“We Need to Talk About Cosby,” W. Kamau Bell’s brilliant four-part documentary on Showtime, is crucial viewing. Why? Because some people still don’t believe in his guilt, his 2018 conviction for aggravated indecent assault was overturned, and he’s walking around entertaining the possibility of a book and documentary (an unexpected coda which Bell hadn’t anticipated but includes in the series). And because Cosby was hiding in plain sight, a wolf (apologies to wolves) in sheep’s clothing despite the hints he dropped. And there were plenty. My jaw was on the floor as I mentally reframed scenes Bell highlighted from “The Cosby Show” featuring Doctor and Mrs. Huxtable’s frisky banter about what was really in his barbecue sauce! I reeled when realizing Doctor Huxtable was not just any kind of doctor, he was an OB/GYN who examined women in his home office! My god. He was toying with us, almost daring us to find him out, so secure was he in the notion that he was unassailable even as he assailed scores of women who crossed his path.

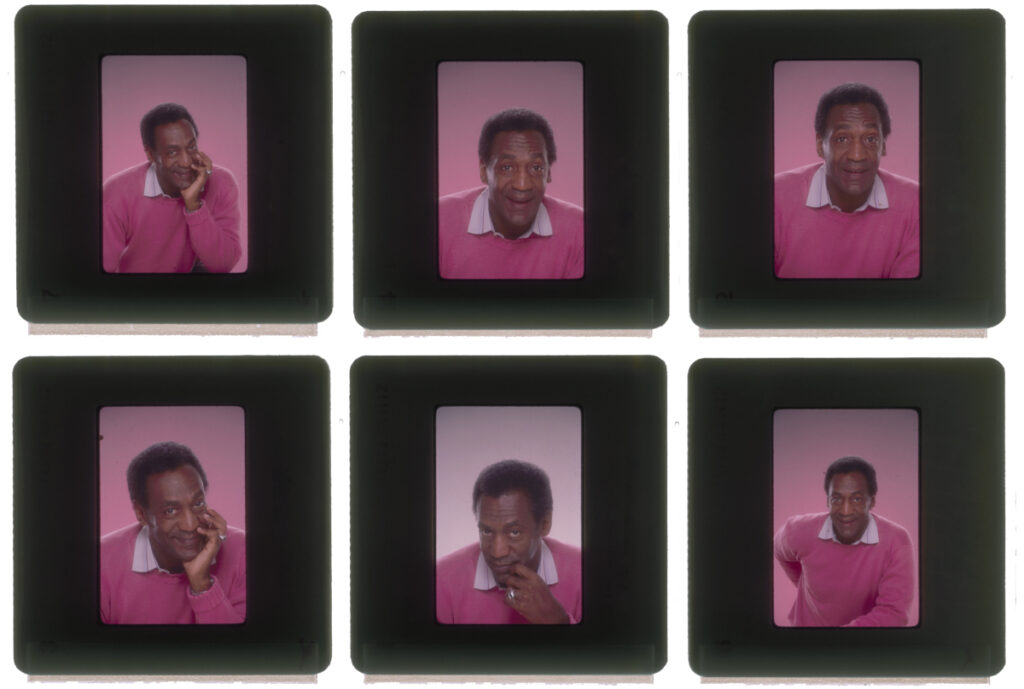

I need to talk more about Cosby because I’m still trying to get a grip on how such wildly different personas could co-exist in the same person. Bell creates a potent context for Cosby’s deviance. Better than anyone has done before, the series fleshes out the depth and breadth of Cosby’s impact on mainstream culture. Cosby became a colossus astride the racial divide, across many decades and multiple mediums—stage, screen, the written word—and as an entertainer, author, educator, academic, political activist, moral authority, father figure. Perhaps most significantly, he reconfigured representation in primetime for what an all-American family looked like: Black, upwardly mobile, smart, wholesome, sophisticated, professional. His public and private personas were merged in the mind of the public. Not our only mistake.

What struck me most, and as Brian Tallerico notes in his review, is that Bell’s series makes a stunning reality graphically clear: Cosby was traveling two concurrent trajectories. In every decade on his journey to becoming a beloved pop cultural icon and the apotheosis of racial equity, he was simultaneously drugging and raping women. How could this all be true of one and the same guy?

One answer lay in his unique gift for reading an audience. He could see and understand us, reach us, put us at ease, and tell us a story in such a funny, vivid, relatable way that we’d follow him anywhere just to see where he might take us. It’s a manipulation, a seduction of sorts, to achieve a desired effect. It’s what any skilled actor, comedian, writer, performer does. It’s the gift that keeps on giving, even when you know better, even when it’s in service of a deviant personality.

Cosby also put those skills in service of an aberrant fetish which coupled complete domination (an unconscious woman) and sexual stimulation to make him an ungodly predator of biblical proportions. Was that fetish an extension of the kick he got from holding an audience in the palm of his hand? A perversion of his need for control? A permutation of the sex and drug culture of the swingin’ ’60s? We’ll most likely never know. Bill Cosby himself is not talking about Cosby.

Even more disturbing to me was watching brave women unsparingly describe, direct to camera, what Cosby had done to them, and then, almost without exception, blame themselves first for what happened! It struck me like a cold wind. It was a troubling throughline in all of the hideous stories they told.

By now, we understand the ways in which women are acculturated to feel guilty about sex, to defer to power, to avoid conflict. No surprise that most of the women who came forward, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, felt like somehow it was their fault and told themselves they had given Cosby the wrong signals, shouldn’t have put themselves in that situation, or shouldn’t have had that drink.

Only Beverly Johnson the first African-American model to grace the cover of Vogue Magazine castigated Cosby on the spot. As soon as she felt the first signs of drowsiness after the cappuccino he’d given her, she knew the “motherf—-r” (her word) had drugged her and called him out. As a worldly, successful supermodel who had crossed the racial divide herself, she was no doubt less intimidated in the company of a powerful Black icon. Even so, Cosby almost succeeded, but, in the face of her protestations, he piled her into a cab before he could complete the assault.

My very wise daughter reminds me that self-blame is a fundamental psychological defense mechanism. It feels safer to imagine there was something you might have done differently which could have prevented the assault. Blaming yourself prevents you from having to accept the terrifying reality that you were, in fact, completely helpless and vulnerable through no fault of your own—and that it could happen again. The fact that it often takes years for women to come forward, if ever, bolsters the argument.

I can’t help but recall an assignment I had in 1997 as a TV Arts and Entertainment reporter for CBS Boston. Bill Cosby was appearing in Lowell, Massachusetts and I was to interview him and cover the show. He was also promoting his new “Little Bill” series of children’s books, one of them on how to handle a bully.

That afternoon, I interviewed him, and had also arranged for him to read aloud to a group of elementary school kids. What happened next seemed out of character. He appeared to make fun of the kids. One little girl was visibly uncomfortable after she raised her hand and answered a question, only to have him belittle her answer. The child grew silent. I was uncomfortable, and so was my producer, who can spot a phony a mile away.

“But he’s an educator,” we thought. “He’s good with kids, right? He thinks he’s being funny, but he has miscalculated.” We rationalized that it must be a rare off moment. We were also invested in believing in Cosby—he was our story that night, and we didn’t quite trust our negative gut responses to his interaction with the kids. We might be wrong.

Then, as he got up to leave, I remember him walking by, leaning in, and saying “FOLLOW ME” as he kept walking. HUH? I looked at my producer. Should she and the crew follow too? Was this about shooting that night’s show? Who knew? Maybe I was going to get the inside scoop on Jell-O Pudding pops.

In any case, if Cosby called, I was going, and it seemed clear the invitation was for me only. I followed him down the hall to his dressing room. He walked me in, took off his jacket, motioned to the couch, offered me something to drink, and asked me to sit down. I declined the drink but sat down. He sat down next to me. He didn’t say a word. He stared straight ahead, expressionless. It was suddenly as if Cosby had left his body and another entity had taken his place. Creepy silence.

What the heck was I doing there? What should I say? I was wracking my brain and remembered that about a year before, Cosby’s adult son Ennis had been murdered in a roadside mugging—should I offer my condolences? No. Too personal. Oddly, I felt like I couldn’t just ask why he wanted to see me. Maybe I was supposed to know? Maybe I somehow didn’t want to know? I managed to say something about how much we were looking forward to his show that night. He said nothing.

Then he got up, walked to the door, opened it, thanked me, and ushered me out. I walked down the hall in a daze, feeling like I had just failed some unspoken test. My producer was waiting for me. I didn’t know how to process what had happened.

I didn’t think much more about it until years later when one night, in the middle of his routine, stand-up comedian Hannibal Buress galvanized the rumors that had been floating around Cosby for years, and finally blew the roof off the house that was Cosby. In unnerving retrospect, the pieces of my encounter with him fell into place—had I been a potential victim?

I realized I’d had a glimpse of the hidden man, but W. Kamau Bell, along with the brave women who made themselves vulnerable to talk about Cosby again, have brought the man into sharp focus. It’s hard to look squarely at the dangers around us, but this series, like all excellent documentaries, helps us do exactly that.

By putting the past in revelatory perspective, Bell’s series invites us to think about how and why we hide uncomfortable truths from ourselves, and how our individual and collective vulnerability to fame, power, and the heroic myths we construct fills our needs and disarms us even after we’ve been betrayed. How much we “needed Cosby” is one of the reasons “We Need To Talk About Cosby.”

Ultimately, the series reveals the courage it takes not only to admit our vulnerabilities, but also suggests that by embracing them we are on safer ground. There will always be dangers afoot, but the light of chilling hindsight, through the eyes of those who dare to name them, can illuminate a way forward and let us know we are not alone in the dark.