After a very funny and cheeky opening note titled “Dear Reader,” in “Eve’s Hollywood,” the splendid early ‘70s book by Eve Babitz, newly reissued by NYRB Classics, there are eight pages worth of dedications. The breeziness of the writing both here and in the opening note suggest, at least slightly, the sexist term “ditzy.” The profligacy of her gratitude could also be said to have a name-dropping aspect: Linda Ronstadt, Ahmet Ertegun, and Stephen Stills pop out to the classic-rock-oriented page skimmer, for instance. But two lines, very close to each other, stood out once I was deeper into the book: “To Marcel Proust” and “To ‘LUNCH Poems’.” These strike me as key to understanding the appeal of Babitz’s prose.

Like the divine Marcel, Eve Babitz is here concerned with memory and consciousness. “Eve’s Hollywood” is a wide-ranging inventory of anecdotes that make up something like an autobiography of the early Eve, the Eve who grew up to be a near-ubiquitous figure on the Los Angeles cultural scene. And if you just snorted “WHAT Los Angeles cultural scene?” this is a book you need to read, even more than you need to read “City of Quartz” or “City of Nets,” two other notable tomes on the same theme. While those two books make the case from the perspective of the philosopher and the historian, Babitz gets her cred from a boots-on-the-ground perspective that once found her playing chess nude with Marcel Duchamp. Which is one way of saying that Babitz’s explanation of Cultural L.A. is more fun than Mike Davis’ or Otto Friedrich’s, not to mention Joan Didion’s.

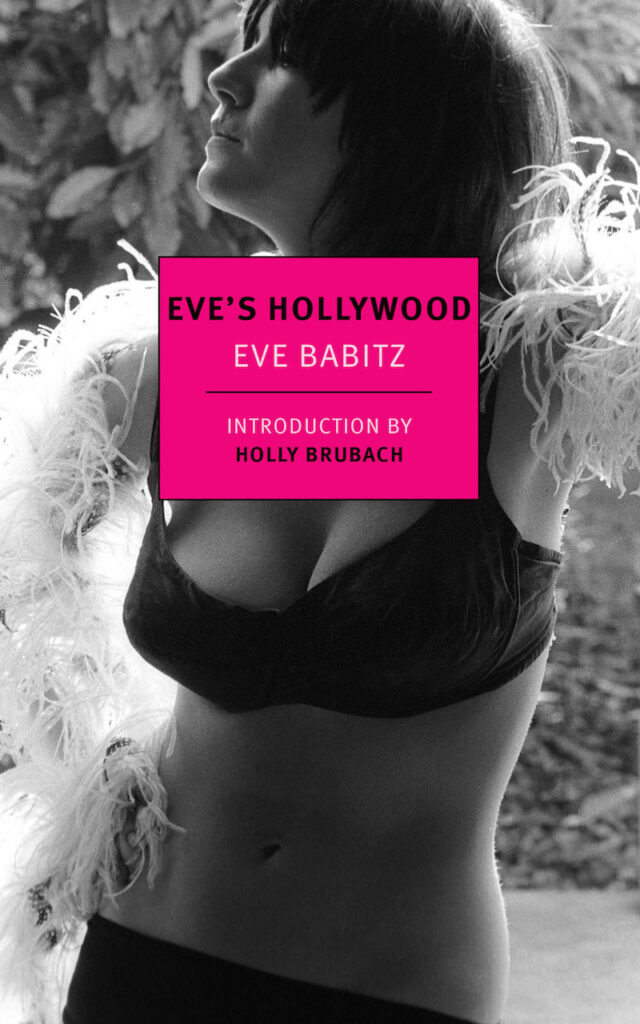

As for “Lunch Poems,” Frank O’Hara’s groundbreaking collection was exuberant in both its language and its unabashed honesty and enthusiasm, and here too Babitz is a champ. The future author of a novel called “Sex and Rage” is pictured on the cover of this reissue in an Annie Liebowitz shot from 1974, of the young Babitz resplendent in black bra and panties and a white boa, vamping it up most unselfconsciously. Babitz’s I-enjoy-being-a-girl girlishness actually constitutes a dialect in this book, one she uses to frequently devastating effect. Whether examining her father’s place in the hierarchy of the musical world he loved (Sol Babitz was a violinist in the 20th Century Fox studio orchestra but also a friend of Stravinsky and Schoenberg and a pioneer of early music research) or parsing the relationships between girl cliques at Hollywood High, Babitz demonstrates an also-Proustian concern with arcane social codes. But she’s never not funny about it, which you can’t necessarily say about the author of “In Search Of Lost Time.” (Unfortunately there’s one reference to the writer late in the book that illuminates the casual homophobia of Babitz’s generation, but that’s life.) “In the scheme of things, I was in the second circle of popularity, which wasn’t as bad as being nothing at all but was certainly not as good as being anything in the center,” she notes in her chapter about The Polar Palace, a very improbable-sounding L.A. skating rink she frequented in the ‘50s.

You may be asking right about now: What does any of this have to do with movies? Well, honestly, not much, at least not overtly. But the book IS called “Eve’s Hollywood,” and with good reason. While Babitz herself was pulled professionally more into the music side of things (she designed album artwork for more than a few of the rockers mentioned in her dedications), the biz, such as it was, looms over almost every aspect of interaction in this book. There’s a whole chapter discursively devoted to Valentino. What Babitz illuminates about the social/cultural life of Los Angeles is how every discipline bled into the other. “Culturally, L.A. has always been a humid jungle alive with seething projects that I guess people from other places just can’t see,” she writes early on. A little later, she says, “[T]here was never any visible Hollywood, thought by 1956 even the invisible Hollywood was being ground under the spurred heels of Brando’s Zapata.” Her love of the place eventually compels her to brand the author of “Day of the Locust” a “creep,” and by the time she delivers that verdict you’re ready to believe her.

A lot of this has to do with the author’s somewhat charmed life, and her undeniable charm—in a section in which she leaves L.A. for a sojourn in New York that makes her love her hometown even more, she manages to arrange a meeting between Frank Zappa and Salvador Dali—but her smarts and friendliness in this book are such that only the curmudgeonliest churl could hold any of it against her. “Eve’s Hollywood” is a cockeyed place, and I’m not even sure it exists anymore, but it’s a real pleasure to visit, and anyone interested in Hollywood the large concept kind of needs to experience it.