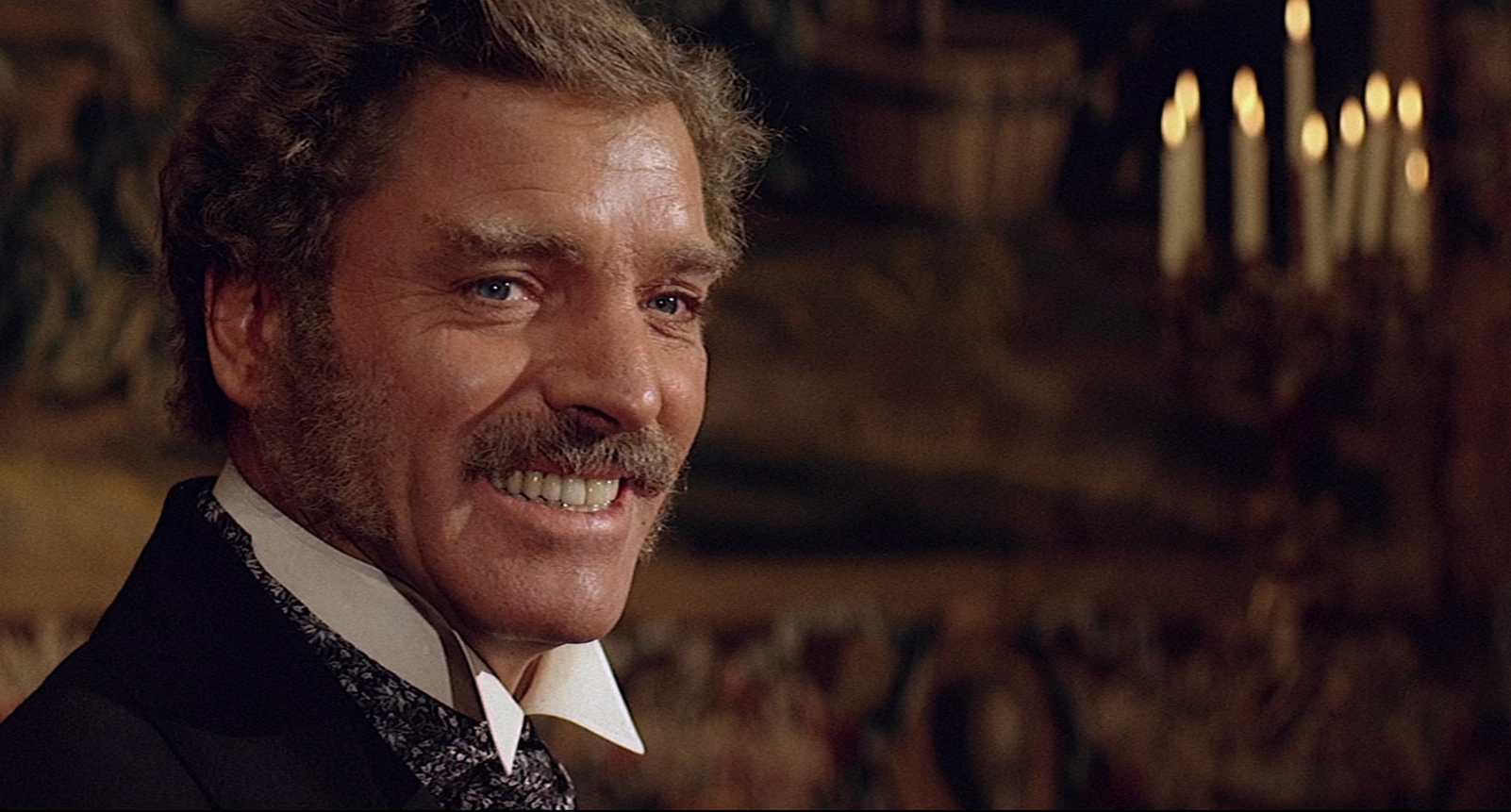

With the rugged features of a matinee idol and the physique of a trapeze artist, Burt Lancaster might easily have been typecast by Hollywood. Although he celebrated his physical grace and was not shy about appearing in action pictures, there was another side to his acting, right from the first: An angry, intellectual, introspective side, that led him to give some of the best performances of his generation.

From the earliest days of his career, while other stars were letting agents and studios guide their careers, Lancaster directed his own destiny; you could put together two film festivals, one of Lancaster as Hollywood star, the other of Lancaster as serious actor, and hardly believe you were looking at the same man. In some films, you’d see the laughing bravado. In others, you’d be reminded of Norman Mailer’s comment: “I’ve never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s.”

Lancaster died in his Los Angeles home Friday, at 80, of a heart attack. He had been ill for some time, following a stroke. “It’s the passing of a giant,” said Kirk Douglas, his co-star in six pictures. “But Burt will never die. We’ll always be able to see him swinging from a yardarm in ‘The Crimson Pirate,’ and shooting with me in ‘Gunfight at the O.K. Corral’.”

Yes, and we’ll also always be able to see him saying “Don’t touch the suit,” in “Atlantic City;” and coldly wrecking the lives of those around him in “The Sweet Smell of Success;” and finding freedom deep within himself in “The Birdman of Alcatraz;” and spending a long, sorrowful day of farewells in “The Swimmer;” and bringing a snakelike attractiveness to an Italian nobleman in “The Leopard.”

Few major stars of the last half century compiled such a distinguished and varied filmography. And when his career seemed on the wane in a Hollywood infatuated with young action heroes, he reinvented himself in Europe, working for directors like Luchino Visconti and Louis Malle.

Lancaster was born in New York in 1913, and was a college graduate who also trained and worked as a circus trapeze artist before making his first film, “The Killers,” in 1946. He became a star in a series of Hollywood crime pictures, some of them very good, like “Criss Cross” and “Sorry, Wrong Number,” both in 1948. And he became a box office force in “The Flame and the Arrow” (1950) and “The Crimson Pirate” (1952). He won an Academy Award for best actor in “Elmer Gantry” (1960).

I interviewed him in 1986, when he and Douglas were co-starring in the comedy Western “Tough Guys.” He was a man who said exactly what he thought, and when I mentioned that he’d been going in some new directions in the previous 10 years–meaning that as a compliment about such films as “Executive Action,” “Conversation Piece,” “Atlantic City” and “Local Hero,” his eyes narrowed.

“I started going in new directions back in 1953,” he told me. “That was when I went from ‘From Here to Eternity’ to ‘Come Back, Little Sheba.’ I always tried to do things that would expand me as an actor.You find out people don’t want you to do that. ‘Make another “Vera Cruz”,’ they say. ‘Make another picture like ‘Trapeze.’ Don’t do ‘The Leopard,’ for God’s sake’!”

“The Leopard” (1963), set 100 years earlier, had Lancaster as an aging nobleman alarmed by rapid changes in Italian society, and the rise of the Mafia. I asked him if his decision to go to Italy and work with Visconti, so soon after winning the Oscar, didn’t violate all conventional wisdom: Didn’t people advise him to stay at home and make big hits?

He looked pained at my question. “I’m sorry, my friend, but you’re talking through your hat. I bought 11 copies of ‘The Leopard’ because I thought it was a great novel. I gave it to everyone. But when I was asked to play in it, I said, no, that part’s for a real Italian. But, lo, the wheels of fortune turned. They wanted a Russian, but he was too old. They wanted Olivier, but he was too busy. When I was suggested, Visconti said, ‘Oh, no! A cowboy!’ But I had just finished ‘Judgment at Nuremberg,’ which he saw, and he needed $3 million which 20th Century-Fox would give them if they used an American star, and so the inevitable occurred. And it turned out to be a wonderful marriage. My best work.”

He paused. “But you see, nobody told me not to do it. I was the one who said I couldn’t do it.”

I got the point. At a time when few Hollywood stars could or would march to a different drummer, Burt Lancaster did it his way.