Sid Vicious was angry most of the time about something, but this night he was particularly mad because he was a f – – -ing rock ‘n’ roll star and Malcolm McLaren had him on rations of eight pounds a week — about $14. We were in Russ Meyer‘s rented car, driving down the Cromwell Road in London, and Vicious told Meyer to pull over in front of a late-night grocery so he could lay in some provisions.

Meyer and I watched as he skulked into the store, wearing leather pants and a torn T-shirt and big, black Doc Martens, a brand of shoe favored by London’s punks because they were ideal for kicking people. Vicious’ hair was spiky and his eyes were bloodshot. Through the window we could see the store owner exchange an uneasy glance with his partner before Sid pulled up at the checkout counter with his supper, which consisted of two six-packs of beer and a big can of pork and beans. A few minutes later, we dropped Sid off in front of the place he was living, an anonymous brick building on an anonymous brick road, and then we drove back toward the flat we were staying in, down near Cheyne Walk, near the Thames. It was the last time I would ever see Sid Vicious, but God knows it would not be the last time I would ever hear about him.

We had been working together on a movie about the Sex Pistols, a movie that would never be made. In the years to come, the Pistols would disband, and Vicious would sink into a hell of drug addiction; still ahead of him were an arrest on the charge of stabbing his girlfriend to death, and his own death by a heroin overdose. He was still a teenager when he died, and now that his brief life has become a footnote to cultural history, it has inspired a brilliant new movie, “Sid and Nancy,” the best movie ever made about sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, and the most relentless and despairing.

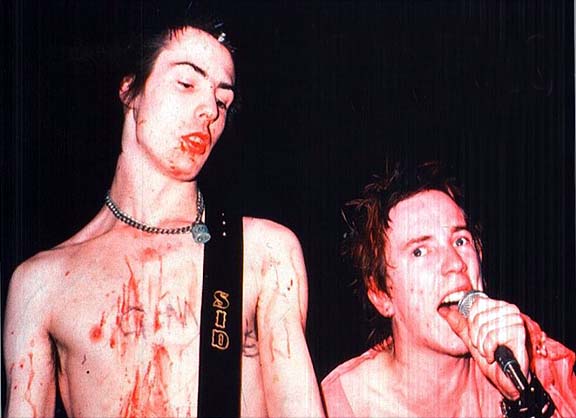

But all of that is another story. Meyer and I were in London to work on a project that seemed wildly unlikely to both of us. He was the director and I was the writer of a film first titled “Anarchy in the U.K.” and later “Who Killed Bambi?” It would star the Sex Pistols, a punk rock band that had grown notorious for its blend of anarchic music, scabrous dress, offensive behavior and violent fans. We had been hired by Malcolm McLaren, a breezy London promoter who had created the Sex Pistols more or less out of his own imagination, although after he discovered lead singer Johnny Rotten and guitar player Sid Vicious the band took on a very real life of its own. (The two other members of the band, Steve Jones and Paul Cook, seemed to be along for the ride.)

This was the summer of 1977. In late June of that year, I received a call from Meyer, a legendary Hollywood filmmaker who specializes in stylish action pictures featuring cartoon sex, redneck heroes and bucolic heroines in demolition derbies for the emotions. His formula: big bosoms and square jaws. Several years earlier, in 1969, I had written the screenplay for Meyer’s “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls,” a 20th Century-Fox production that made a lot of money when it was released, and then went on to gain cult status among the midnight movie fans of Europe.

Apparently, Meyer explained, the Sex Pistols were among those fans. He had received a call from McLaren, then riding high as the manager of the hottest media phenomenon in Great Britain, explaining that he, Rotten, Vicious and other members of the London punk world made regular visits to the Electric Cinema on Portobello Road, where “Beyond the Valley” played at midnight on weekends. A satirical sage of the rise and fall of a female rock group, it had become their favorite movie, and now they wanted Meyer to direct them in their own film. Meyer asked me if I wanted to return as screenwriter.

“What sort of picture will it be?” I asked.

“McLaren says he wants to do the flip side of ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls‘,” Meyer said.

“But ‘Beyond’ itself was the flip side of ‘Valley of the Dolls,’ ” I said.

“You figure it out,” Meyer said. “McLaren is flying out here to Los Angeles next week.”

The offer sounded like one of those life experiences you don’t want to miss, and so I signed on and, a week later, met with Meyer and McLaren. I established headquarters at the Sunset Marquis, a hotel much frequented by music and movie types, and Meyer hauled in card tables, typewriters and yellow legal pads.

McLaren briefed us on the Pistols. He had an armload of press clippings, describing the Pistols being thrown out of clubs, attacked by fans, arrested in front of Buckingham Palace, and saying rude things on the BBC. Then we looked at videotapes of the Pistols on TV and in concert. We listened to all of their records. And McLaren talked and talked and talked.

As he talked, I speculated that McLaren himself would make a good subject for a movie. He was a literate, educated Londoner, of average appearance except for the “bondage pants” he wore — leather pants festooned with straps and buckles, so that, presumably, he could be rendered immobile at the drop of a whip. The pants were a best-selling item at Sex, the punk boutique that McLaren ran on London’s Kings Road — which was then the stomping ground of the punks.

Despite his pants, McLaren was all business, and the only action the buckles and straps saw was when we ate in restaurants; he would invariably get his restraints tangled around his chair legs, and overturn chairs and tables as he stood up to leave the restaurant.

McLaren’s notion was that the Sex Pistols stood for the total rejection of modern British society, and especially of the millionaire rock establish symbolized by Mick Jagger. “These guys are all in their 30s and drive around in Rolls-Royces,” McLaren said. “What do they have in common with the typical 16-year-old London school-leaver who has no job, no money, no prospects and no hope?” The Sex Pistols music spoke for these disenfranchised, he said, and the movie should be a statement of anarchic revolt against the rock millionaires, and the whole British establishment.

We went to work. Within a week, I had a rough treatment ready. It opened with an unemployment line, continued with the Sex Pistols trying to play their music in a strip club while the customers shouted for the girls, and included a scene in which a millionaire rock star leaped from his chauffeured Rolls to shoot a deer with a bow and arrow. He was witnessed committing this act by a young girl who would reappear at the end of the film to assassinate the star and shout the immortal line, “That’s for Bambi!”

McLaren supplied situations and dialogue advice. Here are some sample dialogue passages from the original screenplay (which has become a collector’s item and goes for $50 at movie memorabilia stores):

Rotten: Got a problem and the problem is you.

Jones: We don’t make music — we make noise.

Vicious: There are too many stars as it is.

Rotten: It’s more fun being on the dole.

Vicious: Rock and roll? What’s that? We was happier on the streets!

And so on (most of the dialogue is unprintable). The action includes such passages as Vicious fighting a dog named Ringo, and Johnny Rotten demolishing on a street-corner Scientology testing center. The plot involves a scheme to overthrow the rock establishment, and Johnny Rotten utters the euglogy over the fallen body of the rock millionaire:

Rotten: Did yer ever have the feelin’ yer bein’ watched?

After we finished two drafts of the screenplay in Los Angeles, Meyer and I flew to London, where we met the Sex Pistols themselves. McLaren’s idea was that they would go over their dialogue with us, making suggestions. I assumed they would reject everything I had written, but they affected a total disinterest in the screenplay; their literary contributions were limited to penciling in “f – – -” every three words.

Cook and Jones were hardly seen during the days we spent in London. McLaren came to the flat every day, and took a lively interest in the process of auditioning possible actors for the movie. (Among the actors cast were Marianne Faithful, who would play Vicious’s mother, and fallen rock idol P. J. Proby, who would more or less play himself.) When Rotten and Vicious came by, it was mostly to ask McLaren for money, although I remember one immortal exchange between Russ Meyer and Rotten:

Rotten: “F – – – off, you sod.”

Meyer: “Listen, you. We fought the Battle of Britain for you, and I’m ready to fight it all over again and whip your ass.” Apparently impressed, Rotten retired into silence, unaware that (a) America did not fight in the Battle of Britain, and (b) as an Irishman, he or his forebears were officially neutral, anyway.

One day McLaren, Rotten, Meyer and myself went out for lunch. Rotten seemed to enjoy intimidating waiters by playing dumb and asking the same questions over and over again, until Meyer lost patience and ordered for him. If “Who Killed Bambi?” had ever been made, I imagine there would have been open warfare between the two of them, because Meyer was emphatically unimpressed by Rotten’s aggressive rudeness. But this day, mellowed by beer, Rotten relaxed and even showed some glimmers of the person he would eventually metamorphose into — John Lydon (his real name), leader of Public Image Ltd., a neo-punk band who believes music is at least as important as the musician’s personality defects.

We were talking about Sid Vicious, and Rotten observed that Sid had become like a new man since he had fallen in love. I do not know if the woman Sid had fallen for was Nancy Spungen, the heroine of “Sid and Nancy,” but I assume so. I remember Rotten observing with wonderment that romance had inspired Sid to clean up his act: “He even changed his underwear for the first time in two years.”

“I don’t believe it!” said McLaren. “Did you actually see him taking it off?”

“He didn’t take it off,” Rotten said. “He had been wearing it too long for that. He had to shave it off.”