Bio-docs have become a staple of the film festival circuit, an easy way to get butts in seats by attracting fans of the subjects on the screen. To be honest, this genre of non-fiction filmmaking has also become glutted with lazy artistry, putting cameras down in front of interview subjects and asking them to tell stories about themselves, or, worse, anecdotes about famous people they know. They’re usually shallow renderings of what made these people successful enough to have a movie about them in the first place, and all three of the bio-docs in this dispatch fall into this trap a few times, but the best of the trio elevates its subject by highlighting not just his game-changing abilities but his deep empathy for the human condition.

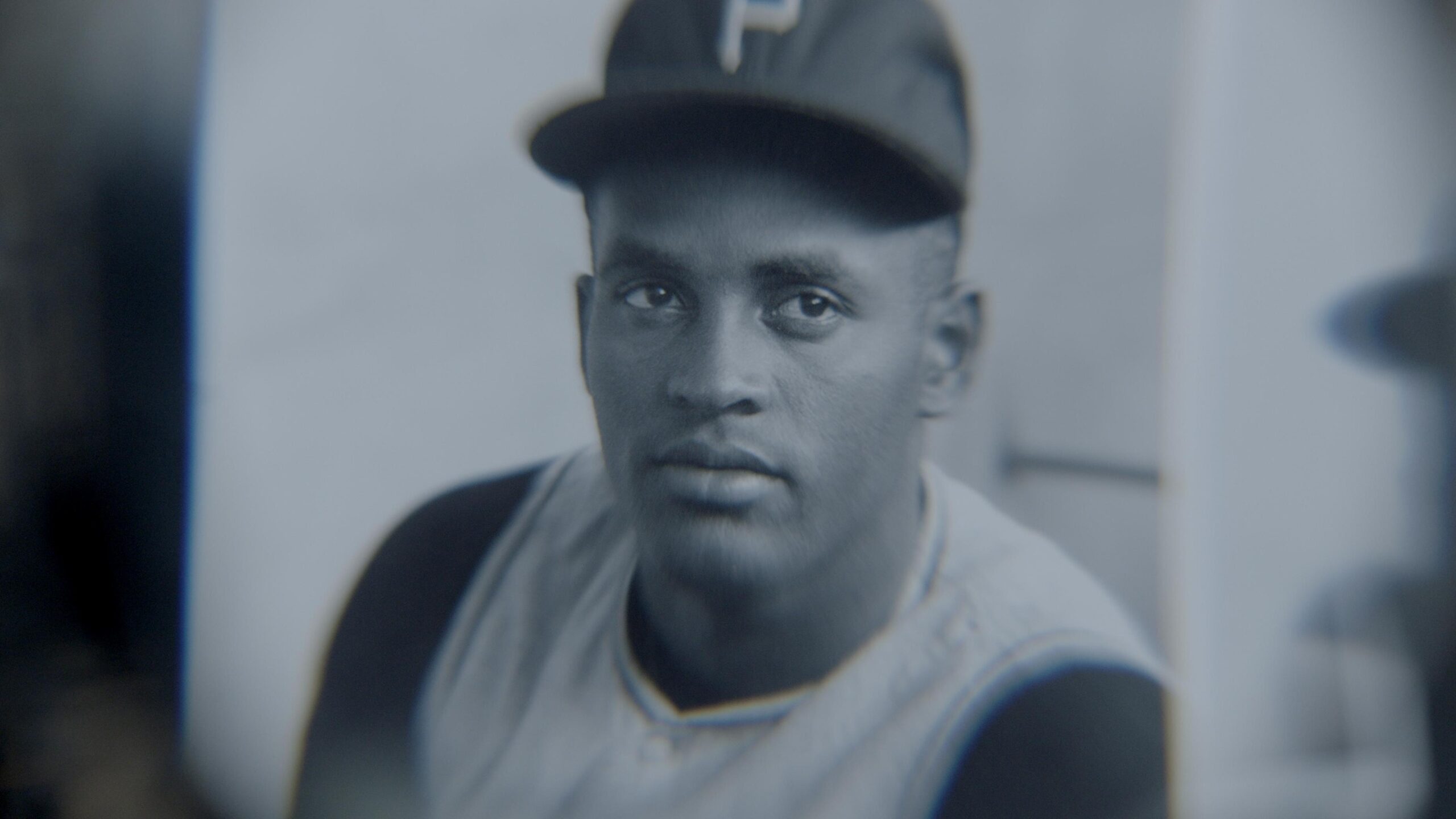

That film is David Altrogge’s “Clemente,” a loving ode to one of the most impressive and important athletes of all time. Robert Clemente was the first Latin-American to win an MVP, a World Series MVP, and be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He shattered the color barrier in a way that still resonates across all sports to this day. It was kind of perfectly appropriate to watch this movie on the same day I was downloading the latest edition of Sony’s “The Show,” which has on its cover the great Vladimir Guerrero Jr., one of many Latin-American athletes following in Clemente’s giant footsteps, and continuing his legacy in the way they’re changing the game.

“Clemente” spends enough time on the field and in the clubhouse for baseball nuts, focusing a great deal of time on the historic 1971 World Series, the one in which Clemente’s Pirates came back down two games against one of the most impressive teams of all time in the ’71 Baltimore Orioles. That he would be dead just over a year later, perished in a plane crash while trying to take emergency supplies to Nicaragua, was unimaginable to his millions of fans.

The baseball stuff is fun-but-familiar—it’s in the humanizing of Clemente that Altrogge’s film really succeeds. Not only does he get warm interviews from Clemente’s sons, he speaks to the fans that Roberto interacted with in ways they’ll forget. There’s an amazing story from a woman whose father drove Clemente after the team left him because he was taking too long signing autographs—their families became friends for life. Richard Linklater, who also produced the film, shares how he used to send photos to his favorite athletes in the hope of getting a signature. Clemente wrote back. He would just show up at children’s hospitals because he knew his presence could do some good. One might say “Clemente” is a piece of hagiography, but it feels like this is a guy who deserves it. As someone says in the film, “Everything about him was royalty.” Let him wear the crown placed on his head by the movie that bears his name.

There are no crowns being handed out in David Bushell’s “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie,” a detailed history of the early lives and partnership of two of the most famous comedians of their generation: Tommy Chong and Cheech Marin. Both gentlemen come off splendidly, particularly in a series of conversational scenes as they drive through a desert talking about their friendship and sometimes-contentious partnership. There are times when some of these scenes feel a bit stagey, especially as the pair gets into fights about their eventual break-up, and I longed for a bit more context about Cheech & Chong’s impact on comedy—ethnicity is oddly avoided for most of the project, which is a mistake given how many doors these guys opened and how their unique, cultural voice is one of the reasons they became so popular. Having said that, this is certainly an easy watch, the kind of thing that I suspect will pop on a service like Hulu later this year.

To this viewer who knew little about the backgrounds of Cheech and Chong, the early biographical material is enlightening, especially in regard to the very different life that Tommy lived as a musician long before he met Marin. It turned out the pair were drawn together by a love for improvised comedy, admiring those who could develop charact3rs and bits on stage, and aware that they could do the same. I wished that “Last Movie” simply had more comedy material in it—the balance is sometimes off between how Cheech & Chong got famous when the film could have used a little more why.

It’s also a bit unusual that “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie” basically ends with their break-up. The details about how that happened—Marin accuses Chong of being a bit too power-hungry as a director while Chong seems honestly betrayed over being asked to do little more than a cameo in “Born in East L.A.”—is some of the most interesting material in the film, but, again, I wanted greater context. How did the guys get out of the shadow of what were actually characters they were playing—even though so many though these two guys were just version of the people playing them? And everyone knows how Chong has struggled with legal issues around something that’s now widely legal. They were ahead of their time in SO many ways, comedically and culturally, which makes the fact that “Last Movie” feels stuck in the ‘70s and ‘80s all the more disappointing.

There’s a similar lack of ambition in “This is a Film About The Black Keys,” a project that will likely play well for fans of the Grammy-winning rock duo but will struggle to bring anyone new into that fan club. Jeff Dupre’s film has a “Behind the Music” quality to it in how it hits all the major career checkpoints in the careers of Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney from their lives growing up in Akron to being one of the most popular bands in the world. The brutal truth here is that, while Auerbach and Carney are undeniably talented, there’s not much meat on the bones of their life story. It’s nice to see two dudes who are so good at what they do find fame, but that’s about it here, other than another case study in how two-man bands are going to inherently struggle when there’s no third party to break a tie in an argument.

Some of the historical details in “This is a Film About The Black Keys” are interesting, including the major role that Beck played in their ascendance when he heard their first CD and got them to open for him. The choice by the guys to reach out to Danger Mouse after hearing “Crazy” is also a neat bit of trivia, given how that song’s cinematic sound feels like a perfect fit with what The Black Keys do. At its best, Dupre’s film does convey the stress of a job in which your livelihood is truly based on production—if you’re not writing, recording, or performing, you’re just going to disappear. And it deftly captures the difficulty of two hard-headed people trapped in that kind of stressful dynamic forever, knowing that they need some sort of compromise to succeed.

Again, it feels like there’s a bit of broader context that might have helped. Most people think that rock is pretty dead right now, so how have The Black Keys defied that? And they’re old enough that you would think we would start to see their influence on the genre, although I’d be hard-pressed to think of too many bands now that sound like The Black Keys. Maybe they’re just so talented that they’re the anomaly in the music scene? While I generally like films that allow their subjects to tell their stories, this one could have benefitted from a bit more outsider perspective on what makes The Black Keys so special.