Though they are not featured in it, the people of Gaza are recognizable in Raoul Peck’s radical, unsparing, and wholly vital four part documentary “Exterminate All the Brutes.“

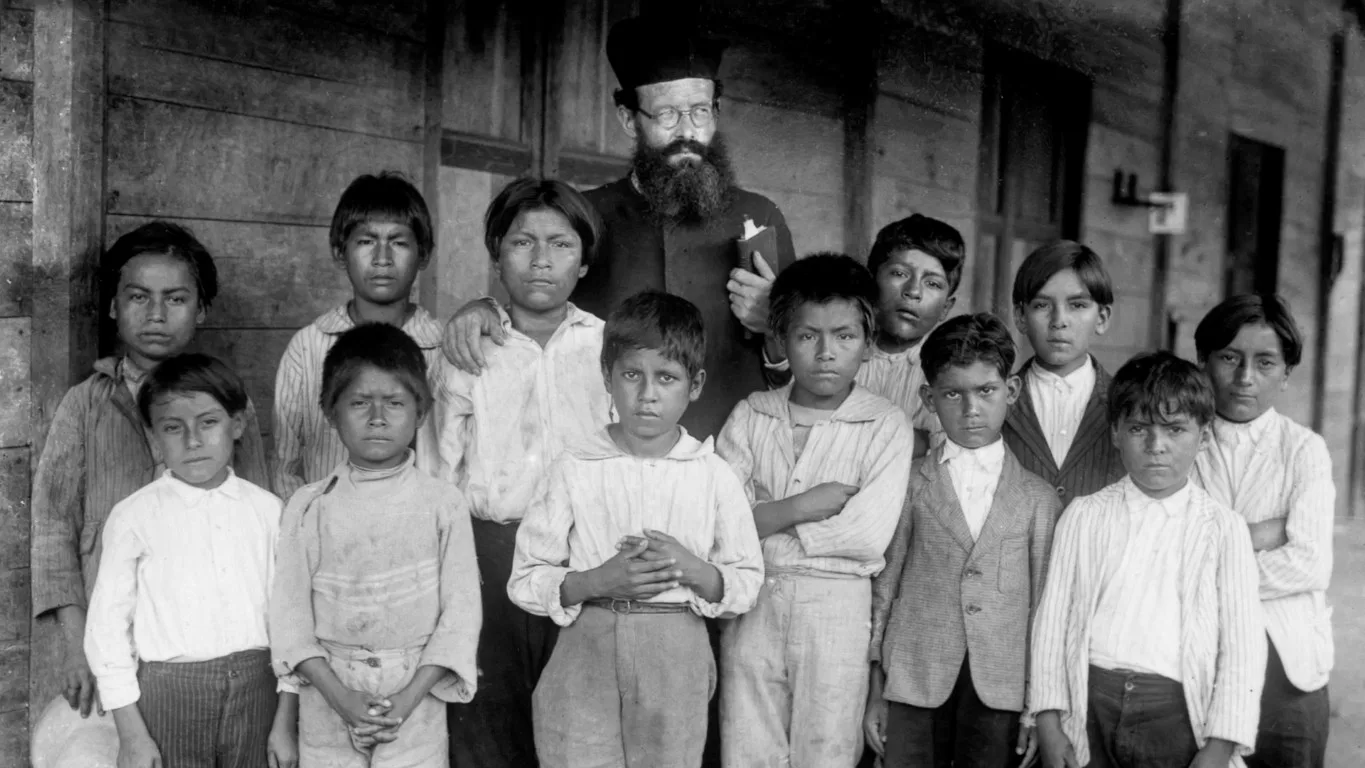

The film, an ambitious cinematic essay on the history of genocide and Western un-civilization, debuted on HBO in April 2021. In it, Peck identifies white Christian supremacy and a fixation with “clean blood” as the thread stitching together campaigns of colonialism and genocide since the Spanish Inquisition of the 15th century.

Over and over, Peck makes legible a cycle of violent domination fueled by false hierarchies and real dehumanization: civilization, colonization, and extermination. Palestinians have been familiar with such a cycle since at least the Nakba, or Catastrophe, of 1948 which saw the violent expulsion of at least 700,000 people from their homeland, followed by occupation and mass dispossession.

“We would prefer for genocide to have begun and ended with Nazism,” Peck says, noting that the mass slaughtering of peoples has regularly taken place both before and following the Holocaust, often with weapons made and sold for profit by the United States. Indeed, as James Q. Whitman writes in Hitler’s American Model, the Fürher’s expansionist Lebensraum campaign was inspired by the American genocide of Indigenous nations that came to be branded as Manifest Destiny.

“Exterminate All the Brutes” debuted at a time in which modern humanity’s very understanding of itself had been upended by covid-19. The previous summer, record numbers of people flooded into streets to protest the breathtaking horror of watching a police officer asphyxiate the life out of a man named George Floyd for nine minutes as he begged for mercy, for air, for his mother. All over the globe, people were naming and shaming white supremacist oppressors, tearing down their monuments and in some cases, hurtling them into the Thames, as was the case with a statue of English slave trader Edward Colston. In Belgium, protestors defaced statues of King Leopold II, the brutal monarch whose grim, bloody reign in the Congo features heavily in Peck’s film. If ever there was a time when the world might shake itself awake and actually appreciate what Peck was attempting to communicate, it was then.

Alas, January 2021 was also when a group of violent insurrectionists set upon the United States Capitol with wooden gallows, calling for the execution of then vice president Mike Pence. Unable or unwilling to believe that Joe Biden had won a free and fair presidential election, Donald Trump’s most rabid supporters conducted an ugly, violent, hours-long siege. Those who were incarcerated for it were rewarded this year with pardons when Trump reassumed office, having won a second and final term.

I thought it worthwhile to revisit “Exterminate All the Brutes” now, as a second Trump administration attempts, with more efficiency and success than the first, to assert an international racist hegemony championed by far-right leaders such as Viktor Orban, Geert Wilders, Marine Le Pen, Jair Bolsonaro, Nigel Farage, Vladimir Putin, and Benjamin Netanyahu. A hegemony in which objection to the systematic murder, rape, mutilation, torture, terror, starvation, and plunder of various peoples is waved away, more or less, as woke nonsense. What could Peck’s unifying history of these violences offer us now, in an era in which genocide can be live-streamed on TikTok?

The answer, I think, is the embrace of humanity, intimacy, of bearing witness, in the face of overwhelming efforts to distance, to dehumanize, to render a daily onslaught of lopsided trauma morally inert. Part I of “Exterminate All The Brutes” includes themes of cultural and media literacy, as Peck illustrates how pop culture can deaden the senses to the point of misinformation. Using his chosen medium of cinema to illustrate what he means, Peck attempts to highlight and unwind the seductiveness of slaughter as embodied by John Wayne, using actor Josh Hartnett, who began his career as a millennial teen heartthrob, as an avatar for white colonizers through multiple locales and periods.

He uses another actor, Fraser James, as an avatar for himself, going so far as to stage scenes in which James encounters a coffle of kidnapped white children and beats one with a lash, inviting us to ask if the reign of terror known as the slave trade could have been sustained if the races of victim and victimizer were reversed?

Peck relies heavily on historical re-enactments to join and punctuate archival footage and photographs. He draws the viewer into the circumstances that surrounded their capture and composition, bringing the abstract of black-and-white still images into the full dynamism of movement and color. The Haitian-born Peck, whose family often traveled and worked internationally, including in the Congo, as they attempted to outrun the dangers of their own dictator, François Duvalier, also incorporates footage of his own family and upbringing, braiding them into the stories of conquered peoples whose faces and stories are so often reduced to abstraction.

“Why do I bring myself into this story?” Peck asks. “Where do I fit in it? As a filmmaker, I am compelled to stay hidden in the background. Restrained. Moderate. Balanced. Judicious. Neutral, even. You learn to avoid becoming the subject of your film. It’s not about you. Unless the story is bigger than you. In that case, you go for broke. Neutrality is not an option. And those who seek history with an upbeat ending, redemption, or reconciliation may search in vain. Such a conclusion cannot be expected.”

“I am an immigrant from a ‘shithole country,’ like [Trump] said,” Peck reminds us in his steady, baritone narration.

Gaza is one of multiple places in the world, including South Sudan and Yemen, experiencing ongoing destruction, starvation, dispossession, and bombardment. It is one of multiple places full of desperate people wondering why the rest of the world has forsaken them. But Gaza is also the site of the most undeniably recognizable genocide of an era in which the simple invocation of the word “genocide” sets off protestation, never mind the fact that Israel has killed at least 55,000 Gazans since 2023, most of them women and children, merely the latest episode of mass death and displacement since the Nakba. The United Nations established the state of Israel in 1948. The ensuing Israel-Palestine war, which saw Israel fighting to expand its territory, kicked off decades of violence. Hamas’s heinous criminal attacks on October 7, 2023 can be understood as part of this broader narrative, rather than an isolated act.

I also thought it prudent to revisit Peck’s approach after screening Dror Moreh’s 2022 film “Corridors of Power.” Moreh’s film, which is powerful, affecting, and enraging, employs more traditional documentary tropes, in that it features archival footage and sit-down interviews with its subjects, and Moreh remains unheard, unseen. It is an examination of U.S. responses to genocide since World War II, featuring interviews with some of the most influential foreign policy members of past U.S. presidential administrations.

I could not shake the revelations sparked by former U.N. ambassador and secretary of state Madeleine Albright as she described a moment during the first Clinton administration when she was dispatched to Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Bosnian War.

“In driving through Sarajevo, I was just stunned that this kind of thing could happen. We’re talking about the nineteen-nineties,” Albright recalls. “Then the question is, how do you go back and not sound like a blithering idiot? Emotional. And I went back to the White House and I said, ‘I was in Sarajevo, where buildings had been bombed, where there were fires still burning and smoke coming still from a variety of buildings and people huddled on the street.Why should we not help people that also were living in a war zone that didn’t need to be a war zone?’

And I said something like, ‘gentlemen, history will judge us on this.’ They would say, ‘Don’t be so emotional, Madeleine.’”

“Exterminate All the Brutes” is a documentary unafraid to meet emotion with emotion, however, because Peck understands that the manipulation of emotions ranks among fascism’s most powerful and effective tools. And Peck is able to pinpoint emotional truths that arise in fictional work, such as Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” or Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and place them within the factual contexts from which they are drawn.

“As long as genocide, slavery, and the exploitation of human bodies do not converge into reparation—whatever the form—” Peck warns, “there won’t be any peace.”

Here, in the United States, which Peck notes, began as a colonial power, the backlash to 2020, to the possibilities for justice it briefly surfaced, continues. Moreover, that backlash has been institutionalized within the federal government, as a vainglorious dilettante secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth, blathers on about “no more dudes in dresses” and “pronouns” and attempts to purge from military libraries tomes that make sense and meaning of the very histories Peck is uniting in his film—tomes that might help elucidate the strange, sick irony of a military that “honors” the very Indigenous people it once annihilated by naming its missions and equipment after them.

Once again, Peck’s insights remain applicable.

“Everywhere in the world knowledge is being suppressed—knowledge that if known, would shatter our image of the world and force us to question ourselves—everywhere there, Heart of Darkness is being enacted,” he says. Knowledge is certainly being suppressed not just by the Trump administration, but in Gaza as well, in the form of scholasticide, but also the killing of nearly 200 journalists since Israel began its response to October 7. It continues to refuse outside journalists access to Gaza.

If we are to deliver ourselves from such darkness, though, knowledge alone is not enough to bring the light to drive it out. “It’s not knowledge we lack,” Peck concludes at the end of “Exterminate All the Brutes.” Rather, it is the moral courage to match emotion with action, lest we rationalize away what is left of our shared humanity and submit to a darkness we may fail, in our lifetimes, to escape.