Toronto, Ontario – It went like this.

I asked John Malkovich about his suddenly booming career, and he quoted Edward Albee: “Careers have been responsible for the destruction of more artists than anything else.”

I asked him about appearing in a movie that may win him an Academy Award nomination, and he said he is addicted to bad movies, and will go to three a day. He remembered the fun he had watching “The Lonely Lady,” with Pia Zadora “talking, so to speak, her way to the top.”

I asked him how he prepares to play a new character, and he says he never does a lot of research.

“I’m not a Method actor. I don’t believe acting should be psychodrama. I look within myself and see what I can find to play the role with. If I’m playing a blind man, I don’t go around blindfolded for days. A lot of good actors would, but I don’t go in for that very much. I like to just make it up as I go along.”

I asked him about his roots in Chicago theater, and he said, “In Chicago, nobody gives two f—s about you, which is one of the things I like about it. I spent six or seven years there pulling in six grand a year, and I had a wonderful time. I love Chicago, but in a lot of ways it’s a disappointment. You can work there for years and years, and because you’re in Chicago, you don’t get the recognition. It has some of the best theater in the country, but when they shoot a movie there they bring in all their actors.”

Malkovich is not being contrary, and he is not being controversial. He is just saying what anybody else would say if he had not yet been programmed as a media creature. He has not yet been programmed. He sits in the suite they have rented for him in Toronto, the day after the premiere of his new movie, “Places in the Heart,” and he lights a Camel filter. And when I ask him how he feels about the fact that he is becoming a brand name, “Malkovich,” and that the brand is beginning to take on some of the same associations as Brando, Hoffman, and De Niro had when they were new to the movies, he blows out the smoke in a long, weary sigh and he says:

“I don’t mean this arrogantly or modestly, but people have been saying that about me for a long time, and the evidence of it is personally lost on me. I just don’t see it. I’ll never be the biggest kind of star, I’ll be like Bob Duvall, respected as an actor but a lot of people can’t identify the face. I don’t have the personality of a big star, or the looks of a Mel Gibson or a Paul Newman, or the style of a George C. Scott.”

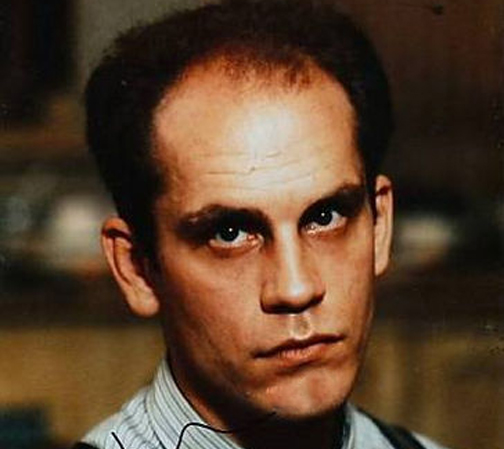

And so what does he have, then? John Malkovich, who is said to be the best young actor coming up right now, is slender and balding, and he speaks so softly that he could sometimes be musing to himself. He looks… well, look at his picture. How would you describe him? The comparison with Duvall is interesting, because they both have the high foreheads and the deep eyes and something else, a certain strength of character in their faces, so that you do not think you could get them to look blank – there’d be too much going on inside.

And then look at “Places in the Heart,” his first film. Malkovich plays a proud, angry blind man who comes to board with Sally Field on the Texas cotton farm she is trying to keep out of the hands of the bank. His role denies him the actor’s greatest tool, the eyes. He uses them anyway. Unlike many actors who would affect a blank stare when playing a blind man, Malkovich, who says he does not study for his roles and works from what he finds inside, adopts an unusual approach and uses his eyes. They shift back and forth, not quite looking where they should be looking, but looking close enough that you can sense his character’s refusal to completely accept the fact that he is blind. This is a man who at some level is still pretending he can see.

And Malkovich makes another interesting choice: Although his character has been blind for many years, he still works his way around rooms with a great deal of reaching out and touching and fumbling for familiar landmarks. When he puts a record on his phonograph, it’s touch and go whether he’ll drop it. Another actor might have played the character as a blind man who prides himself on knowing exactly where everything is, never having to be told. Although Malkovich’s performance feels right, and there is a presence about him that causes you, curiously, to look at him more than is strictly necessary in any given shot, it takes a moment’s reflection to understand his approach to the character. This is a parody of a blind man, and the parodist is not Malkovich but Mr. Will, the character himself, who says with his actions that although he must be blind, he does not therefore feel obligated to make things as easy as he can for other people.

The performance is being talked about, even in a movie filled with other good actors and good performances. This is Malkovich’s year, and they are talking about other performances, too. Later this year, he will appear in another movie, “The Killing Fields,” playing an American freelance photographer in Vietnam. Right now he is back on Broadway with Dustin Hoffman in “Death of a Salesman.” He is the director of the Steppenwolf Theater Company’s production of “Balm in Gilead,” which just opened Off-Broadway to strong reviews. Early next year, he will return to Chicago to direct a new play at Steppenwolf named “Coyote Ugly.” His next film will be “Eleni,” directed by Peter (“The Dresser”) Yates, the story of a Greek-American New York Times reporter who discovers why and how his mother was tortured and executed after World War II.

In “Death of a Salesman,” Malkovich made some interesting choices in playing Biff, the son who is Willy Loman’s great failure. Biff has often been played in the past as an all-American bluff, a healthy, strapping kid with terrible things in store for him. Malkovich played Biff as older, wiser, dreamier and more detached than is usually the case. Willy is still playing the game, but in some sense Biff has already left the field. He is sometimes not there with Willy, but observing him, detached, curious that this person could still contain hopes for which Biff no longer, has the energy.

All of this began for Malkovich because of an old girlfriend. He did not necessarily set out to be an actor at all. He grew up in Downstate Benton, “which is not a cultural mecca,” he said, “I played football… sports and stuff… and in college I studied environmental things. My father was the state director of conservation. But my girlfriend was in theater, and so I drifted into theater because of her. That was about how it happened. It’s very odd, because, you know, I felt there were two or three things I could have done rather well, so it was very chancy to get into theater.”

I asked him if he’d been the kind of child who drew attention to himself.

“I was a bit of a class clown, but I wouldn’t call it a performance mode. A lot of people who knew me well were very surprised to see me on a stage.”

After school, he came to Chicago and was one of the founders of the Steppenwolf company, at a time when there was great opportunity in Chicago theater, and no money. The company members formed a sort of commune. They acted together, built sets, sold tickets, decided which plays to present, moved from theater to theater, and broke off, from time to time, into various combinations of couples.

From those days, Malkovich says what he misses most are the small theaters. “We didn’t need larger ones. For all that you hear these days about Steppenwolf, it might surprise people to learn that over a period of seven years we played to an average of 57 percent capacity, which is a little beyond absurd. Nobody really cared about what we did, which freed us to do whatever we wanted.

“In Highland Park, I remember, we played in a theater with 88 seats. It was smaller than this hotel room. When I opened in Chicago with Dustin in ‘Salesman,’ I was completely lost in a big house. I was used to playing in closeup, using my face a lot. In the early weeks of ‘Salesman,’ I’d be performing these deep feelings in what I took to be an unnaturally loud voice, and the director would come backstage and tell me, ‘Excuse me, but there are people paying $35 a head out there tonight, and they would like to be able to hear you.’ Not until the very end did I feel more or less in charge of what I was doing.”

Steppenwolf spent six or seven years putting on six plays a year, fiercely committed to Chicago. Then its production of Sam Shepard’s “True West” became a big hit, after having already flopped in New York, and Malkovich and Gary Sinise were asked to take it to New York. The company was split between those who saw that as selling out and those who, like Malkovich, wanted to retain a Chicago base while still taking the opportunity to get wider exposure in New York. Malkovich went. But recently he held a press conference to announce that Steppenwolf was staying in Chicago, that he would be back to direct, and that he planned to continue acting in Chicago.

“All I really hope,” he said, “is that some of this attention will get us some more support in Chicago, by which I mean corporate underwriting. Everybody’s lined up to give to the Lyric and the symphony, but what induces theater to stay if there is no sign of support? Ticket sales alone aren’t enough.

“Still, it’s a lot easier to produce good theater in Chicago than in many other places. I know for a fact that a lot of actors are desperate and unhappy if their careers are not progressing at what they think is the correct rate. They just go crazy if they’re not working. I don’t feel I’d be that way. You can always get a few people together and put on a play. Maybe not in New York or L.A., but in a lot of other towns, you can.”