Where do I start? With his tattooed lady? With how he hugged the mongoloid children to coax performances from them? Perhaps with the elephant’s funeral, when the enormous casket went tumbling down the hillside, and the shanty people tore it open to get at the fresh meat inside?

These are all possible beginnings, and also the story of how he killed the women in his life. Perhaps you remember it. He did not literally pick up a gun or a knife and murder them. He allowed them to die because he could have saved them, but he did not.

I look in his eyes, and this is one story I do not believe. I do not believe he could have saved them. I think they found their dooms by themselves. But I believe all of the other stories, about the tattoos and the mongoloids and the elephant’s funeral, because those stories I have seen with my own eyes.

His name is Alejandro Jodorowsky. He is 60 years old and has white hair and a thick accent and has lived everywhere and done anything. He has drawn comic strips, and worked in the circus, and was the assistant of Marcel Marceau, the great mime, and the partner of Arrabal, the Spanish surrealist. He is a movie director, but he isn’t an ambitious young cash technician with a degree from USC and an agent at CAA. He’s out there making the kinds of movies Hollywood is too timid to make anymore–explosions of images, filmed with a burning intensity, torn from the pit of his soul.

His previous films are “El Topo” (1971), a cult classic, and “The Holy Mountain” (1972). Then he did not make movies for years, because who would finance this strange man? He is the kind of person you could listen to all night long, because in a world of safe and passionless people, this is a man who has lived many lives. Most movies are boring. His are not. His secret is, he doesn’t care if he pleases you; he makes his movies because he is driven to it.

I sat next to him at a little table looking out over the Mediterranean. We drank expressos from the cafe at the corner. I had seen his movie earlier that morning. This was in May 1989 at the Cannes Film Festival. Usually when you interview someone at Cannes, and a year goes past before the movie opens, you lose your notes or forget your enthusiasm. Not with this man. I put my notes in a safe place, and promised myself that when his movie opened I would write about it, because brave films like this get lost in the jungle of American distribution. I was going to say they get thrown out with the trash, but no — the trash opens on Friday.

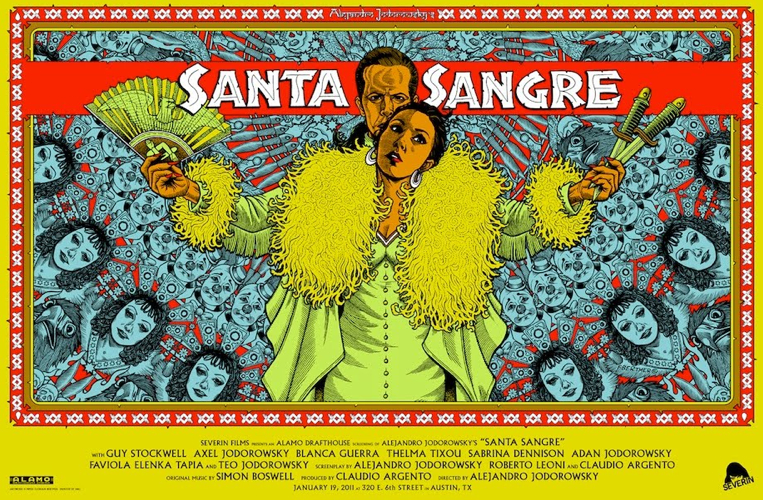

The name of his new movie is “Santa Sangre.” That comes out as “Saint Blood” or “Holy Blood.” The movie was shot in English, one of Jodorowsky’s languages, in Mexico, one of his countries. He was born of Polish Jews in Chile, lived in France, England, Canada, Japan and America, and jumped ship in Mexico City during a tour with Marcel Marceau. He doesn’t speak any language without an accent.

The movie tells the story of a boy whose parents run the circus — the “Circus Gringo” — in Mexico City. The boy’s father is a bloated swine who wears a blonde wig and lusts after the tattooed lady. His mother leads a cult of women who wear red robes that have two crossed arms sewn on their breasts — arms that have been cut off at the shoulders. They worship a saint whose arms were severed by a rapist.

One day while the boy’s mother is hanging suspended by her hair from a high-wire in the center ring, she sees her husband sneak off with the tattooed lady. She surprises them in the middle of their lust, and attacks her husband with acid. In a rage, he cuts off her arms, then kills himself, because the acid has rendered him forever useless to tattooed or other ladies. The boy goes mad, and spends years sitting on a tree stump, thinking of himself as a bird. The deaf-mute girl who was his childhood playmate rescues him,. and then he rejoins his mother in a sideshow act where he stands behind her and puts his arms through the sleeves of her dress, and provides her with the limbs his father cut away.

And there is more, including a touch of “The Beast with Five Fingers,” the movie where a man struggles for control of his own hand. But the bare plot outline makes “Santa Sangre” sound like a horror film, and in fact it is a Felliniesque, Bunuelian tragicomedy about images that obsess Jodorowsky. And it is put together with energy and power, showing us things that are not recycled out of other movies but made up for this one out of Jodorowsky’s driven imagination.

“There was something acting through me, when I was making this picture,” he told me. “All the time I was like a medium, in a trance. I was not myself. I was for two years another person, like a medium. I don’t know who did this picture. You can ask to all the persons who worked with me. I was really a monster.”

Why, I asked him, did you make this film so long after your last production?

“I was suffering from a lack of creativity. I realized a person gets evil when he is not creative. Art is a need. Without art you die, I think, but there are all kinds of art. Death is an art, you know. Japan was the first civilization to discover that the art was the center — the art of flowers, art of life, art of death. I discovered it for myself through speaking with mentally ill persons. The only way to reach them is through creativity. They need to learn how to be a clown, how to paint, how to write, and then they get better and better.”

When I talked with you a few years ago, I said, you spoke of having killed, in a symbolic sense, many women.

“Yes. It is phychological, but not only psychological. My first woman committed suicide, not with me, but 20 years after we got divorced. She ran into the Metro. She was an alcoholic. I don’t know if it was my fault, but I could have saved her. My second wife, the mother of one of my sons, died of murder. I was not with her, but I could have saved her. I think. My whole life I’ve treated women badly, let them die when I could have saved them, because I was some kind of male — what is that thing? — seductor! Now I am like a frog or a pelican, but in my time I was really, really, really beautiful.

“So when I make this picture, there is a scene where all the women come up from the grave and ask, Why did I do what I did? And I must be forgiven. After I finished ‘The Holy Mountain,’ I was so awake after six months of shooting, that I finally realized what I was doing in life, how I was hurting women. It affected my conscience. Then I stopped making pictures. I said, this is illusion. I need to work with reality, find myself, discover what I want to say, how to live, how to make a family… to live, you know?”

How old were you then?

“I was 45.”

You were living in Mexico then?

“In Mexico, and in Paris.”

You became a famous author of comic strips?

“Very famous.”

He did not shrug or smile at that, because in France comic strips are regarded as a serious art form, and whole stores are devoted to hard-bound collections of them. Jodorowsky is to French comics what Camus is to French literature.

The most compelling thing in the movie, I said, is the idea of the arms. The son standing behind his mother and providing her with arms. In your inspiration for this image, did you feel somebody else was standing behind you, or did you feel you were standing behind somebody else?

“Well, both, you know. In a way both have lost their arms. And in a movie it only seems there are different characters. A movie is a stream, like the movement of life, and it’s alive. You cannot say this is her and this is him, any more than you can say this is me and this is you. When you watch my movie, are you me — or you?”

They are your images, but they are in my mind.

“Exactly.”

You have lived for many years a very free life, sometimes very rich, sometimes very poor.

“Yes, it’s true. Ah, yes, very poor, sometimes very rich.”

In Paris, in Mexico.

“Sometimes anywhere.”

With your children.

“Five. All living with me. To make amends for my terrible performance as the father, I become now the mother, you see.”

How did you learn to live with such freedom from the ordinary responsibilities of earning a living, following a career, being predictable?

“Most people, they say, don’t burn the ships! You must always be able to return. I say no, I will burn the ships. I earned a university degree in psychology, and they said, now you have a title, now you have a job, but I burned my title, my diploma, and I started to make puppets. And from that moment, I lived for art. I burned everything I had written. I burned all my photos — I was a photographer at the time. By coincidence, my house burned down at the same time. Perfect! I made puppets. I worked in the circus. That made my life.

“I made puppets, and then marionettes, and then I did mime. I directed musicals, I directed even Maurice Chavalier, all that kind of stuff, and then classic theatre, Shakespeare, and then my first movie. When I started to pay income tax, I was 50 years old. I was a happy man, never working. Sometimes I saw days with no money to eat. It was not so difficult.”

Did you know a tattooed lady in the circus?

“Yes, in Los Angeles, completely tattooed, all over, she does exist.”

You’re obsessed with tattooing?

“Yes, when I first saw tattoos, it went inside my body. I was thinking a tattooed person can conduct me to some kind of consciousness. Then I see the Japanese picture about the tattooed woman, her lover made her be tattooed all over.

“Irezumi?”

“Yes! I loved it. I loved it! And then I met that tattooed woman in Los Angeles. She was really tattooed, and she was an exhibitionist. She liked to show her tattoos, but she had no talent for me. So I designed my own tattoos for the woman in my film. I wanted only primitive scenes, stars, moons, tigers, lions. No symbols.”

In the movie, many of your characters seem to really be what they represent. The mongoloid children are obviously real. What about the deaf girl? The prostitutes?

“The girl is a real deaf mute, Sabrina Dennison, an American, I found her in a play about Helen Keller. The prostitutes, yes, all the ordinary people you see in the movie are real — not actors. I shoot in the streets. The mongoloid children, at times it was impossible to control them, but I took them in my arms, and I said to my actors, take them in your arms, and make contact with them, for a half an hour, one hour. Then it was very easy to work with them. That was the technique.”

When your first film, “El Topo,” came out in 1971, I said, it was an enormous hit. It played as a cult film all over the world. Then it disappeared. It’s not even on video.

“It is Allen Klein who made it disappear. He used to be with the Beatles. He owns the rights to it. That guy, he says ‘El Topo‘ is like wine, all the time it gets better. He says, ‘I am waiting until you die, and then I am going to have a fortune.’ I hope he dies before me. Seriously. That guy is waiting for my death. He thinks he’s immortal.”

How old is he?

“I don’t know, about 50 years.”

But you will live longer.

“I hope so. If he dies first, I get the film back.”

Why did you make a deal like that?

“Because at that time, I was not thinking in business. I was thinking to direct a picture. I got 10 percent of nothing.”

He laughed.

Everyone who saw “El Topo” remembers it, I said, but now it’s almost 20 years ago, and a new generation has never heard of it.

“That man is a carnivore, a vulture.”

There’s money to be made for everybody in the video market…

“Yes, but he doesn’t want this. He’s waiting. He’s a vulture.”

Have you talked with him recently?

“For 15 years I’ve tried to talk to him by telephone, and he’s always busy. He eats the smoking meat. Smoking meat…you know? From the delicatessan?”

Smoked meat?

“Yes. When I call him by telephone they say to me he’s eating the smoking meat. I cannot speak with him because he is eating the smoking meat.”

He eats a lot of smoked meat?

“He’s eating for 15 years the smoking meat.”

The smoked meat somehow put me in mind of the elephant burial in the movie, when the circus elephant dies and they put it in a casket and parade it through the streets and push it over the edge of a gorge, and the wretchedly poor people on the other side run down to get the elephant meat.

“That place is real,” Jodorowsky said. “The persons who eat the elephant are real, too. They are poor persons, and they cover themselves with clay, and when I showed them the meat, they growled like this: Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrr!!!”

Did they really eat the meat?

“They really ate the meat, but it was not elephant meat. I do not want to disappoint you, but in the coffin was not a real elephant. But I put in 200 kilos of meat, for them to eat. I said action!, and they all ran down like I wanted them to, because they wanted the meat. In the picture it seems surrealistic but it’s true. They ran down to get the meat.”

And was there symbolism there?

“Running down to tear open the coffin and eat the meat?”

Yes.

He smiled and spread his hands. Some symbols a man does not need to explain.