“I was doing a soap opera in New York. One day, somebody called me and asked if I could come out to Gary, Indiana,” recalls actor J. A. Preston. “Gary, Indiana? Are you crazy?”

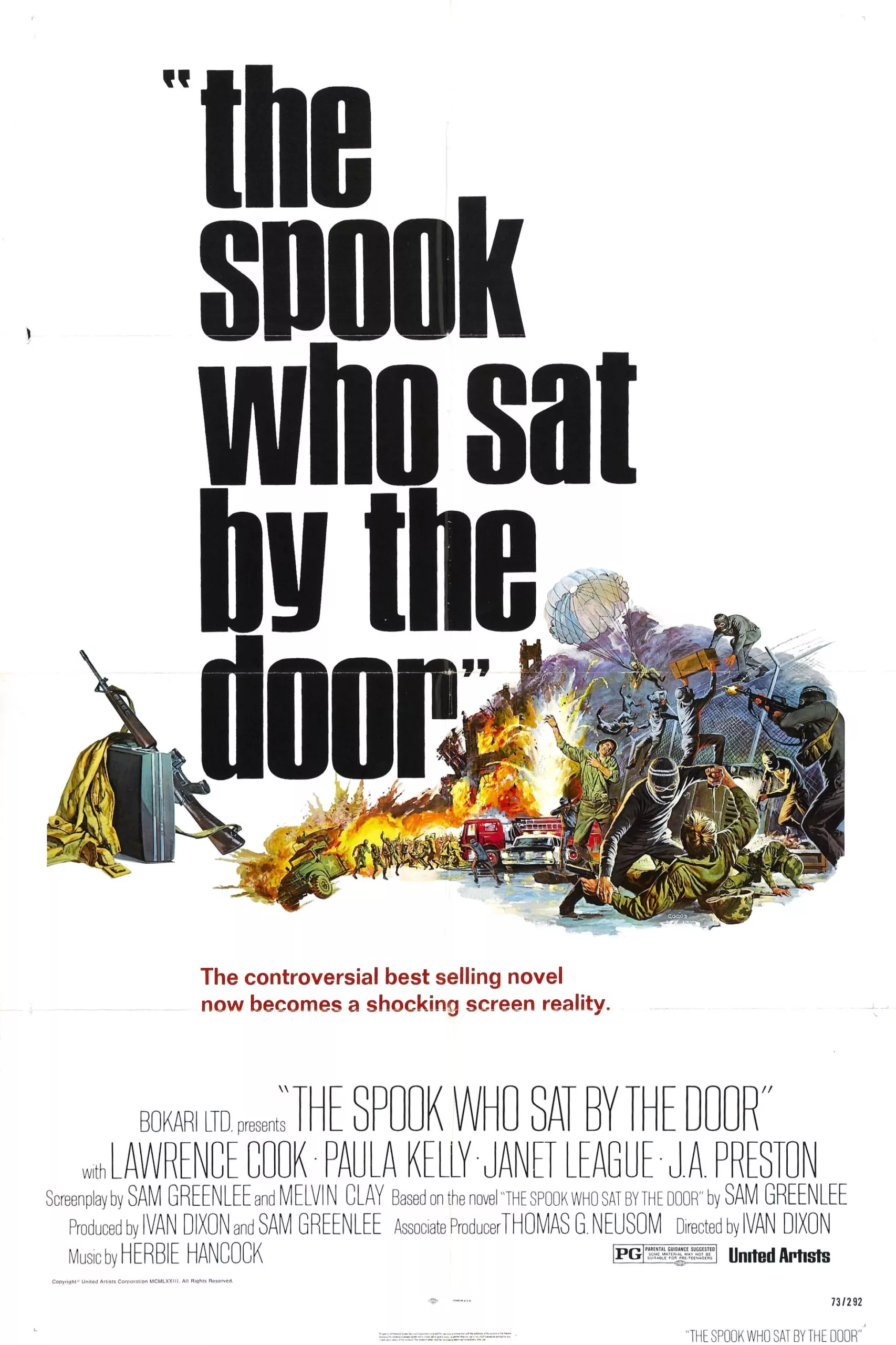

The film that would bring Preston to Indiana was director Ivan Dixon’s audacious adaptation of Sam Greenlee’s radical novel “The Spook Who Sat By the Door.” Made on a modest budget, the film, about a Black ex-CIA agent returning to Chicago to show Black communities the tools for armed revolution, vanished from theaters as soon as it appeared. The film survived only because Dixon kept a 35mm copy, whose materials were later used for a DVD release sponsored by comedian/actor Tim Reid.

Thanks to the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, a little over fifty years following its initial, abbreviated run, Dixon’s fiery masterpiece has been restored, premiering at BAM back in August of this year. The 4K restoration arrived in Chicago as one of the headliners at the 60th Chicago International Festival, where it stands as among the most urgent, imperative works in the history of cinema.

With its return also comes a bounty of memories shared by the film’s few living actors. “Whatever it took to get it done, jiving people, lying and conning, they did it because they were going to get it done one way or another,” recalls the 97-year-old Preston during a conversation at Chicago’s Felix Hotel.

Released in 1973, on the heels of assassinations, college protests, urban rebellions, and the Black Power moment, it’s unsurprising that Dixon and his committed troupe managed to make a Blaxploitation movie unlike any other.

Published in 1969, the novel was partly inspired by Greenlee’s own life. A Chicago native, Greenlee was an agent for the Dwight Eisenhower-founded United States Information Agency (USIA). He served eight years with the USIA in countries ranging from Iran to Indonesia. His eventual novel became a major hit overseas and was the primary text for an American Black populace looking for a handbook for rebellion, which is essentially what Greenlee made. “The Spook Who Sat By the Door” discusses how to make homemade bombs and how to train yourself as a sniper.

Still, by the time the film went into production, Jules Dassin’s “Uptight” (the closest cousin in tone to Dixon’s film), Ossie Davis’ “Cotton Comes to Harlem,” Melvin Van Peebles’ “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” Gordon Parks’ “Shaft,” Gordon Parks Jr.’s “Super Fly,” and many other films had not only defined the Blaxploitation genre. They made the genre — which mostly relied on Black men and women looking to overthrow the system — into enough of a money maker you could see why a studio like United Artists (though to be clear, they became a late financial partner on the film) would be intrigued.

Preston, for instance, remembers living in the basement of a New York City brownstone on 82nd Street when Ron O’Neal, who occupied the first floor, told Preston about a part he landed. “This guy from Cleveland named Phillip Fenty wants me for this role, and it’s a piece of garbage,” Preston recalls O’Neal saying. “Well, he did that piece of garbage for a percentage of the gross, and in six months, that piece of garbage had made $22 million.” The “piece of garbage” was of course “Super Fly.”

Still, few thought “The Spook Who Sat By the Door” would be a similar box office smash. But that didn’t deter many from wanting to be in the film. “People were so happy to be making that movie because everybody was a fan of the book when it came out. It was almost mandatory reading during the sixties,” remembers actor Pemon Rami, who played Shorty, a junkie in the film.

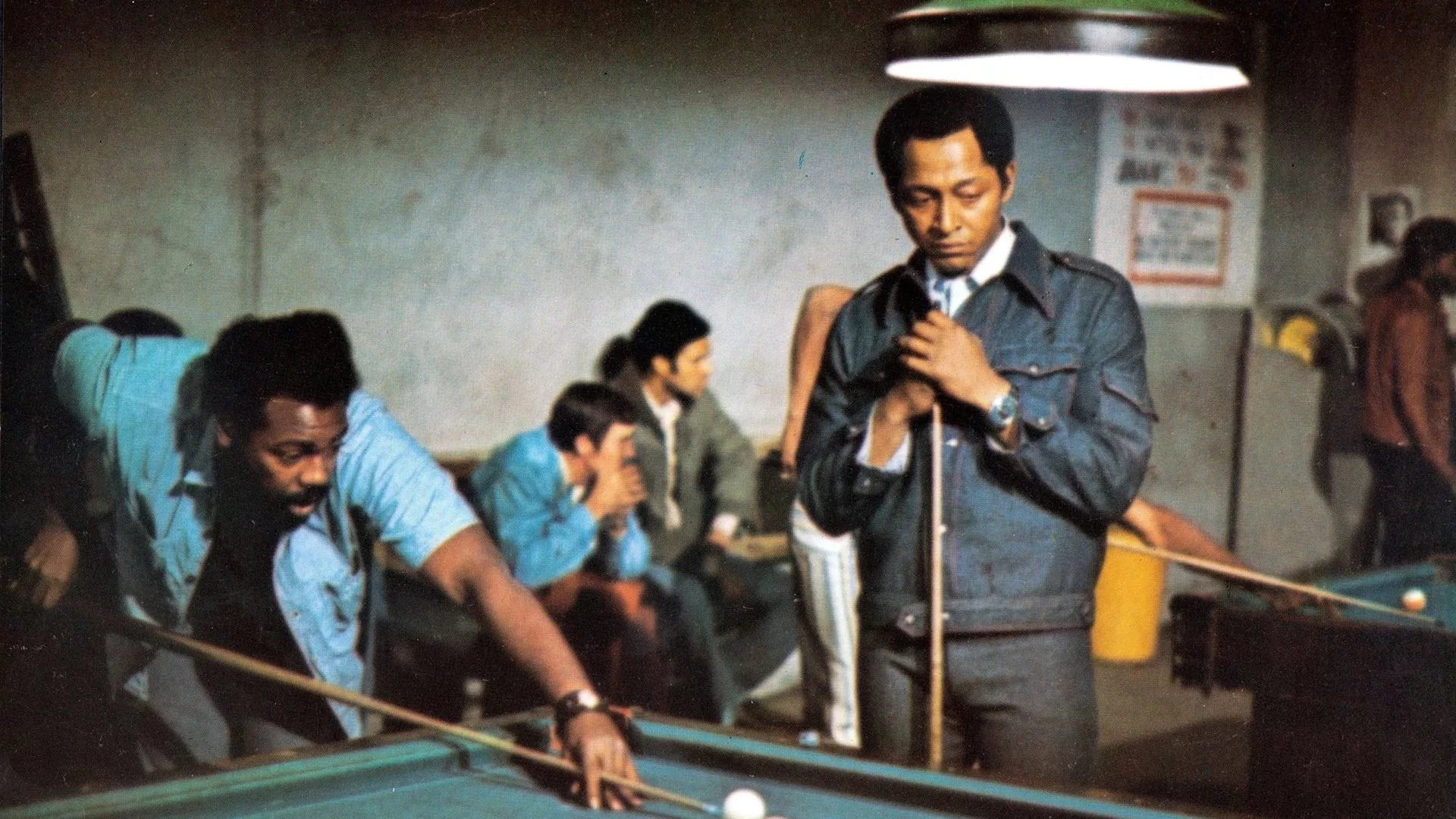

“The Spook Who Sat By the Door” is a fascinating, flinty political tale. The spook, whose double meaning refers to the slur and slang for a spy, is the intelligent and suave Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook), enlisted in the CIA, ironically, to combat accusations of discrimination within the agency. While many expect Freeman to quit under the weight of the exam, he actually excels, learning the secrets of how the CIA destabilizes governments. After leaving the agency, Freeman takes those tactics to Chicago, where he organizes gangs and Vietnam vets in the hopes of beginning a ten-city bid by Black folks to take the country. He gains assistance from lieutenants like Pretty Willie (David Lemieux), a white-passing member of a gang called the Cobras, and he finds plenty of opposition from his longtime friend Dawson (J. A. Preston), a by-the-book cop.

David Lemieux was one of the earliest people to be cast. One of the youngest members of the Black Panther party, he was 16 years old when he joined the party. He first met Greenlee at a Chicago restaurant, where he told the writer how much he identified with the Pretty Willie character. Months later, Greenlee asked for Lemieux to audition for the film, bringing Lemieux, a first-time actor, to his apartment, where Dixon was staying.

“They gave me the script and asked me to read, and I started reading, and they started laughing. I’m 19 years old at the time and somewhat full of myself. I asked: Am I Funny,” recalls Lemieux, “Greenlee said: You had the part as soon as you walked in and opened your mouth. I just wanna make sure you could read.”

Rami joined the cast in 1970 when he was 21 years old. At that point, he was already the director of the Kuumba Theater company in Chicago, and like many others, he was told the part of Shorty was his without needing to audition. Because of his theater background, Greenlee also enlisted him to help with local casting.

Preston, a trained theater actor, auditioned in New York City. “I ran into an actor friend, and he asked if I was up for ‘Spook.’ I didn’t even know they were making it,” says Preston. “He said Ivan Dixon was the director, and of course, I knew Ivan. He was a sophomore at North Carolina College when I was a freshman.”

Though Preston immediately won the part of Dawson, it would be months before he would receive the call to come to Gary, Indiana.

While “The Spook Who Sat By the Door” is set in Chicago, not much of it was shot in the city due to the specter of ‘shoot to kill’ Mayor Richard J. Daley. The film, nevertheless, stuck it to the mayor. In one scene, Freeman and company blow up the mayor’s fictional office. A voice on the radio declares, “The mayor’s office now has air conditioning!” Even so, only a few scenes, primarily those on the city’s elevated train, are in the film. And those sequences required guerilla filmmaking to cast some ground up movie magic.

“We only needed a quarter for those scenes,” says Rami. “We got up to the train and paid our quarter and walked on with the camera. Rode one stop and shot it. Got off and rode the other way for the next shot.”

For the majority of the film, the crew made Gary, Indiana, their home base. Richard G. Hatcher, the city’s first Black mayor, gave Dixon carte blanche. He offered the director a couple of city blocks and other resources to shoot many of the film’s most impressive set pieces.

Additional cost-saving arrived in the form of costumes. Many of the cast, like Lemieux and Preston, wore their own clothes to set. Rami got his clothes from a local Chicago garments shop, while many other articles were donated (Rami’s future wife procured some of the outfits). Almost none of these costumes, like Preston’s maxi suede jacket or Rami’s big-collared jumpsuit, survive today. “I was living with a girl in Boston when I left my stuff there,” remembers Preston. “So maybe her son is wearing my maxi suede now.”

The entire film was a communal effort that required the kind of communal generosity and joint dedication as depicted in the film to succeed.

“People were really interested in being involved,” recalls Rami. “They would bring food and they would participate as if they were almost part owners of the film because that’s how important the movie was. People wanted to see the movie succeed.”

However, despite local support, Dixon and Greenlee perpetually worked to raise funds, which often necessitated pausing production while searching for more investors. During these stoppages, Preston would head back to New York City to work on other projects until he was needed again. At other points, some actors like Lemieux were put up at a hotel in Los Angeles, where the film’s production later moved. While staying in Los Angeles, one incident involving the police acutely represented the totalitarian tactics Lemieux and the film were fighting.

The situation occurred when Lemieux and a couple of people from the film, one of whom had a wooden prosthetic leg, used a local canyon in California as a gun range. They had a couple of firearms from the movie and a shotgun, along with the requisite paperwork to carry them. As they were driving back into the city, however, they were stopped by police at their hotel.

“They had us get out of the car and get on our knees with our hands behind our heads, the usual stuff you see on TV. But one brother was having difficulty getting out of the car,” recalls Lemieux. “I was telling the police: Look, he has a wooden leg. One of the white cops says: That means if he falls in the water he’ll float upside down. Sam [Greenlee] comes running to help with some other members of the crew. Now, the police are pointing the guns at him. He tells them he’s a filmmaker and we’re his crew. Eventually they took us to the station and they ended up letting us go.”

With the aid of private Black investors, Greenlee and Dixon were able to raise $750k. They went to United Artists to get the rest.

The financial difficulties are a reminder that none of the film’s success would have been possible without the steady hand of Dixon. Before “The Spook Who Sat By the Door,” Dixon gained fame as a star on “Hogan’s Heroes.” In the years prior, his other major credits included “Porgy and Bess,” “A Raisin in the Sun,“ “Nothing But a Man,” and “A Patch of Blue.” Similar to other Black actors of the era, many of whom cut their teeth on Blaxploitation films, Dixon moved toward directing, beginning with the Robert Hooks-starring crime thriller “Trouble Man,” which saw Hooks playing a Los Angeles fixer framed for murder. When Dixon arrived on “The Spook Who Sat By the Door,” he came with a reputation as an unfailing professional.

“I don’t wanna sound corny, but for me, at 19 years old, he was a father figure. He was very kind and just a very good brother. He was also low-key. I don’t remember him ever raising his voice or having to yell at anybody,” recalls Lemieux.

“I watched him work on a number of occasions, and he was very calming. He was a really nice guy. It came through in his work,” remembers Rami. “Because it wasn’t just a matter of directing. During that period, you also had to teach actors. Because if you think about during the seventies, there weren’t many professional actors in Chicago. So he had to coach them.”

While “The Spook Who Sat By the Door” leans on its dialogue — Freeman is dedicating much of his time to teaching the tricks of the trade for destabilization — it also features more than a few impressive set pieces, such as a bank robbery where the lighter-skinned Black folks (those who can pass as white) rob a bank. After they’ve committed the brazen heists, they pile into the back of a van, where they pick out their afros and change back into their normal attire. Later on, it’s reported that Caucasian robbers stuck up the bank; thereby demonstrating how, in the words of Freeman, which mirror Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” “A Black man with a mop, tray, or broom in his hand can go damn near anywhere in this country. And a smiling Black man is invisible.”

However, the film’s most incredible set piece is the multi-block revolt scene. Here, Mayor Hatcher of Gary was instrumental: He allowed Dixon to burn down an entire block, provided a helicopter for aerial shots, and allowed the police force to be used as extras. The latter is imperative because the Gary police department was mostly Black, creating a conflicting and complex vision of the limits of integration.

The revolt is spurred by the murder of Shorty at the hands of ultra-violent cops. In the middle of the scrum, the Black officers, like newsreel footage from the South, sic dogs on the Black protestors. Police cars are turned over, buildings are bombed, and Freeman and Dawson confront each other in the middle of the melee. The actual kinetic filming was akin to the raucous scene it was capturing. The set was total mayhem.

“The people we used in the streets for the riot didn’t know what the hell they were doing,” says Preston. “People were throwing bricks and bottles, and it got to be kind of real.”

There even was an instance of locals unwittingly becoming involved in the film. “A lot of those people that ended up joining the action weren’t actors. They weren’t working for us at all. They just came to beat up the police,” recalls Rami. “There’s a scene where there’s a woman fighting with her purse. She wasn’t with us. She just happened to be walking down the street and got involved with it, and they pushed her in, and she fought with the police.”

Despite budgetary limitations and the era’s prejudiced climate, Dixon, Greenlee, and the crew overcame every hurdle. The film premiered in Chicago at the Woods Theater before moving to the Maryland Theater in the city’s south-side neighborhood of Woodland. The film also found its way to the DeMille Theater in Times Square. But it wouldn’t last long in theaters. It quickly disappeared into obscurity.

“Perhaps what led to the mysterious disappearance of the film in many locations less than a week after that premiere was the notion that the government itself created the blueprint Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook) used to direct his rebellion,” writes Odie Henderson in his imperative survey of Blaxploitation, “Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema.”

Indeed, “The Spook Who Sat By the Door” posed a threat to the status quo. At a moment when COINTELPRO was targeting Black political leaders, Greenlee’s book and Dixon’s film showed Black folks how to use those same tactics against the man. Many who participated in the film still actively believe the F.B.I. played a significant hand in its historical and artistic erasure.

It’s probably why Dixon was never given the backing to direct another feature film. He would instead move to television, helming episodes of “The Waltons,” “The Rockford Files,” and “Magnum P.I.” Greenlee later wrote “Baghdad Blues,” which was partly inspired by his witnessing of the 1958 Iraqi revolution, before later becoming poet laureate of Chicago. Preston split his time between theater, television, and film — he is best remembered as Judge Colonel Julius Alexander Randolph in “A Few Good Men.” In 1982, Lemieux joined the Chicago Police Department, where he had a 26-year career. Rami remained in the film industry, serving as a casting assistant for “Blues Brothers” and producing the Robert Tonwsend-Angela Bassett two-hander “Of Boys and Men.”

Some of the talent behind the camera also went on to stellar careers. The score’s composer was Jazz legend Herbie Hancock. Set director Cheryal Kearney later worked on “Coming to America” and “Poltergeist.” Editor Michael Kahn, who initially cut his teeth on “Hogan’s Heroes,” became among Steven Spielberg’s closest collaborators, winning three Academy Awards. Make-up artist Bernadine M. Anderson contributed to “The China Syndrome” and “Another 48 Hrs.”

Due to Tim Reid’s efforts to put the film on DVD in 2004, there would be a documentary about the film’s making called “Infiltrating Hollywood: The Rise and Fall of the Spook Who Sat by the Door.” The film would also eventually be added to the National Film Registry in 2012. Dixon, who passed away in 2008, was fortunate enough to see the film gain a new audience. But even that resurgence could never rectify cinema’s loss. What might Dixon have done as a director if “The Spook Who Sat By the Door” hadn’t been torpedoed by quite possibly the government and the era’s leading (white) film critics?

As Henderson notes: “The Big Apple’s best had a field day of faux outrage. Jerry Oster in the New York Daily News was either feigning ignorance of slang or was really that dense when he wrote, ‘The Spook Who Sat by the Door’ is not a ghost story.’ He also misrepresented the final scene between Dawson and Freeman and said that the film ‘begins as a comedy, middles as an adventure and ends as a tragedy.’”

“The Spook Who Sat By the Door” has recently been re-evaluated by critics. Back in 2014, Richard Brody wrote in The New Yorker, “The movie is also a distinctive and accomplished work of art, no mere artifact of the times but an enduring experience.”

The new 4K restoration of the film is the latest effort to rectify the loss caused by white critical negligence and underhanded dealing. During its screening at the Chicago International Film Festival, Lemieux, Rami, and Preston gathered again to talk about the film — offering the audience at the city’s south side Logan Center memories that filled the space with the radical spirit of the comrades who pushed the film into fruition.

“People are still talking to me about it; they’re still rediscovering it, and it’s being taught in schools. How much can you ask for,” wonders Rami. “The project that you did in 1972 and was released in 1973, in 2024, still has people thinking about it. This is a story that’s going to last for generations.”