In a prickly interview for the BBC in 1976, Sam Peckinpah unpacked his relationship with bloodshed. His films, which so often showed brutal massacres, were meant to reflect what he saw in the world. “Let’s look at the facts,” he said. “Most violent crimes are committed by the family or close friends, most violent deaths are involved with people involved with each other.” At the heart of Sam Peckinpah’s violence is the anxiety of being strapped to a lit fuse: the person you love most is the most likely person to strike you down.

Peckinpah was a deeply introspective man who, for better and for worse, fought with his demons on screen. In interviews, he invokes catharsis as an explanation for the violence in his films. It was more than just the reality he saw around him, but a means of channeling his rage into something creative. He wanted to show violence as it was: bloody, messy and ugly. Peckinpah hoped that in watching violence he would help weed it out of the real world. Looking at his films in light of The Film Society of Lincoln Center’s presentation of “Bring Me the Head of Sam Peckinpah” this weekend allows deeper examination of how the director worked with violence and masculinity.

“I love you,” Benny (Warren Oates) whispers to his fiancee, Elita (Isela Vega), shortly after she is raped in “Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia.” Sitting at the bottom of a shower, he holds her naked body, soaking his sweat-stained suit as he tries to comfort her. A day earlier Benny had asked her to marry him, even though it’s not something he particularly wants—but he is willing to compromise to make her happy. Benny really loves Elita but allows his insecurity to blind his affection.

This moment of gentleness is counterbalanced by his obsessive and ugly quest to recover Alfredo Garcia’s head. The sexual violence experienced by his wife-to-be only serves to strengthen his resolve, in spite of the fact she begs him to drop it all and run away with her. Emotionally wounded and faced with a crisis of masculinity, Benny is the ultimate Peckinpah surrogate and he allows violence to infect his life. He cannot see that Elita is not interested in his performance of masculinity and has no desire to become intertwined in the brutal world of crime. Benny’s violence is born out of powerlessness. Violence grows in him over his feelings of inadequacy, but, in particular, his relationship with Elita. As much as he loves her, he senses that he is not man enough for her.

He ignores the fact that Elita gives herself up to be raped in order to save both their lives. This final act of selflessness could have easily purged them of their former life, but Benny continues to lead them both towards their death. Elita responds gently to her rapist; she doesn’t fight back but softly and calmly begs to be let go. Her strength is palpable and challenging to audiences because Peckinpah doesn’t depict her as having shame about her body. Rape, like most violence in Peckinpah’s work, is rarely the way we imagine it. The scene is loaded with layers of tragedy: the sense that Elita had been raped before, that Benny cannot save her and that her rapist would choose to hurt her for no particular reason.

Peckinpah’s preference for slow motion and intricate cutting amplifies scenes of cruelty, having them echo through time and spill into subsequent scenes. His best films are built around harsh and disorienting cuts; the impact of violence built through contrast, especially through the manipulation of temporality with slow motion. In the time it takes for a body to fall to the ground, bullets fly, people die, and an entire scene unfolds.

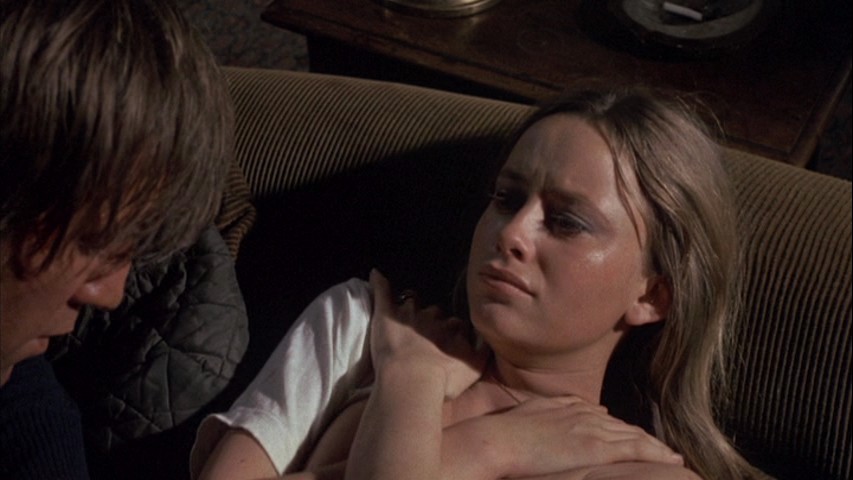

In “Straw Dogs,” montage is used to suggest the chaotic aftermath of rape as Amy (Susan George) tries to hold onto life after being attacked by her former lover and his friend. Her relationship with her husband David (Dustin Hoffman) is already so strained that she can’t communicate her experience, and only further resents him for his obliviousness to her pain. She chastises him for being a coward, unable to stand up to the men who raped her. Days later, haunting flashes of violence overwhelm her during a talent show at the church. Chaotic and artfully rhythmless, shots are intercut, the action having no discernible pattern. It is brutal and jarring, absolutely overwhelming.

The pain in “Straw Dogs” is crippling. The violence pierces through a crumbling relationship to reveal what most people in a committed relationship fear: being hit with the realization you’ve married a stranger. “Straw Dogs” is not a fascist fantasy for meek males, but a horror story of an ordinary, cowardly man, gone mad. Violence traps us, forces our failures onto the ones closest to us. David is put between a rock and a hard place, he must defend his home; violence pushes him into a corner. What choice does he have?

“You’re an animal,” David teases Amy again and again. Her hunger for sex is exciting but frustrating for him. He wants to dominate every discussion and every interaction, so he reduces her to an animal and a child. Peckinpah begins a scene after the worst of an argument has ended. Amy is on the brink of tears and David accuses her of childishness. David knows how to hurt her, and it’s clear that Amy’s relationship with violence goes back further than her marriage. David might not hit her, but he denigrates and humiliates her. “Why don’t you grow up?” He screams at her. She had just been raped but he was annoyed that her “friends” had left him on the moor.

In “The Getaway,” the central marriage between Doc (Steve McQueen) and Carol (Ali McGraw) is similarly marked by violence. While among Peckinpah’s least personal films, the movie is punctuated by frustrated moments of abuse. After Carol ruins their plan for escape after a heist, Doc pulls up to the side of the road. He raises his hand above his head to hit her, she flinches but he doesn’t deliver the blow. Her hair is tangled, she is in terror. He changes his mind, grabs her by the hair and beats her. He “doesn’t mean it,” of course, but Peckinpah doesn’t let him get away so easily. The scene is unflinchingly harsh and contrasts so powerfully with Carol’s selfless loyalty up until this point. McQueen may have been the coolest person in the world in 1972, but Peckinpah renders him a monster.

The intimacy of violence has always been the most striking part of Peckinpah’s work. As each film painfully deconstructs how bloodshed and brutality wear away at our humanity, the worst of it is usually leveled against the ones we love most. Violence and abuse take on many forms in Peckinpah’s work and more often than not is matched with loaded contradictions. Violence is sometimes a reaction, but often times is a choice: the men in Peckinpah’s world choose to hate when they could have love. They feel inadequate, weak, unheroic, and act out of desperate self-destruction against those who love them most.