor innocent film lab guy if he didn’t do what they said. Also, I like the idea that maybe this isn’t the first time [her lover] Marcel and her have had to resort to these tactics during her years of survival.”

Tarantino has always been distinctive in his dialogue. It often works to create imaginary frightening scenarios in the minds of the viewer, an effective way to create suspense. Consider in “Pulp Fiction,” for example, how lovingly the dangerous Marsellus Wallace is set up. I asked Tarantino about that stylistic strategy.

“A director I never really thought much about before,” he said, “was Joseph Mankiewicz. I always lumped him in with the Fred Zimmermans, Mervyn LeRoys, Robert Wises and William Wylers. However, I discovered him two years ago and especially when he directs his own scripts found a lot in common with him. And I believe, as much as me, if Mankiewicz were to take on a Western, a war film or a Hercules muscle man movie, it would be a dialogue-driven ‘talky’ version. The use of the word ‘talky’ like it’s a bad thing really irks me. His “All About Eve” is most definitely ‘talky.’ It’s also most definitely brilliant.”

As with all of his films, Tarantino somehow seems to avoid a single tone, freely moving among drama, melodrama, parody, satire, action, suspense, romance and intrigue? So I observed to him.

“All of the above. Except I think parody and satire go hand in hand. The only scene of actual parody, to me, would be the Mike Myers scene which is a parody of a WWII bunch of guys on a mission movie, with the big map, the big room, the opening exposition scenes. I would add comedy to that line-up, losing either parody or satire.”

I had a few more questions:

Brad Pitt speaking Italian. Fun to work on? Temptation for him to break up? I enjoyed how studious he liked to seem. You found a fine line just below over the top.

“I have to say it was Brad’s idea to go so big with the hillbilly Bojorno. And as soon as he did it, even though we talked about it, it was obvious it was right.”

With your eyes closed during the Morricone opening, you’d assume you were watching a Western. Yes?

“For the first two chapters I wanted it to be like a spaghetti Western with World War II iconography.”

Did you shoot on celluloid, or has video actually gotten that good? My opinion is celluloid.

“No f***ing way would I ever shoot on video! Celluloid all the way!”

Here is the video I took of Tarantino’s Cannes press conference, with Pitt, Waltz, Kruger, Laurent and Eli Roth:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gqhHmE0Qnj4&feature=channel_page

And this is Part Two:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rifDy_ejN0A&feature=channel_page