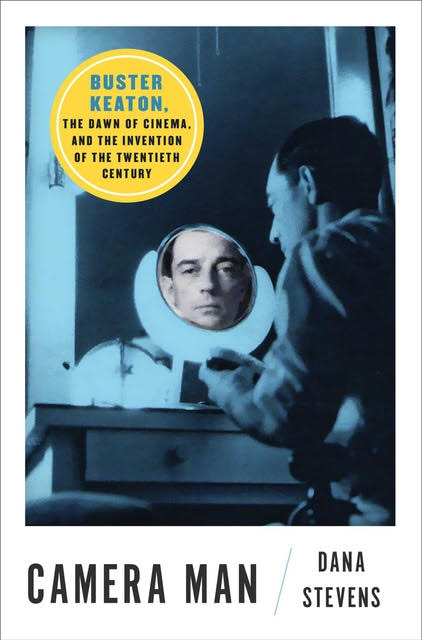

The splendid new book about Buster Keaton by Slate film critic Dana Stevens is more than a biography and more than a critical assessment of the work of one of the most significant and influential performing artists of the 20th century. Its scope is evident in its title: Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century. To cover this ground, Stevens deftly remixes the idea of the biography, which by definition focuses on a single individual and almost unavoidably implies a disproportionate picture of the subject’s significance. Her meticulous research and insightful depiction of Keaton’s personal and professional lives is one strand of the historical and cultural context she places him in. While some biographies claim a “life and times” approach, Stevens actually delivers, with enthralling descriptions of Keaton’s contemporaries, those he worked with and those who could be considered his competition, and with discussions of the changes in culture, show business, and technology as well as the fundamentals of cinematic storytelling he inspired and was inspired by. Stevens is an expert storyteller herself, taking on some of a writer’s biggest challenges, from vivid descriptions of the very elements of silent filmmaking that can seem outside the reach of words to finding just the right balance between admiration and sympathy for Keaton and candor about his failures and failings. Look how elegantly she compares two of his earliest works:

“‘One Week’ and ‘Cops,’ made two years apart, can be seen as companion pieces with opposing theories of the abyss. One proposes love as a potential, if fragile bulwark against the universal principle of entropy, while the other more bleakly posits Buster, and by extension all of us, as constitutionally and irrevocably alone. It’s only Buster’s undaunted perseverance in the face of chaos – matched, in ‘One Week,’ by Sybil’s – that lends the universe of these films moral meaning.”

Keaton’s career extended from turn-of-the-century vaudeville to his classic silent films, from the DIY of the earliest years of the movies to the rise and fall of the studio system. He was a part of the early days of television (he helped “I Love Lucy” get on the air and hosted a variety show). He was the focus of a film by legendary playwright Samuel Beckett and performed in a French circus. He appeared opposite Judy Garland and played “Bwana” in the 1969 Annette Funicello movie “How to Stuff a Wild Bikini.”

He wrote, directed, and starred in films that combined what he learned about comedy from performing in vaudeville since he was barely out of toddlerhood with his vision to push the new technology of moving pictures far beyond the limits of the stage. Viewed a century later, his films are still inventive and funny and his innovations are still reflected through all of the ways we watch media, from movies to memes to TikTok and doubtless to whatever comes next. His extraordinary contributions deserve to be described by someone who has the academic foundation for research that is diligent enough to be thorough and thorough enough to provide new information, the insights of someone grounded in the history of film and the way it is analyzed by scholars and critics, and, most of all, someone who is truly an exceptional writer, whose authorial voice is graceful, accessible and inviting, now and then appearing on the page to tell us how she connects to what she is describing. Stevens is superb in every category, and this instantly indispensable volume should have a place on the shelf of anyone who loves movies, comedy, history, critical analysis, or books that are a pleasure to read.

Stevens tells us that Keaton’s birth five years before the turn of the 20th century “was one of those times in history when the era that was passing and the one about to come seemed locked together like the teeth in a pair of gears, readying for the transfer of energy between them … [a time of] almost-but-not-quite modernity.” Queen Victoria still reigned. Women were a quarter century from having the vote. Entertainment was in vaudeville houses. Most relevant to Keaton’s early years, the legal and cultural understanding of child development was just beginning to shift from considering children to be pre-adults subject to whatever their parents or employers wanted to inflict on them to a category of human beings with exceptional vulnerabilities and potential that made it a matter of public interest to protect and educate them. Keaton’s father Joe, who made his tiny son the star of the family act by treating him like something between a punching bag and a football, was constantly evading the newly-established authorities.

Keaton came of age as the movies were just getting started. While some of his contemporaries transplanted their stage personas to the screen, Stevens shows us how Keaton jettisoned his over time, literally piece by piece in giving up the props that were part of his vaudeville routines. But he held on to the themes of a man struggling with the failures of the material world. His most famous moments involved gigantic props that could not fit on a stage like the house that literally falls on him in “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” (which lives on today as a popular gif) and the title train in “The General.” “For Keaton, every potential home is a space of danger and transformation; no façade stays standing for long … Not only buildings but cars, trains, boats, whole railway bridges show themselves to be as flimsy as theatrical scenery.” How much this must have resonated with a man whose home was wherever his family was performing, and how much the audiences were reassured by laughter in an era when the unprecedented transformation of the mechanical and material world had to be equally exciting and scary. Perhaps Keaton’s imaginative use of the camera and effects stemmed from his life as a performer, examining props like a table and a basketball to dream up ways they could be put to the most entertaining use.

Stevens gives us telling details—how a forgotten short film from the Ford Motor Company(!) was the almost-certain inspiration for Keaton’s second-made, first-released film as a director, “Home Made.” And she gives us the context—how the careers of Mabel Normand and Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle intersected and paralleled Keaton’s. (She also makes it clear that Arbuckle’s cancellation following allegations of rape was never supported by the facts determined at legal proceedings.) Time telescoped before me as I read that Joseph Schenck, who was Keaton’s brother-in-law and producer in the ’20s, was the same man who gave Marilyn Monroe her start in the ’50s.

She touches on issues of race and gender that foreshadowed central cultural, political, and legal conflicts that persist today, with evocative descriptions of major figures like Normand, Bert Williams, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, important here as counterpoint rather than intersection. She describes the shifting power centers in the entertainment industry as artists creating what interested them ceded control to (white male) money people who created what would sell and the ancillary enterprises that grew up around the movies, especially the nascent precursors to today’s extensive coverage of media and celebrity (including this site).

Today’s audiences have an opportunity unprecedented in human experience. We can only imagine what it would be like to watch the original productions of Shakespeare’s plays or to be able to hear what it was about Jenny Lind’s voice that made people willing to skip meals to buy tickets to her shows. But a century after they were created, we can see exactly what Buster Keaton’s audiences saw, though on screens Edison and Lumiere could barely dream of, and, with Stevens’ guidance, with greater perspective. We cannot imagine the shock of the audiences who saw the first moving pictures, who had to learn a new language of story-telling. I love Stevens’ description of the “destabilizing effect” of those early films on early audiences that today’s viewers seamlessly decipher as though they were some Chomsky-esque innate language. “For us,” Stevens writes, “the effect depends not on the shock of seeing everyday life reproduced on a screen but on these first films dissimilarity from our daily lives, the incredible expanse of time and change that separates then from now and us from them … moving most of all for its unpolished, unscripted specificity.”

I would have finished this book in two sittings but I could not resist stopping to check YouTube to watch some of the films Stevens describes so invitingly. While I was a Keaton fan already, I was grateful for her guidance in pointing out details of note, either because they were indications of his innovations or of his development as a director and performer. She shows us how his influence is seen in the work of Jackie Chan, Edgar Wright, and dozens of people on TikTok. Best of all she inspires us to return to the original, which we can enjoy just as our great-grandparents did.