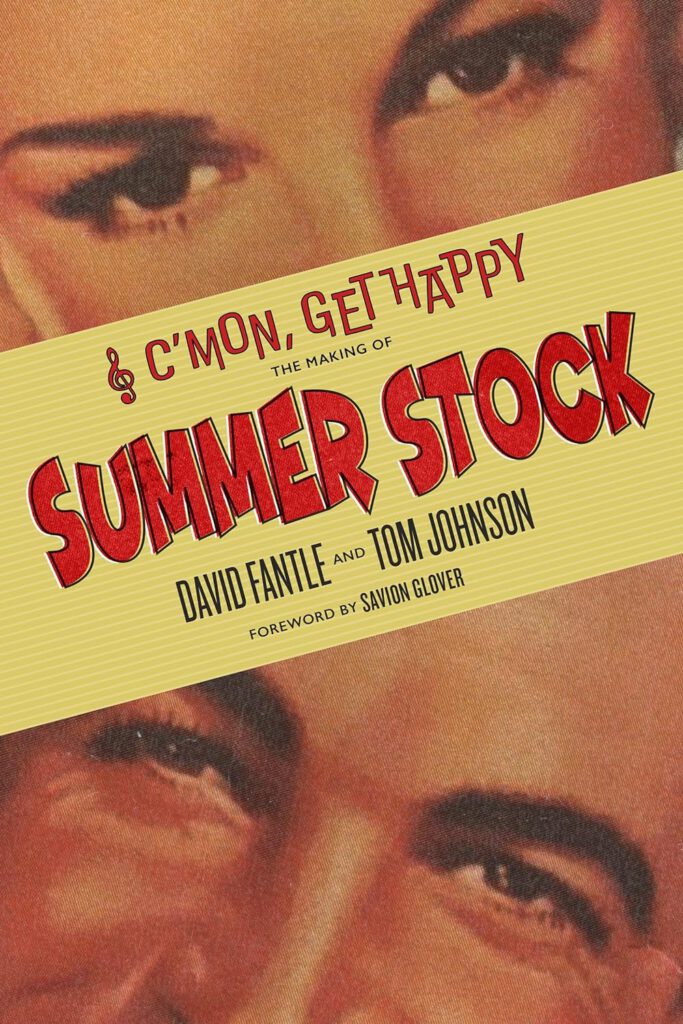

“Summer Stock” was Judy Garland‘s last film at MGM, the studio she’d worked for since she was 12. A new book, C’mon, Get Happy: The Making of Summer Stock, takes us behind the scenes, from the delightful (and likely exaggerated) saga of the original story pitch to the search for exactly the right paper for Gene Kelly to use in what he said was his all-time favorite solo number, the “floor squeak” and newspaper dance to “You Wonderful You.” In an interview, co-author David Fantle talks about the support Garland’s director and co-stars provided and what Hollywood’s censorship office found to complain about.

“Summer Stock” is probably most significant today for a few stand-out numbers by Judy Garland and Gene Kelly and an uneasy transitional piece at the end of the classic era of “Let’s Put on a Show” movie musicals. You use the term “maddening dichotomy.” What are the contrasting factors, and why is that maddening?

The dichotomy is that to the audience, “Summer Stock” is a characteristic “feel good” Joe Pasternak production and emblematic of the joyous song-and-dance musicals that were the MGM stock-in-trade, especially during the ’40s and ’50s. But in reality, getting the production to the screen was a long and, at times, tortuous process for many of the artists associated with the film, especially the director Charles Walters. Not every set is happy and fun – sort of akin to making sausage. The process isn’t pretty, but the end result can sure taste good.

What were some of the resources that were especially helpful in your research?

Researching the backstory of this film was challenging, especially during the pandemic when research facilities were not staffed and obtaining information was difficult. What worked to our benefit during this time was that many artists were idle and gave us time on Zoom or the phone to provide their “take” on various aspects of the film, including Savion Glover, Lorna Luft, Michael Feinstein, Tommy Tune, and so many others. We thought it was important to take a 73-year-old film and talk to “living” artists who can provide their contemporary take on the film and the artists associated with it.

One of the book’s wildest revelations is how the movie’s storyline was less developed than improvised. Can you tell us about how “the Mother of all pitches” happened?

Sy Gomberg was the principal screenwriter for “Summer Stock” with assistance from George Wells. We were able to find (thanks to Gomberg’s children) an article he wrote many years ago for a Writer’s Guild trade magazine on how he hatched and then sold the story to “Summer Stock” first to producer Joe Pasternak and all the way up the MGM ladder to Louis B. Mayer. It’s a great story, but we suspect with a bit of embellishment sprinkled in. We saw various script iterations, some containing a lot of over-the-top almost burlesque schtick, much intended for comic actor Phil Silvers. Fortunately, we believe, director Walters had the good sense (and taste) to excise some of those scenes.

I was glad to see you devote so much attention to director Charles Walters, generally overlooked in favor of Vincente Minnelli and Stanley Donen. What were the special strengths Walters brought to this film?

Charles Walter was the consummate company man known for bringing in his films under budget and on time. He certainly accomplished that with his first three directorial efforts, “Good News,” “Easter Parade,” and “The Barkleys of Broadway.” But his films, also including “Lili,” “The Tender Trap,” and “High Society,” were marked by good taste. Chuck started as a dancer and choreographer at MGM, so he learned the ropes before getting the reins of his first film, “Good News,” in 1947.

How did he work with the famously fragile Judy Garland on what would be her last film at the studio she’d worked at since she was a young girl?

Chuck danced and worked with Judy since 1942, including staging some dances for her in “Meet Me in St. Louis” in 1944. He was more than a director for her; he was a trusted friend. And as Judy’s insecurities mounted, she needed, especially in “Summer Stock,” the “security blanket” of Walters, Kelly, Bracken, Silvers, and DeHaven, all people she loved and trusted to get her over the finish line.

What did he say to her about the iconic “Get Happy” number?

To motivate Judy and get her in the right frame of mind, he told her to channel the great singer Lena Horne. So in “Get Happy,” thanks to Walters, Lena served as her motivation.

Today’s audiences will be either horrified or amused by the notes the production received from Hollywood production code enforcer (censor) Joseph Breen. How did you uncover his memo, and how did the memo affect the production?

The Academy Library in Los Angeles has all the Breen Office files on film productions they “approved.” “Summer Stock” was no exception. We were able to review these files. By all measures, “Summer Stock” was a wholesome production, but even Breen and his staff nit-picked on a few items: the hem of a dress, the passion of a kiss, the use of certain song lyrics, etc.

The “Dig, Dig, Dig for your Dinner” number has some very impressive tap dancing, but by today’s standards, its revivalist theme seems odd. How did the film’s original viewers respond?

Like so many Gene Kelly solos, we imagine it generated applause when it first screened. From personal experience seeing the movie many times, including recently, the number still receives applause as it shows how Kelly can brilliantly dance in such confined spaces. What doesn’t play as well is Phil Silvers’ “revivalist” schtick that precedes the actual dance and does seem dated.

One of the most surprising details in the book is the search for just the right paper in the squeaky board/newspaper dance. What did you discover, and how did you learn about it?

We were able to find secondary research that recounted the nearly impossible task of finding the right newspaper that could be cured and precisely torn by Kelly during the filming of the number. Fortunately, we were able to talk with Kelly’s daughter Kerry and Nick Castle Jr, the son of “Summer Stock” choreographer Nick Castle, who were able to provide us with first-hand information on how the number was devised based on their recollections. It was Kelly’s favorite film solo, and as choreographer Mandy Moore says in our book, the number is purely “cinematic,” it could have never been done in a live theater performance.

When was the first time you saw the film, and how has your view of it changed on repeat viewings?

We first saw the film in the summer of 1978 at the Vagabond Theater on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles in its original 35mm format. We were 18 and flew to Los Angeles from our homes in St. Paul, MN, for our transformational meetings with Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire that fueled our passion for Golden Age films. Our impression has not changed much through the years: the plot didn’t break new ground, but the quality and quantity of the musical numbers crammed into 108 minutes make the film joyous and enduringly entertaining. And as Judy’s swan song at MGM after 15 years, we felt the story was due for a book.