Phillip Noyce‘s “The Quiet American” is a tale of lies. It introduces itself as a noir murder mystery, but seamlessly veers into a story of man in love with a dancer, looking for redemption in his twilight.

Phillip Noyce‘s “The Quiet American” is a tale of lies. It introduces itself as a noir murder mystery, but seamlessly veers into a story of man in love with a dancer, looking for redemption in his twilight.

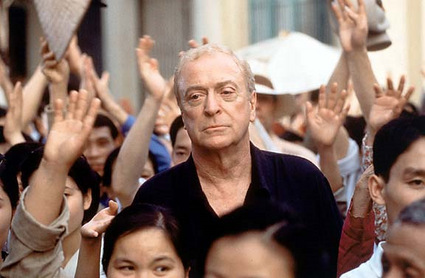

From there it flows into a love triangle pitting an old frightened Brit (Michael Caine) against a young fearless American (Brendan Fraser). In moments of crisis, the American saves the Brit’s life. In a moment of anger, the Brit seems to allow the American’s death.

“The Quiet American” can be viewed on Netflix Instant.

Or, maybe it is the account of a British journalist looking to invent a great story, accidentally discovering an even greater scandal, while coincidentally meeting the young naïve American he mentors in every corner he looks. And, with each subsequent meeting we learn that the Brit sees in the American the man that he himself was, the man he wishes he was not, the man he is, and the man he wishes he is not. And, with the American’s death, the Brit frees himself from himself.

So, maybe it is a story of people who refuse to be honest with themselves. These are characters whose loneliness compels them to stare longingly toward the outside world, not noticing the lovers within their chambers. Everyone in this movie seems to look out a window or into a window, locking eyes with someone long enough to have a full, expressionless conversation. When they speak, through cordiality or confrontation, they contain themselves with spoken pleasantries, though their eyes fire caustic beams of rage. Their tongues do not reveal what their hearts really feel. But, do they even know what their hearts feel? So, when the man is murdered and the methods are revealed, we still do not know the motives, because the murderers themselves might not know.

Or, maybe it is a tale of espionage. Journalists, physicians, generals, dancers, and assistants, twist their inconsistent moralities to support their single-minded personal interests. In the foreground of this tale are the White Imperialists – British, American, French, Soviet – grappling on the wrestling mat that is the colorful nation of Vietnam and her people. The murder that begins and ends the film is not an act of betrayal, but an act of revenge on behalf of an exploited society. The murder is just another act of war.

In that foreground, Thomas is an aging British journalist who drinks his tea on schedule and offers people their courtesies. Alden is a youthful American who celebrates American democracy, dresses a bit too formally, and takes offense at improper behavior. Thomas’ baggy eyes have witnessed the horrible depths of the human heart, often through his own misconduct, leaving a trail of ignored victims. Alden’s upright posture dreams of saving souls through the promises of the New World. The two meet at the quickstep of Thomas’ two mistresses: a young taxi-dancer named Phuong, and her home country, Vietnam. Thomas sees in Phuong and Vietnam a refuge from the demons he hoped to leave in England. He hopes for salvation without seeking forgiveness. Alden sees victims he hopes to rescue and provide refuge, even if he has to steal them, from Thomas.

Though Caine’s precise voice-over and Christopher Doyle’s fertile, still cinematography depict Vietnam – like Casablanca or Havana – as a luscious haven that openly welcomes you while its tentacles tacitly grab you, the story presents the land and the people as one-dimensional playgrounds for the narcissism of the foreigners. And, through this contradiction we might find the kernel that drives this movie:

Each of these flavorful narratives is nothing less than a façade that carries us toward what seems to be the recurring message in the film: some people are brave, some people are frightened, some people whisper, and some people scream, but the only honest people are dead people. Further, in this film, nobody simply dies. Rather, all the dead are killed. Brutally. In brutal death, their expressions are uniquely (perhaps finally) honest. Such brutal deaths are the expected conclusions when paths of self-delusion clash against each other; when paths of delusion clash, one will win, because living in delusion (with all its requisite nastiness) is still less frightening than facing reality.

Thus, when the film seems to find its resolution and reaches what seems to be its Hollywood ending, we still do not know if anyone was being honest, for no one confesses. We still do not know why the quiet American was killed, for all we are given are still expressions. But we do know that life seems to continue along, one way or another. And if life is an obstacle, then at least the delusions continue.