In 2006 I had the great fortune to attend the Cannes Film Festival, and after it was over I had the diverting good fortune to be seated on my return flight next to a talented and relatively well-known young actor. We were both in economy—the movie she was repping at the festival was a low-budget one—but in the section right behind first class, so we had a lot of legroom and the ride back to New York was hardly uncomfortable. She herself created a slight sprawl, as she had a lot of books with her that she kept going through kind of randomly. They were her own journal/notebook, a volume of poems by Leonard Cohen, and a translation of Notes on the Cinematograph, in this edition titled Notes on Cinematography, a slim volume of epigrammatic instructions and observations by the French director Robert Bresson, whose 13 feature films made over a 40-year period constitute one of the most distinctive bodies of work in any art form.

Bresson’s book was about his methodology, which was unusual. He believed that the theater and the cinema were such different art forms as to be completely alien from each other, which many today might regard as an eccentric view to say the least. (The quality of critical attention applied to playwrights turned film directors is a revealing indicator here). Hence, he did not believe in acting in film as such and referred to his performers as “models.” He stressed simplicity of method, but not for the end of articulating a simplistic perspective. To put it concisely, his way of seeing and of communicating what he saw was unique, and not necessarily reproducible, although had he not wanted to spread the word on his way of working, he might not have published his musings on it.

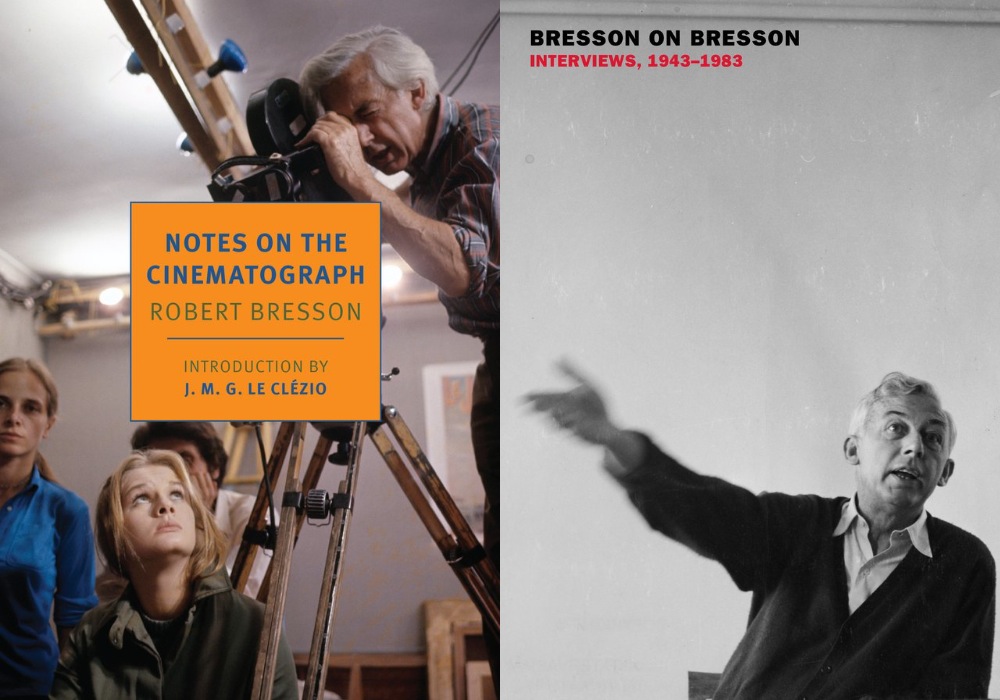

At one point in the flight I acknowledged the Bresson volume to my traveling companion and said, “That’s an interesting book.” She enthusiastically responded, “It’s a beautiful book.” She was right. Now reprinted by New York Review Books in a new translation, with, among other things, a more accurately decoded title, Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematograph is a version of Flannery O’Connor’s Prayer Journal for the cinephile. It’s that concentrated, that profound.

It is also, seen from the point of view of a would-be filmmaker in the world as it is today, perhaps, filled with a kind of magical thinking. “To TRANSLATE the invisible wind by the water it sculpts in passing.” “Don’t show all sides of things. A margin of indefiniteness.” These aren’t exactly practical tips. Then again: “To be constantly changing lenses in photographing is like constantly changing one’s glasses.” To Bresson, whose masterpieces “Pickpocket,” “The Devil, Probably,” and “L’Argent,” among others, progressed to their implacable conclusions by way of a locked (and loaded, in a sense) point of view, the fix is the point. Sidney Lumet, whose own book Making Movies has a nuts-and-bolts approach that doesn’t lack for philosophy but certainly doesn’t privilege it, might argue that it is only by “changing one’s glasses” (as he did with the ever-perspective-shifting “Prince of the City”) that one can create the desired effect. Bresson’s book is a good one to argue with.

When I was discussing it with that actor in 2006, I noted that its practical application in a Hollywood context might be impossible, and she shrugged me off. She was correct; as it happens, Bresson is a filmmaker whose influence extended to Hollywood, albeit in piecemeal ways, and via one-time industry outliers such as Schrader and Scorsese, but it’s kind of not important whether or not he’s consciously imitated. It is unfortunate that we have an industry whose workings are hostile to an artist of this caliber, but as the relative paucity of Bresson’s output attests, producers weren’t exactly beating a path to his door in France, either. At the end of my conversation I tried to tweak the actor a little bit by mentioning that the seemingly ascetic “Goldfinger” was a big favorite of Bresson’s, but that didn’t get much of a rise out of her. His pronouncement of that film as “formidable” has, of course, to do with its utter estrangement from theatre—its content aside, it does indeed stay put in an entirely cinematographic world.

That interview does not appear in the other NYRB volume of Bresson, Bresson On Bresson: Interviews 1943-1983, edited by his widow, Mylène Bresson. This invaluable book is first off extremely useful in making the Bresson of Notes on the Cinematograph seem a far less hermetic figure. An early pronouncement, from an interview about his 1943 “Les Anges du péché,” strikes one as useful in any endeavor: “A good craftsman loves the planks he planes.” In 1950 he says his about music in film: “Too often the music in a film exists only to prepare the audience to receive the film, to sense it better, to put viewers in a state that will permit them to better receive it; but I think of this as a mistake. It’s imperative we find other ways.” Put this way, as opposed to the epigrammatic “pronouncement” form of the apercus in Notes for the Cinematograph, the thought becomes part of a provocative potential argument. Is music not a nearly-native component of film language? Does the ostensible overuse of music demand that a true cinematographic artist abandon it entirely? And so on.

The book is not just of interviews but of writing by Bresson commissioned by film magazines. These shed possible new light on the man and artist for the English-speaking cinephile. But they don’t make the experience of the work any less powerful or mysterious. In one late essay in the book Bresson explicitly identifies himself as a “Christian filmmaker,” but ultimately it’s up to the viewer to figure out the way in which that is pertinent. Bresson’s faith and the way it’s expressed in his works can lead to some bizarre critical pronouncements; I once read a very seriously-toned essay in which the author asserted that atheist film critics could not honestly admire the work of either Bresson or Tarkovsky because a true appreciation of the work had to be predicated on an acceptance of their faith. But cinema is about more than ideas or ideology—to paraphrase Scorsese, it is first and foremost a matter of what’s in and what’s out of the frame. Which is why such ideologically repellent films as Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” and Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” continue to elicit critical praise and historical recognition. It’s also why it’s so difficult to figure out whether Bresson’s incredibly grim and final project, “L’Argent,” is a Christian film, the film of a lapsed Christian, or neither. In any event, it is a film of absolute integrity, and an undeniable one. One of the last entries in his Notes on the Cinematograph is this: “MAKE YOURSELF BE BELIEVED. Dante in exile, walking in the streets of Verona—people whispered to each other that he goes to Hell when he chooses and brings back news from there.”

To purchase a copy of Notes on the Cinematograph, click here.

To purchase a copy of Bresson on Bresson: Interviews, 1943-1983, click here.