“I’m going to make the movie regardless of whether you want to or not,” Clint Eastwood told the suits at Warner Bros., when they balked at financing “Million Dollar Baby.” They’d read the screenplay, Eastwood recalls, and they said “we don’t think boxing movies are very popular right now.” You can imagine Eastwood’s eyes narrowing as he responded, “This to me is not a boxing movie. It’s about hopes and dreams, and a love story.”

His agent shopped the project in three or four places, Eastwood told me. “They all passed. Then Tom Rosenberg in Chicago, of Lake Shore Entertainment, called up and said he was bullish on the film, he wanted to finance half of it and take the foreign rights. I didn’t know Tom that well, but he understood the film.”

With half the money on board, Eastwood said, “Warners finally called up and said, ‘You’ve been here a long time, so we’ll finance the other half’.”

He has been there a long time. Twenty-five years, on and off, making millions for the studio as a star and director. “I can’t promise you you’ll make a zillion dollars, like on one of your sequels or remakes,” Eastwood told them, “but if everything goes well, I think it’ll be a film you’ll be proud to have your name on.”

Well, it’s that all right. In a season of enormous publicity campaigns, “Million Dollar Baby” was almost a stealth opening. It was screened for critics. They liked it so much, “people are leaving the screenings stunned,” wrote industry pundit David Poland. The film took on a life of its own, shouldering its way into the front of the Oscar ranks just on word of mouth. It opened Wednesday in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, and will open widely after the first of the year.

Eastwood said he took a low-key approach in preparing the movie. “I just wanted to make it. I don’t want publicists hanging about. We stayed under the radar. With all the big $150, $200 million films out there, they thought this film was at a different importance level. I had about $25 million to make it with. They had their ‘Alexanders’ and ‘Polar Expresses’ they were working on, and I figured my movie was going to have to live or die on its own terms.

“So, we went and made it, they didn’t know anything about it, and after we showed it to them,” Eastwood recalled, “they said, ‘Jesus, it’s not too bad.’ Some people in the organization started getting enthusiastic. Eddie Feldman, the distribution guy, says, ‘How shall we open it?’

“‘Why don’t we just put it out sometime after Thanksgiving,’ I said. He said we had to mount a campaign. ‘No mounting a campaign, no mounting anything,’ I said. ‘Just see where it goes.'”

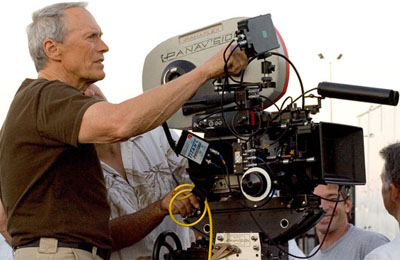

Eastwood was speaking by phone from Los Angeles, where, at 74 and fresh from last year’s success with “Mystic River,” he’s at the top of his game.

“If boxing movies weren’t supposed to be popular, I asked, what were? Sword and sandal movies? Bill Goldman, the writer, was right when he said: ‘Nobody knows nothin’.’

“At the major studios, you see people wanting to remake a TV series, wanting to make a sequel. I guess I’ve done it in my career, three different sets of sequels, but I’m too old for that now. I kind of try to advocate that maybe they should just concentrate on writers and original scripts and go back like the old days and have writers in the building …

“I made this movie for the story and the relationships. No computer special effects, nothing to slow things down. We shot it in 39 days, the same as ‘Mystic River.’ When I look back at the pictures I grew up on, like ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ — it was made in 39 days. Everybody accuses me of moving fast when I direct a picture. I don’t move fast, but I just keep moving. I come to work ready to make films. I love it. I’ve been doing it a long time, and every time I think I’ll quit, something good comes along.”