Editor’s note: In the new book “Roman Polanski: A Retrospective,” James Greenberg combines interviews with Polanski and the people who worked with him with close attention to the films and critical reaction for a compelling film-by-film examination of Polanski’s career (published by Abrams Books).

For those in or near New York City, on Oct. 25 at 1:30pm, James Greenberg will be at a screening “Knife in the Water” and three shorts as part of the “Auteurist History of Films”

series at the Museum of Modern Art. On Oct. 26 at 2pm, he’ll introduce a screening of “Repulsion” at Museum of the Moving Image.

In this excerpt, Greenberg looks at “Rosemary’s Baby.”

Buy “Roman Polanski: A Restrospective” at Amazon and B&N.

Rosemary’s Baby 1968

Ever since he was a teenager, Polanski imagined how he would turn a novel he was reading into a movie. With Ira Levin’s supernatural potboiler Rosemary’s Baby, he got his first chance to do so. It marked his inevitable arrival in Hollywood, and at thirty-four his coming-of-age as a world-class director. He couldn’t have been happier.

Initially, however, Polanski was lured to Tinseltown under somewhat false pretenses. “Robert Evans [Paramount head of production] called me with a proposal for a skiing picture, ‘Downhill Racer,'” Polanski remembered. “And since skiing is my sport and I’ve always been eager to do a film about it, I came and he handed me the script and also a bunch of long strips of pink paper which were the proofs of a book called ‘Rosemary’s Baby.’ He said, ‘Read this first please.’ So I went back to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where I was staying, and started reading it, and around four in the morning I was still at it. The next day I came back to the studio, and said, ‘OK, I’ll do it.’ And that’s how it happened.”

Polanski immediately saw the cinematic potential of Levin’s tale of a young, innocent wife in New York whose husband sells their baby to a pack of Satan worshipping witches in the next apartment. He was so excited by the project that he went back to London and in a marathon session dictated the script to his secretary in three weeks, returning to Los Angeles with a 260-page first draft.

“Rosemary’s Baby” is still a very scary film because Polanski completely understood the book and what he needed to do with it. The originality of his concept was to present supernatural events in a real and believable way. What made the story shocking was that Rosemary was a vulnerable girl from Omaha living an everyday life in the big city that little by little goes haywire. In the context of the film, it was something that could happen to any unsuspecting soul.

This was gold for Polanski, who in his best films has taken ordinary people and magnified their worst nightmares: Jake Gittes is drawn back to Chinatown against his best judgment; with no apparent survival skills, the hero of “The Pianist” is thrown into a war-ravaged world and forced to survive. Just like that, life can take a wrong turn and become dangerous. For Polanski, existence has always carried a sense of dread. That’s why he’s naturally so good at building suspense. When I asked him how he does it, he said, “It’s just there … If I have some kind of facility in creating suspense it comes from life and the various things that I may have gone through for real.”

In “Rosemary’s Baby,” Polanski wastes no time setting up a disquieting tone. The credits roll with various benign bird’s-eye views of New York, but as the camera closes in and it’s time to begin the story, a conventional overhead shot of an ornate apartment building (the Dakota on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, called the Bramford in the film) is slightly off kilter. It’s at an odd angle, a bit woozy and vertigo inducing. On top of that, Mia Farrow is humming the film’s haunting theme in the background, as if casting a spell.

Even when Rosemary (Farrow) and her actor husband Guy (John Cassavetes) are happily looking at the apartment, there is an uneasy feeling. And with the great, jittery character actor Elisha Cook, Jr. (the gunsel who Bogart slaps around in “The Maltese Falcon“) as the renting agent, it’s a good bet that something is wrong with the place.

But to set up the ghastly events to come, Polanski made everything around them seem normal, including the supporting cast. In those days he would sketch what the characters looked like in his mind’s eye and give it to the casting people to bring in possibilities. He wound up casting a harmless-looking bunch of Hollywood old-timers who are pitch perfect. Sidney Blackmer and Ruth Gordon play the next-door neighbors, the elegant patriarch Roman Castevet and his dotty wife Minnie. Patsy Kelly is the none-too-bright upstairs neighbor Laura-Louise. And central to the plot is Ralph Bellamy, who exploits the wholesomeness he had built a career on, as the prominent New York obstetrician Dr. Sapirstein. All of them witches.

The character of Rosemary described in Levin’s book was a robust, all-American girl, so Farrow was initially not even on the radar as Polanski met with every prospect on the Paramount lot. At that time, she had some notoriety as the star of TV’s “Peyton Place” (and as the wife of Frank Sinatra), and when Polanski met with her he was taken with her naturalness (she painted flowers and wrote the words “peace” and “love” above her dressing room door). He liked that Farrow had none of the Method “trickiness” about her and played things straight. Her slightly spacey, helpless quality made her seem like the perfect sacrificial lamb at the altar of her husband’s ambition.

For the role of Rosemary’s opportunistic husband Guy, Polanski settled on the New York actor and director Cassavetes. Perhaps fittingly given the nature of the material, it was not a marriage made in heaven and ultimately these two strong-willed men of opposing sensibilities did not get along. As a director, Cassavetes was freewheeling and improvisational, where Polanski was precise and methodical; as an actor, Cassavetes was Method trained while Polanski preferred a more naturalistic style. Polanski was never entirely satisfied with Cassavetes’ performance, but I think he underestimates its effectiveness.

This is a deeply despicable character. As an actor whose career is going nowhere he thinks nothing of offering his wife to the devil in exchange for success. His hunger for fame, as relevant today as it was when the film was made, is what really drives the plot. Not surprisingly, next stop for him is Hollywood. Whatever his method, Cassavetes was convincingly able to capture the character’s shallowness and self-absorption.

Polanski had no trouble adapting to the Hollywood system. “I felt very much at ease and even if I had to experience a new type of work because it was a studio picture, I felt very comfortable,” he recalled. “I even remember driving through the Paramount gate on the first day of shooting and thinking I don’t have any of the butterflies that you usually have.”

For the first time, Polanski felt that he totally knew what he was doing on the set and was in full control of the medium. He was getting paid $150,000 as the director, more than he made on all of his previous movies combined. But perhaps more importantly, he was working with a then-sizable $2.3-million budget and a crew of sixty first-rate technicians. He was intent on making the most of the resources he had at his disposal. Ever since he had seen Elia Kazan’s “Baby Doll” when he was in film school, Polanski had admired Richard Sylbert’s production design. The two men met in London while Polanski was making “Repulsion,” and Polanski said he hoped to work with him someday. Until “Rosemary’s Baby” he could never afford his salary, but once he was in Hollywood, Sylbert was the first person he hired, even before the cast.

As an inveterate New Yorker, Sylbert was an ideal choice. “Roman didn’t know New York,” recalled Sylbert in a 2000 documentary about the making of the film. “I spent thirty-five years there. There’s not a place in the book that I didn’t know.” Perhaps his greatest contribution to the film was the interior set for the Dakota apartments that he built on the Paramount lot. The mid-sixties modernism of Rosemary’s apartment and the Old World Gothic of the Castevets’ place next door set the perfect tone for Polanski to stage these terrifying events.

Sylbert said that Polanski knew more about lenses than the cameraman, but the great cinematographer William Fraker, who went on to garner five Academy Award nominations of his own, was no slouch. In an interview for the 1992 documentary “Visions of Light,” Fraker gave some insights into how Polanski worked on the set. For a shot where Ruth Gordon is seen talking on the phone in Rosemary’s bedroom, Fraker set up the camera in the living room looking through the doorway (a typical Polanski set up). Fraker framed the shot so the audience could see Gordon sitting on the bed. Polanski came to the set and said, “No, no, move the camera to the left.” Fraker said, “But then you won’t be able to see her!” Polanski said, “Exactly.” So Fraker shot it with just Gordon’s back visible. Later when he saw the film with an audience in a theater he understood why. Eight hundred people tipped their heads to the side to try to see Gordon around the doorjamb. And that’s how Polanski grabbed the audience and pulled them into the action.

The film is full of directorial touches like this that add to the mood and help build the suspense. One of my favorites occurs late in the film, when Rosemary has more or less figured out what’s going on and she is in a phone booth on a busy street. As she frantically waits for her original, good doctor to call her back, she sees the back of a white-haired man who looks exactly like the now sinister Dr. Sapirstein pacing outside the booth. It’s a blistering hot day and there is very little happening in the frame, but the suspense is intense as Polanski makes viewers feel the stifling heat and fear. Turns out it’s just a guy waiting to use the phone.

Probably the most talked-about scene and the one that sent people home with nightmares of their own was the dream sequence in which Rosemary is raped by the devil. Polanski wanted it to look the way we experience dreams in real life, not in movies. “I was trying to use the things that I remember from dreams, which is, one, that they are very quiet, almost silent, even if somebody is screaming. And, two, that people change. The person you’re dreaming of is suddenly not the person you started the dream with, but has somehow evolved into somebody else. Those are elements I was trying to sell in those sequences.”

The scene begins with Rosemary bobbing on a bed in a body of water, like a waterbed adrift in a lake. A clock loudly ticks off the seconds to intensify each moment. As all the neighborhood witches stand around naked muttering what sounds like dissonant Gregorian chant, Rosemary’s husband mounts her. But then Polanski cuts to a pair of scaly, webbed hands dragging across her body. She looks up and sees the catlike eyes of the devil, or thinks she does. What makes it even more terrifying is that at the height of it, Rosemary wakes up and screams, “This is no dream, this is really happening!”

Or is it? The story is told from Rosemary’s point of view, but what if that’s unreliable? At least, Polanski wanted it to be open to interpretation. As a confirmed agnostic, he did not believe in the devil any more than in God. “That aspect of the book disturbed me,” he said. “I could not make a film that is seriously supernatural. I can treat it as a tale, but a woman raped by the devil in today’s New York? No, I can’t do that. So I did it with ambiguity.”

For the sake of credibility—and his own worldview—there had to be the possibility that the whole thing is a figment of Rosemary’s imagination. This was especially true of the ending, in which Polanski refused to show the baby, although it was described in detail in the book. “Better to leave it obscure and ambiguous,” he said. “It doesn’t all have to be so obvious. The obvious is boring.”

When the film came out in mid-1968—it was a huge hit—people would come up to Polanski and insist they had seen the baby, cloven hoofs and all. But all that’s there, and only for a split second, is a subliminal superimposition of catlike eyes. When I told him I was one of those people and for years believed I had seen the baby at the end, he seemed pleased that he had fooled me. “You thought you did? Well, that’s good. It shows that you can act on the imagination of the spectator; you’re creating certain illusions. In a film like this you have to be mysterious.”

I don’t think anyone—except for a few crazies—truly believed Rosemary had been violated by the devil. But the important thing is that for two hours Polanski made it feel like it could happen. And in his great films, of which this is surely one, there is always that shadow of a doubt.

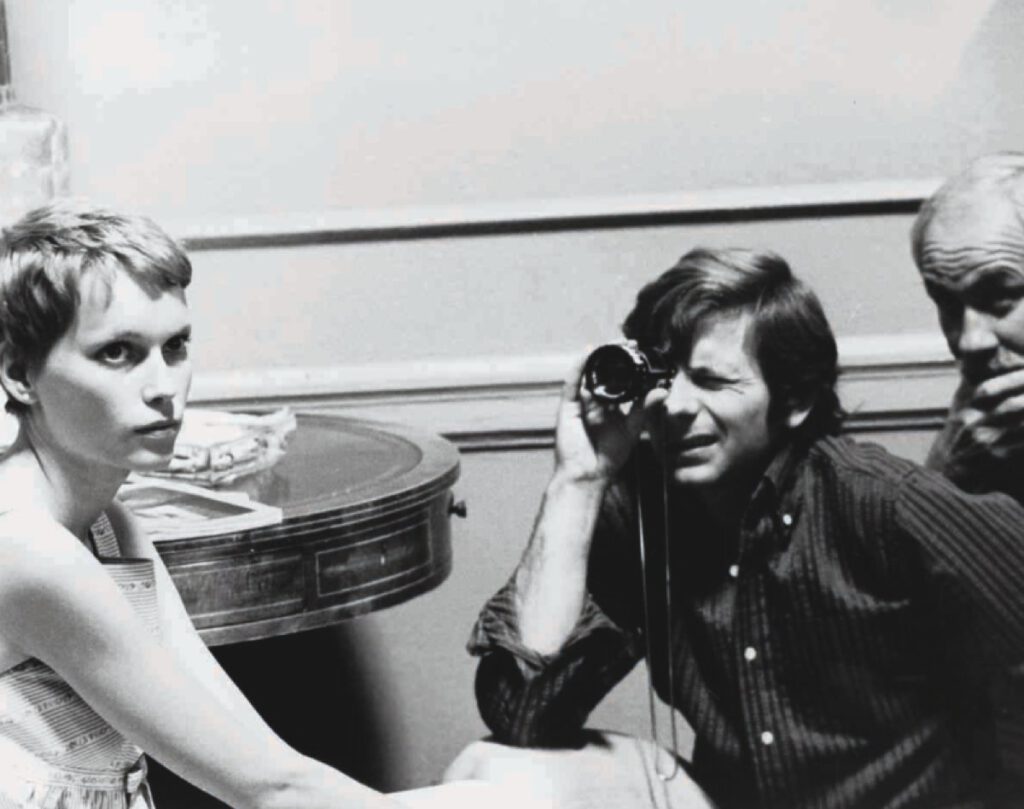

Photos: © Photofest (Paramount/Photographer:Robert Willoughby)