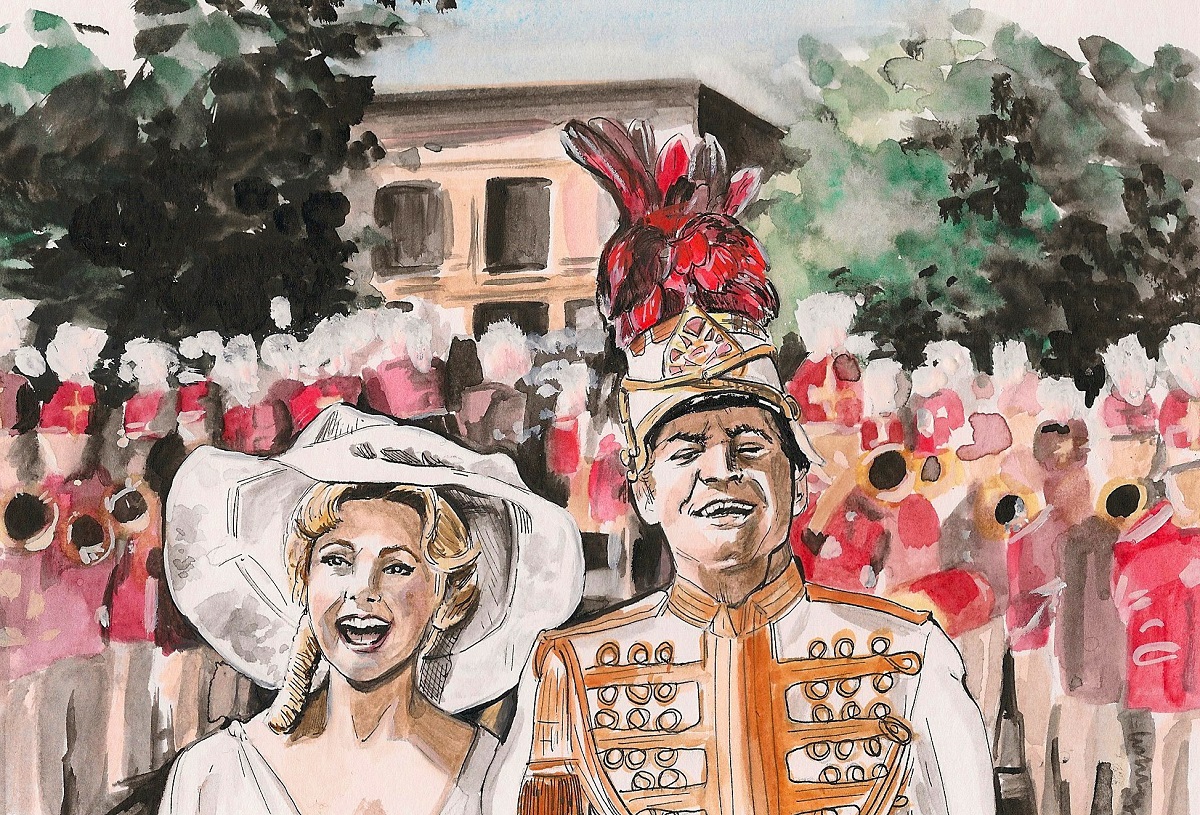

The wonderful people at “Bright Wall/Dark

Room” launched their February issue today, and it focuses on music,

including essays on “Nashville,” “Moulin Rouge!,” “The Sound of Music,” “Velvet

Goldmine,” “Evita,” “The Court Jester,” “We Are the Best!,” “Tous les matins du

monde,” and “The Music Man,” which we’ve excerpted below. Read more excerpts here and you can buy the magazine on your iPhone

and iPad here or sign up for

the web-based online version here. The illustration above is by Brianna

Ashby.

My father cries at parades. Especially at the

small town variety in which scouts march behind banners made of top sheets and

a junior high school band goes by in a clatter of excessive snare drums. At

these events there is usually a moment, at least once, when you can catch him

wiping away a few tears, grinning.

I spent half my childhood in a small New England

town whose top three claims to fame are all Revolutionary War landmarks, so the

opportunity to glimpse my father crying at parades while a piccolo whistled by

came at least a few times a year. There were other events that had this effect

on him too, mostly community theater productions, sometimes the Thanksgiving

Day high school football game. As a child, I mostly found it amusing that we

could giggle as a family at the parade-crying phenomenon – it made for a

comforting family shorthand, a way to demonstrate that we all knew each other

well. I also didn’t “get” it, and will admit that the parade-crying made me

slightly nervous, in that way one feels when one’s parents’ suddenly

demonstrate a mysterious interior life. I didn’t know what it was that could

tap so deep a well in my decidedly not weepy or wimpy dad.

It’s always been clear to me, though, what those

spectacles had in common: People practicing hard to get where they were.

Everyone in it together. And of course, music.

*

I knew that The Music Man (1962)

was Dad’s favorite film long before I’d ever seen it, which finally happened on

a day spent home from elementary school with a fever, swaddled in an afghan

with ginger ale and soup on a card table next to me. Though I’d heard him quote

it often, I had never been particularly drawn to the storyline. But a sick day

was an opportunity for Dad to give me some assigned viewing, and musicals were

a comfort to me. For years, just about the only movies I watched were Mary

Poppins and Peter Pan, both of which had been recorded for me by my

grandfather on an old VHS tape when they aired on TV. That tape became an

object both beloved and full of love, as I wound and rewound it over and over

again, never even skipping the commercials, as they too were part of the joy.

When people groan about musicals, as I’ve

discovered many of them do, they often drop the accusatory phrase: “And then

suddenly someone just bursts into song.” The complaint seems to be that

this feels inauthentic somehow, that it actually pushes the viewer away from

the story and into the role of skeptic. That things just don’t happen that way.

And yet time and again, upon winding and

rewinding, they do.

The Professor sells marching bands. He rolls

into places that are plagued by what plagues us (“River City ain’t in any

trouble,” says his friend when the professor first appears in the small Iowa

town to ply his trade. “Then we’ll have to create some,” he replies) and offers

a solution to all the town’s woes in the form of music, choreographed marching,

and sharp uniforms. Please observe me if you will, he says, I’m

Professor Harold Hill, and I’m here to organize a River City Boys’ Band.

After the Professor has instilled his

foundational fear in the townspeople and gathered them up to sell the cure, he

abruptly transitions away from singing of his phony credentials in the put-put

cadence the musical opens with (a beat that forges ahead through the entire

score, connecting one place to another like the train it emulates). Suddenly we

have a drumline’s rhythm and a brand new song, already familiar to me on my

convalescent couch — a story in the past tense, sung with the kind of

dreamy-eyed wonder than can only be found imbued in memory. The Professor

recalls — performs, really — the first time he heard this music: a day when

the greatest names in marching band history came to his town when he was young.

And so we’re dropped, right into that awe:

Seventy-six trombones caught the morning sun

With a hundred and ten cornets right behind…

*

There’s something about live music, more so than

other art forms, that makes me feel deeply impressed, the grandeur and power of

what people can do in groups displayed at its finest. I get this feeling

whenever a chorus sings in five harmonious parts, or a symphony saws away in

unison at a piece of centuries-old music: the feeling goes, we humans created this?!

Whether I find the music itself enjoyable or interesting is a separate matter.

It’s like standing on the steps of a cathedral; that it is a feat is

undeniable.

I can’t say I find parades to be such a feat

themselves, but I will allow that there’s something deeply impressive about any

group of people coming together and coordinating something so easily verging on

chaos. And there’s something uniquely moving in the air when they do it out of

joy, even if that joy is not exactly projected by sweltering adolescent

clarinet players. A parade is a joyful act, and it sort of flies in the face of

logic with its ultimate awkwardness.

Musicals, too, are often awkward. They’re such a

staple of high school life and community theaters that most attempts are doomed

to be mild and endearing catastrophes right from the start. That they can also

be performed expertly—without a seam showing, and with perfect pitch throughout

and set changes that barely rustle—only makes our stumbling through them in

auditoriums a few times a year all the more lovely.

The Music Man is about a marching band that cannot play, as so many plays and

parades and sporting events are about people who cannot fully do the thing that

they are there to do. But oh, what pride there is inherent in the trying.

*

When I was fifteen, I made my first and best ever

mix CD. I dubbed it, in self-conscious Sharpie lettering on its grey grooved

surface, “The Happy Sad Mix”. I remember explaining the title as “songs that

make you so happy you get sad, or so sad you’re kind of happy.” While

everything about this now makes me cringe with the fifteen-ness of it all, I

still stand by every track, and can’t imagine a more apt title. These songs

provoke the same feeling in me today, with the added wistfulness of remembering

those hormone-flooded late nights of CD burning, feeling like the only person

in the world who was still awake, the precise person to whom my music really

spoke.

I suppose that nostalgia is a word that could

more efficiently explain “happy sad”. But if nostalgia is the word for it, it’s

qualified by the fact that, to me, the particular nostalgia provoked by music

that I’ve loved is usually an ache for something that never was, or at least

something I have never actually experienced. This feels particularly true when

remembering the music of my teenage years – sentiments I would sing and quote

and copy into notebooks with the deep resonance of someone who had been through

much more heartbreak and sorrow than I ever did in my first couple of decades.

I went through a decent amount of both, but somehow I felt that the versions of

longing and loss described in those song lyrics were truer than the ones I

lived. So I joined my voice to the chorus and mourned all sorts of people and

places that I had never known.

Portuguese has an achingly beautiful word, saudade,

a not-quite-translatable longing for something that is gone and may or may

not return. It’s the “may or may not” that seems to defy translation – a part

of the definition that isn’t frivolously wordy, but rather contains the

ambiguity and wonder that is so key to the feeling.

In other words, the thing that separates saudade

from nostalgia is hope.

*

I must admit: the allegation that musicals are

inauthentic puzzles me. What I get in those bursting-into-song moments is more

like an overwhelming feeling of feeling. When sung, especially when sung by

many people all at once, everything that feels big suddenly becomes big.

It fills my stomach as it fills the room. It tugs at me in a familiar way.

It’s the feeling of late night, teenaged emotion

and yearning, and a palpable connection with the sound in one’s headphones, the

feeling that words written decades ago are coming from some place deep in one’s

own gut.

It’s the feeling of being a part of a group that

has worked hard and built something bigger than its members.

It’s the feeling of standing on the sideline of

a small-town parade and knowing — maybe not knowing personally, but somehow

knowing — all the people in it, and clutching one of those little flags

they hand out, and being there with my dad.

These moments of sudden music are actually

exaggeratedly authentic, so real that they’re nearly unrecognizable as the

inner monologues we go to such lengths to mask and keep inside at those times

in our lives when we just want to burst.

*

But nostalgia has its negative connotations,

too. The essayist Michelle Orange writes that “What we call nostalgia today is

too much remembrance of too little.” This accusation stings a bit for those

prone to the feeling, though most of us will quickly point it out when someone

more conservative lashes out against change and demands a return to purity,

order, and manners.

To sell his bands, the Professor must first sell

the idea of going back to a Golden Age that we know from the beginning probably

never existed. We know that he can’t teach music, and that he’ll never teach

anyone to march. We know that the people of River City are ridiculous for being

so easily mongered into fear, and for believing that they can ever buy back the

past. We also know that the past cannot possibly have been so golden, that it

was in fact a time of dust bowls and slavery and great depression.

We know and yet as we watch we yearn for the

promise of a band to be true, even while we hope that The Professor will be

caught red-handed and leave the people of River City to their changing times.

And then he starts to yearn for it to be true,

too. To lock down a girl, sure (there’s that going on, which I haven’t

mentioned, but you must have guessed) but also because, after all this time

hearing the story coming out of himself and filling the room with sound, he

wants to be able to touch it for once. His performative nostalgia turns into an

against-all-odds hope. Without realizing it, he had been joining his voice to

the chorus, joining River City in yearning and hoping for a time that he’d

never known either, though he’d sung of it so many times before.

*

This, then, is what musicals can do: they give

us a chorus of happy sad mourning for something none of us have experienced and

for which all of us are nostalgic, this version of the world in which people

burst open and beauty comes out.

At some point in my mid-twenties I started to

cry happy sad tears on a regular basis for the first time. It still makes me

feel refreshingly adult, like how I also acquired a taste for olives. It makes

me feel grateful that my dad showed me that crying at parades, or your parade

equivalent, is part of being a grown up—the more simple beauty you’ve seen in

the years you accumulate, the more it bowls you over. Now, the happy sad

feeling seems less like teenaged angst and more like a side effect of the

accumulation of wonder. Some of the wonder I’ve accumulated I’ve experienced –

no, all of it I have, in one way or another. How wonderful. How deeply

impressive, that we’ve experienced all that.

There were copper bottom tympani in horse

platoons

Thundering, thundering louder than before.

Double bell euphoniums and big bassoons,

Each bassoon having its big, fat say!

Horse platoons! Who

knows. What’s important is that this is a mighty return, an eternal reprise, a

dialogue with the past. It’s as if every song is lined up in front of another.

It’s as if we’ve been doing this forever, as if we keep getting better. At

making music. At being human. Thundering, thundering, louder than before.