The first time we meet Martin Crane in “Frasier,” he is supremely grumpy. An army vet, Martin has been forced to retire from the Seattle police force due to a gunshot wound to the hip. Unable to properly care for himself, he moves in with his estranged therapist son, Frasier, his total opposite. When Frasier overdoes the welcoming pleasantries and compliments him on how great he looks, Martin replies: “Don’t B.S. me, I do not look great. I spent Monday on the bathroom floor. You can still see the tile marks on my face.”

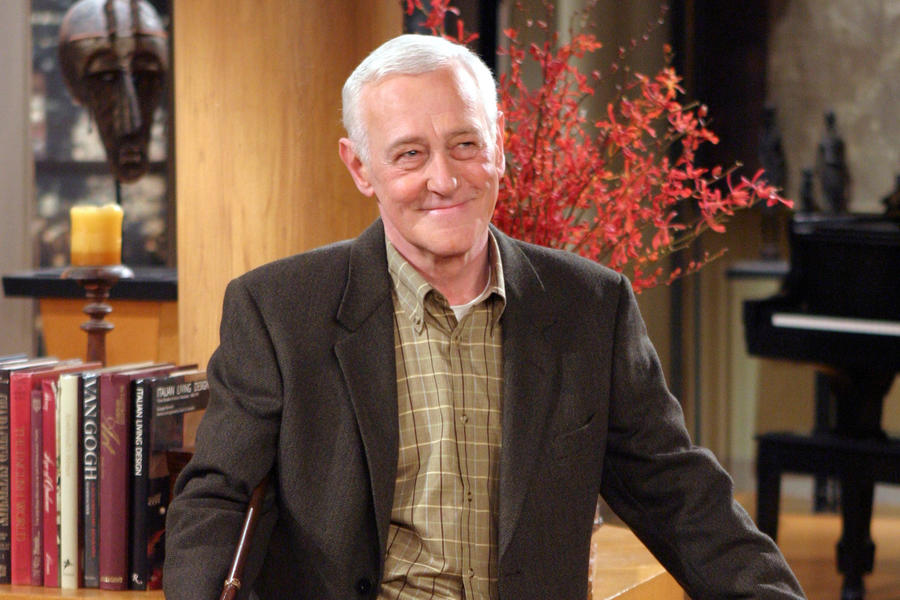

At this formative point of the show, Martin is an audience surrogate. For Frasier (Kelsey Grammer), and his brother Niles (David Hyde Pierce), smug pomposity is the central source of comedy, and their dad is there to play straight man to their ridiculous antics. Over the following eleven seasons, though, Martin grows out of being a foil and into a fully-formed character—this had as much to do with the terrific writing as with John Mahoney’s memorable, delightful, superb portrayal of the Crane patriarch.

If Frasier had one underlying theme, it was reinvention. And most of the time, this reinvention was forced upon the characters, instead of being a comfortable choice. Frasier had recently divorced and left Boston to start a new life in his hometown. Suddenly, he found himself having to lodge with his ailing dad. Martin, having lost his wife a few years previously, was still hanging on to his job as a police detective when he stumbled upon an armed robbery that practically crippled him. The show carried this theme further with the other lead characters in later seasons: Niles was stuck in a loveless marriage that nonetheless provided him with material comforts when his love for his dad’s physical therapist, Daphne (Jane Leeves), eventually made him relinquish it all. Daphne, of course, was an immigrant in the United States, having escaped from a violently dysfunctional family. Even Frasier’s producer Roz (Peri Gilpin), a proud bachelorette and the most well-adjusted of the main cast, had to open a new chapter as a single mother following an unplanned pregnancy. Grappling with limitations, regrouping, and then forging something new and good was a central aspect of Frasier. Essentially, then, it was a show about second chances: the ones we make and the ones we are forced to make.

Perhaps this was why John Mahoney fit so perfectly as the moral core of “Frasier.” Giving everything up, throwing caution to the wind, and starting all over again is easier said than done. Especially after the wide-eyed days of youth. Yet that’s exactly what Mahoney did. He was originally from England, but came to the United States when he was 19. Desperate to fit in (“I was never a non-conformist” he once said in an interview), he joined the army to expedite the naturalization process, lost his Mancunian accent, and eventually moved to Chicago. Discontent with his life as a medical journal editor, he eventually gave that up, too, in order to pursue acting. He was almost 40.

“I had plans too, you know! And this may come as a shock to you, sonny boy, but one of them wasn’t living with you,” Martin tells Frasier in that first episode. It’s a very moving scene that ends with Frasier beseeching his dad for a simple “thank you” for taking him in, which his dad eventually affords him first, in a roundabout way, at the end of this episode, and then, much more directly, the end of the show eleven years later. Between those two “thank yous,” Martin truly evolves.

But there are a number of constants, like his physicality. Whenever Martin sits himself down in his infamous chair (filthy, ugly, and in complete contrast to the rest of the apartment), Mahoney arches his back slightly, almost pushed down by the weight of the world and his experiences, his losses. Mahoney was only fifteen years older than Kelsey Grammer, but he chose to play him as a visibly elderly man—in his mannerisms, his reactions, his movements. Death is a palpable presence in Martin’s life: In the season one episode, “Give Him the Chair,” he mentions how much he misses his dead wife, still dreaming that she would come to wake him up when he fell asleep in his chair. In season five’s “The Gift Horse,” the boys buy Martin his old horse from his days as a mounted patrolman. Martin’s subdued reaction eventually leads them to the stables where they find their father talking to his old buddy: “We were something, weren’t we? Now they’re putting you out to pasture and I’m riding the buses. It’s fun getting old, isn’t it?” In “Deathtrap,” from Season 9, Martin talks to Roz’s daughter, Alice, about death, her hamster having recently passed on. Alice scoffs at Martin, when he insists Eddie, his trusted ten-year-old canine companion, is only a puppy. When she and her mother leave, Martin calls Eddie, a visibly elderly dog, to his lap, holds him tight, and plants a gentle kiss on his head.

Perhaps Martin Crane’s most solemn moment in the show comes in the eighth season’s “A Day In May,” when Martin goes alone to his shooter’s parole hearing. He speaks courteously with his assailant’s mother. During the hearing, the culprit is contrite, but Martin cannot bring himself to express forgiveness—and parole is denied. The look John Mahoney gives the shooter and his mother is complicated, and with another actor, and in another show, it could have easy been one note. Mahoney elevates it to greatness.

It would both be unfair and greatly specious to merely highlight such sober moments. “Frasier” was a sitcom after all—true, it was more eager, and even more successful, than many other sitcoms to play with a spectrum of emotions. However, even though its raison d’être was to make people laugh, the sitcom’s emotional core was about the eleven-year long journey taken by the Crane men to become a family again. Frasier, Niles, and Martin are all too happy to be remain relative strangers at the beginning of the series—slowly, over the course of the show, they excavate their affection for each other like a buried treasure chest.

In season one’s “Travels with Martin,” Frasier laments the close relationship Roz has with her father when she suggests they spend more time together. “Are you forgetting that my father lives with me? How much more time together could we spend,” he replies. Eventually, they decide to go on a road trip, but both Frasier and Martin ask for Niles and Daphne, respectively, to come along with them, arguing the father and son have nothing to talk about. When Martin eventually admits it to Frasier, there is real pain and frustration in his voice: “When we’re alone together, I just don’t know what the hell to say.” A flashback episode at the end of season three, “You Can Go Home Again,” showing Frasier’s first days back in Seattle, ends with Frasier and Martin watching television in complete silence as if they are confined to two soundproof booths separated by an invisible wall.

Little by little, scene by scene, episode by episode, their relationship grows. Kelsey Grammer and David Hyde Pierce, exceptional actors both, had full command of their craft, but the real growth comes from Martin. John Mahoney plays him as a relic in those formative episodes. In the second season’s “Breaking the Ice,” he can’t bring himself to say “I love you” to his kids, something he readily dishes out to his drinking buddy and his dog. When his sons make a fuss about it, as they always tend to do, Martin eventually bursts out: “Well, did it ever occur to you to say it? You know, your mother used to get all over me about not saying stuff too.” The men of his generation never spoke about such trivial issues like “love”: And Mahoney’s portrayal of Martin imbues the character with regret as he tries to find a connection he never thought he had with his kids.

A ninth season episode, another flashback, this time to the day Martin got shot, shows how Martin is slowly working through his regrets. Scenes from Martin’s last day as a cop are juxtaposed in the present day with his first day as a security guard. He spends the former whining about Frasier and Niles to his partner, eventually concluding that he should call them out of the blue when he got home. And then life happens and he finds himself in hospital. When a distraught Niles comes to visit Martin to tell him he’d never understand how his father could take his risks, Martin replies, hurtfully: “No, you probably won’t.” Back in the present day, his kids are squabbling about who will take Eddie for a walk when Martin is away at work. Exasperated, he calls them over to him. The boys sheepishly shuffle over to their dad, back to being five year olds both, and are shocked when their dad kisses them both on their cheek to say: “I’m going to work now. I’ll be home late. Don’t wait up.”

Martin’s love for his boys is slowly revealed over the show, but John Mahoney refuses a maudlin or prosaic approach to his character growth. In the seventh season episode, “Out with Dad,” Martin ends up having to pretend he’s gay in order for Frasier to have a chance to woo his latest flame, Emily, who introduces her queer uncle, Edward, to Martin as a potential suitor. It’s a bit awkward at first, but the two men eventually bond over their sons. “I’ve let Frasier drag me to all kinds of places I didn’t want to go to, just so that I could spend some time with him,” Martin says, now much more comfortable. When he decides to drive Edward home in order to give Frasier and his date some alone time, Emily says: “It was so sweet of your father to do that. He really loves you, doesn’t he?” Frasier replies, “You have no idea.”

In these later episodes, even in such situations where Martin has to do something he is not naturally good at or willing to do, the character’s unpretentious decency and good humour come through. He seems to genuinely like all the other characters even when he is having differences with them. That it’s impossible to say if that was John Mahoney or John Mahoney playing Martin Crane is probably ultimately creditable to him. He manages to move seamlessly from genuine heartbreak, like when Frasier dislikes his gift of a gaudy painting in “Our Father Whose Art Ain’t Heaven”, to sheer joy, as when his sons produce a song he wrote for Frank Sinatra, in “Martin Does It His Way.”

All this culminates perfectly in the show’s final season, its glorious swansong. In “BOO!,” as Martin is proposing to his girlfriend in the hall, Frasier and Niles have the sweetest conversation in their dad’s room while going through his stuff:

Frasier: God, what pains we were. Didn’t want to get our hands dirty, didn’t want to go fishing, didn’t want to sleep on the ground. But he kept taking us, year after year, just so he could spend time with us.

Niles: And frighten us to death with stories of hook-armed slashers.

Frasier: You know, no matter how frightened I got, as soon as Dad started laughing again I knew that everything was safe. You know, I’m not ready to lose him, Niles.

Niles: Me neither. And I don’t want my child to miss knowing him. Who else is going to teach him how to catch a football ball?

Frasier: You know, eleven years ago when he moved in here, I couldn’t imagine a bigger infringement on my life. Now, I can’t imagine my life without him.

The show’s finale, “Goodbye, Seattle,” finds Martin moving out of the apartment, as Frasier gets ready to leave Seattle (the location is a surprise so I shan’t spoil it). Earlier in the episode, a delivery man comes over to remove Martin’s armchair from Frasier’s apartment. While wheeling it out of the door, the mover smashes the chair to the wall. “Be careful with it,” Frasier says. Later, as Martin is saying goodbye to his son for the last time, he holds Frasier and, barely holding back his tears, says, “Thank you, Frasier. For… well, you know.” The Martin of the first episode could not even grant his son “one lousy thank you.” But, having made his son wait for 11 years, Martin’s thank you is that much more meaningful and earnest than anything Frasier could have asked for.