[A reconstructed version of Samuel Fuller‘s “The Big Red One” is going into release around the country, and will soon be on DVD. Roger Ebert talked to the legendary director at Cannes 1980.]

Sam Fuller is the kind of guy who, when he walks into your living room, looks around for a place to sit down and sits on your television set.

That was what he did the last time I saw him, which was 10 years ago. He was visiting Chicago as a living legend on tour. Fuller became known in the 1950s as the hard-boiled director of some of the best B pictures out of Hollywood.

His credits included such titles as “The Steel Helmet,” “Pickup on South Street” and “Underworld USA.” In 1966 he made “The Naked Kiss,” and in 1967 something called “Shark,” but by 1970 be was out of work — “between projects,” they call it in Hollywood.

He was in Chicago to talk to a film society, and he wound up in my living room, sitting on the TV, sprinkling cigar ashes on the floor, talking to half a dozen film buffs until 3 in the morning about the big project he was working on. It was going to be based on his experiences in World War II, and it was called “The Big Red One.”

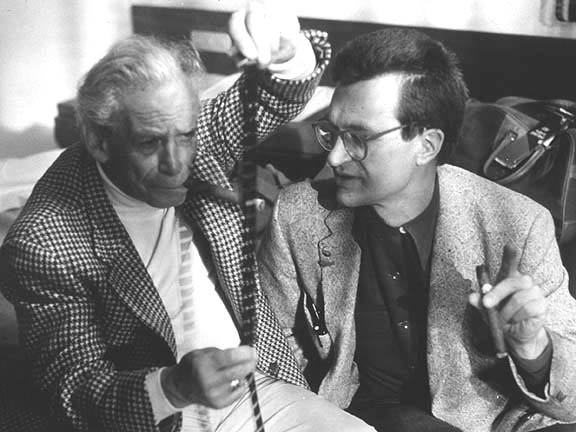

Now it was 1980 and Sam Fuller was sitting in a chair just like everybody else, still shedding cigar ashes in every direction – but it wasn’t Chicago this time, it was the Cannes Film Festival, and Fuller wasn’t there as a cult hero but as the director of a film in competition. The film starred Lee Marvin, it was about a bunch of infantry soldiers in World War II, and it was still called “The Big Red One.”

“It took a little time to get off the ground,” Fuller explained.

He is a wiry, steel-haired little guy with a tough way of talking. Maybe he was born talking that way, or maybe he picked it up back in the ’20s, when be was a teenager lying about his age and breaking in as a New York crime reporter. He had worked his way up to pulp writer by the, time World War II broke out, and he fought all the way through the war. He also sold a gangster novel that he wrote while he was in uniform, and that scene’s in the movie: The kid getting a publisher’s acceptance letter in the middle of a battlefield.

“The movie is maybe 20 percent my story,” he said. “But the character based on me, played by Bobby Carradine, isn’t nearly as vicious as I really was. The other 80 percent is a composite of dogfaces I knew, fought beside, witnessed, heard about or dreamed up.

“Lee Marvin was terrific to work with, playing the sergeant. He wanted to make the movie from the moment he heard about it. I love the son of a bitch…even though he was a marine. Some of my best friends were marines. But this isn’t a story about the Marines. It’s a story about the infantry. You can tell the difference because the Marines took islands, whereas we took continents.”

When Fuller talks, he doesn’t pause for the laughs, as if he’s doing material. He talks, gravel-voiced, as if he’s explaining things very patiently to people who have seen a fraction of his experience, who are perhaps soft-boiled instead of hard, but who are probably all right guys if he got to know them.

Fuller, who is a hero among European movie directors, has been cast in movies by Jean-Luc Godard (“Pierrot le Fou“) and Wim Wenders (“The American Friend“). He played himself in one and a gangster in the other. It was the same performance.

He ordered a Bloody Mary and lit another cigar and assessed his chances of winning a big prize in the Cannes Film Festival. He thought they were pretty slim, and it would turn out that he was right.

“Kurosawa he’s a landslide,” Fuller said, correctly predicting that the great Japanese director would win the grand prize. “The other big prize, that’ll go to Resnais.” He was right again.

“The thing about these festivals that bugs me,” he said, “is the goddamned subtitles. I hate those titles. You break your ass on a scene, and maybe the most important thing in it is the look in the girl’s eyes when she’s looking at the guy. So where is everybody looking? Down at the subtitle, where she’s saying, ‘I love you’ except everybody already knew that was what she was saying, but if you leave it out, they think they’re missing something.

“I was in Germany, I saw ‘Rio Bravo’ with John Wayne and Dean Martin. Well, of course it was all done tongue-in-cheek. I laughed my ass off. The Germans sat there seriously. Due to the lousy subtitles, they thought it was a serious movie. I used to say they ought to put in the subtitles to let people know when it’s a joke.

“Thank God my movie isn’t an O’Neill play. You know: everybody talking, standing up, talking, going to the window, talking, and then they leave, still talking. The subtitles would drive you out of the room. But with a movie like ‘The Big Red One,’ when a guy has his ass hit by flying fragments, you get the message. And I worked with British special effects guys on this movie, so we got great flying shrapnel. In the U.S., it’s against the law to use TNT or dynamite for your explosions in a movie. We shot in Israel, where they never heard of that law.”

Fuller was hitting his stride, holding court. His original audience of one had been enlarged by the addition of a West German television crew, and his words and gestures expanded to fill the wider circle. One of the Germans asked him if “The Big Red One” was pro-war or anti-war.

“Pro or anti, what the hell difference does it make to the guy who gets his ass shot off? The movie is very simple. It’s a series of combat experiences, and the times of waiting in between. Lee Marvin plays a carpenter of death. The sergeants of this world have been dealing death to young men for 10,000 years. He’s a symbol of all those years and all those sergeants, no matter what their names were or what they called their rank in other languages. That’s why he has no name in the movie.

“The movie deals with death in a way that might be unfamiliar to people who know nothing of war except what they learned in war movies. I believe that fear doesn’t delay death, and so it is fruitless. A guy is hit. So, he’s hit. That’s that. I don’t cry because that guy over there got hit. I cry because I’m gonna get hit next. All that phony heroism is a bunch of baloney when they’re shooting at you. But you have to be honest with a corpse, and that is the emotion that the movie shows rubbing off on four young men.”

Fuller was weaving the spell of his movie’s story now, almost as if we hadn’t seen it, as if it were a project he wanted to sell to us.

“I wanted to do the story of a survivor, because all war stories are told by survivors. Pro- or anti-war, that’s immaterial, because in any war picture, you’re going to allegedly feel anti-war because they make a character sympathetic and then the character gets shot, and so you say, ‘How tragic.’ What baloney. Why should I be against war because some kid gets hit while he’s reading a letter from Mom? I don’t think I’ve seen any war movies where you get to know the characters and one of them isn’t killed. It’s a cliché.

“But to the guy who’s killed, try telling him about heroism and courage. Get him to listen after he’s dead. Even World War II, with all its idealism, basically there was a lot of hypocrisy. Because basically what the rich were saying was, ‘We loaned a lot of money to Europe that we’re never going to get back if Hitler wins.’ That was a valid enough reason for fighting the war.

“But what was sad was that they waved the flag and let the band play for a bunch of young men to go fight the war, and never gave them a piece of the corporation called the country. And Korea, they called that one a police action, to which the bone-weary dogface replied, ‘Fine! Send in the cops!’ Now, with Vietnam, we have all these euphemisms to tiptoe around the fact that we lost.”

The German TV guys said maybe it would be best to shoot outside, in the sunlight. Fuller stubbed out his cigar and drained his Bloody Mary and sighed and said, “Still, maybe we were all lucky to fight when we did. In the old days, if you came to the king and told him the battle was lost, you got beheaded. If I had been the guy who had to break the bad news to Tamburlaine, I woulda gone in and said, ‘Uh…I’m terribly sorry, sir, and I don’t want to get into the details…'”

Fuller grinned. “Then there was the dogface who picked up the walkie-talkie and got hooked up with the general and said, ‘Hello, we lost.’ And hung up.”