On Netflix and Amazon Instant.

Considering that we normally think of documentaries as some sort of academic discourse at the fringes of popular cinema, this relatively new genre of Celebrity-driven docs is something peculiar. That we now watch documentaries starring Michael Moore, Morgan Spurlock, and Bill Maher is something inevitable, I suppose. We already have that tradition of following on-screen directors as characters in their features, including Kevin Smith, Spike Lee, and Woody Allen. But, the point here is that we watch some documentaries because of their host celebrities, more than the topic, even though the topics seem to be extensions of those same celebrities.

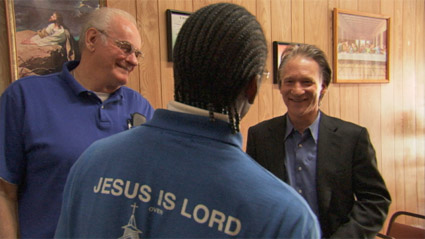

I suspect few people outside of his fan base will watch this movie: in Larry Charles’ documentary “Religulous,” (2008) popular Television talk show host Bill Maher is a playful microphone-toting cynic, roaming the landscapes of Christianity, with a few references to Judaism, Islam, and Scientology. The film is very strong and vastly entertaining in finding absurdities in absurd places, but fizzles when it attempts any serious commentary.

Maher’s central question is simple: how can smart people believe in things that cannot be true? The strength of this question is obvious. The problem, however, is that that question would come from anyone with any belief in anything, and everyone has belief in something. A Democrat wonders how someone could possibly be a Republican. Republican wonders how anyone could be a Democrat. A Christian wonders how a Muslim could possibly not take Jesus as Lord and Savior. A Muslim wonders how someone could possibly believe in the Trinity. Both wonder how an Atheist can possibly embrace a godless existence. An Atheist wonders how the two can possibly believe in an unseen Divinity. But, as Maher shows, it seems that members of respective groups and traditions actually do not wonder about these things, except perhaps as accusations against other groups. Meaning, such questions are asked neither with compassion, nor even concern, nor even curiosity, but with revulsion.

His answer for himself, he shares with his mom: he does not know what he believes or not. At least, that is what he claims, though he praises doubt over faith. So, he is more of a post-Catholic, embracing ideals he associates with Science. In any case, it is from there that he starts on his global journey. The answer for why people believe what they believe permeates the movie: the people who Maher meets believe in religion because it gives them something.

But, what he shows throughout the movie is that most people do not take their beliefs to their logical conclusions, in part because they have not had a need to do so, and in part because they have never been challenged to do so. It is as though they eat from a satisfying meal, not concerning themselves with the recipe or nutritional facts. So, the recurring point in the film is that people follow religion on their own terms, not on his, because what he believes to be gross inconsistencies tend to be for many of the believers, irrelevant. That might be a description of a type of love, in that you attach yourself to the beauties of the beloved, but ignore the uglinesses. On this point, from where he stands, he would have to contend that both points have their validity.

Meaning, on the one hand, he does not believe in such-and-such because it contradicts itself and has holes. On the other hand, taking an atheism to its logical conclusion (because he speaks the language of anti-theist atheism), if there is nothing immaterial to believe in, then it is no problem to believe in supposed fantasies if they give you benefit. So, the non-believer going out of his way to criticize harmless believers is effectively not someone concerned, compassionate, or curious, but a pain in the neck. But, not all of Maher’s criticisms are of harmless believers.

For the first hour or so, when he is attacking Christianity, his structure is interesting. First, he speaks to his family, in his childhood church. Then, he interviews people from opposite ends of a theoretical spectrum: first some anonymous truckers and then a lauded scientist. In both cases, they give unsatisfactory and essentially evasive answers defending belief. Rather, the unspoken real answer is that they believe what they believe simple because they do. But, because of the dominance of science (rather, “scientism,” believing that Science has all the answers) and the dominance of the secular state, the posture of so many believers has been one of inferiority, weakness and defensiveness, often overcompensated later on by fundamentalisms trying to assert an aggressive religiosity. Though it is peripheral to his movie, I should point out that the dominance of Science and the State over religion has less to do with the mythology that science as all the answers and the perceived benefits of secular rule. Rather, we are witnessing the dominance of business (the major sponsor of relevant scientific developments and the primary beneficiary of the market State), and the failure of religion to prove its own utility, except to provide personal comfort and to fuel global tribalism.

From there, he focuses on power and authority. He interviews a former singer who is now a preacher, making the point that the two – stage performers and preachers – are often indistinguishable, require zero credentials, and equally exploit their dedicated followers. Meaning, the movie argues that stage performers and preachers are essentially pimps. Having spent much time with religious preachers across the traditions, I would wholeheartedly agree with this assessment about so many of them, but not nearly all, and maybe not even the majority. But, I have seen and been personally wounded by enough “superstar” preachers that I am skeptical of them more often than I should be.

The strange thing in the film is that everyone keeps resorting to Science. In addressing homosexuality, a preacher asserts that scientists have never found a “gay gene.” Earlier, a believer asserts that scientists concluded some things about the Shroud of Turin, thus allegedly proving the Divinity of Jesus (along with the authenticity of the Shroud). This “scientistic” approach among believers, of making Science the true criterion of acceptability is a problem. We cannot simultaneously believe in miracles and also resort to Science, unless we redefine Science (or we redefine miracles). Otherwise, a miracle is only something that defies Science, and that misses the point.

I have never met a person whose faith rested on belief in miracles ever able to give me satisfactory reasons for belief, though their experiences might be sufficient for their own personal beliefs. I tell my religious students bluntly that if miracles are the foundation of their belief, then their belief is weak. Take for example, the Muslim daily prayer.

Muslims all across the globe, when performing their daily prayers, perform them almost identically. Mainstream Sunni, Shia, and Ibadi (the third major sectarian group, that everyone seems to overlook): the daily prayers are 80-95% identical and that 5-20% variation is probably exaggerated. You witness this at the Hajj; we have all seen the footage in various movies. But, there is no universal manual that teaches Muslims how to pray. Rather, even if someone learns the canonical prayers through book, video, or internet, he or she really learns how to pray from other people in person, who learned from other people in person, who learned from others, theoretically going back 1400 years. The result of this method is that a decentralized body of a billion people pray almost identically. Another example would be the preservation of the content as well as recitation techniques of the Qur’an. Muslims are often rightly criticized for today having some of the lowest literacy rates on the planet (except for a few nations), yet have managed to perpetuate a tradition of mass Qur’anic memorization of the text and its recitation, including memorizing the pauses between each of the words. Both traditions might be written off as the expected products of a rote curriculum, and a simpleton would argue that this emphasis on prayer and memorization is the cause of Muslim secular illiteracy, but I’m speaking about a billion people. That is something beyond a curriculum. Both – the prayer and the Qur’anic memorization – sound quite like miracles to me; but as miracles per se, these should not be the foundation of a Muslim’s faith. So, it follows that very few Muslims even think about these points, because they are taken for granted.

In the movie, a store owner tells a cool story of making a prayer for water, sticking a glass out the window, and watching it suddenly fill up from a sudden rainstorm. But, because they are miracles, they cannot be reproduced, and no attempt is made in the movie to reproduce the miracles. We would think that if he was able to pray up a rainstorm once to find his own faith, he could do it again to help Maher find his faith. I suspect that it is out of politeness that Maher does not ask for the miracle to be reproduced.

Anyways, the criteria for confirming a miracle is often that it is (a) anomalous, and (b) it escapes scientific explanation (theoretically for ever). The skeptic, however, disregards the miracle as coincidence. Unspoken is often (c) timing, in that the perfect event happens at the perfect time. The problem here is that the commonplace – like the currently seven billion examples of unique human consciousness – are not considered miraculous. Again, Muslims rarely consider the prayer or the Qur’anic preservations to be miraculous because they are so commonplace.

Nevertheless, Maher explores the store owner’s beliefs. He asserts that belief in God is akin to belief in Santa Claus, and because the latter is false, so too is the former. That is silly. He focuses on the story of Jonah, may peace be upon him, and the whale, but a stronger target would have been the virgin birth of Jesus which nearly all Christians and Muslims (including myself) believe, may peace be upon him. In the case of a man surviving a few days in the body of a fish, all that is necessary is for it to happen just once in the thousands year long history of humanity; it is harder to argue a virgin birth – even just one – especially when there is no body to point to (and potentially exhume). To be fair, he does criticize the Christian belief in Jesus’ birth, citing its absence in some of the canonical Gospels, as well as citing other examples in history from Egypt and India of Jesus-like figures.

Later, he rightly criticizes the mixture of religion and nationalism. He wonders why and how America became such a vocally Christian country, especially considering that the Founding Fathers are wrongly lionized as believers in Christianity. In the process he digs into a congressman, who, when challenged, stumbles over big words, resorts to silly defenses, and then very quickly retreats. Again, we are shown someone who has not thought through his beliefs, taking them to their logical conclusions, and is quickly stumped. I wish Maher had the same conversations asking the monarchs of Saudi Arabia – claiming to be the custodians of the most sacred sites of Islam – to recite passages of the Qur’an (which I just called a miracle) because many would not be able to. I suspect the same would be true of most of the heads of Muslim majority countries, including those who invoke Islam in their paths to power. Likewise, I wish he would have interviewed some right-wing Israeli leaders about their misuses of Judaism in the pursuit of power; considering how quickly he raced out of a room in fright while interviewing an anti-Zionist rabbi, I’m guessing that this would not happen.

Next, he goes to some sites of religion, including a museum and the Vatican among others.

We visit the Creation Museum in Kentucky. The curator’s “proof” of the authenticity of the Bible is a collection of set pieces that show dinosaurs frolicking with humans, even though the Bible does not make mention of dinosaurs. Maher makes him almost assert that the scientists are part of a global conspiracy of lies. And, this point is serious on multiple levels. First, that such a museum is able to raise so much money that one exhibit costs $27 million. Second, that the method is deception: the museum alleges proof of its foundational scripture by not only showing things that are not in the scripture, but by implicitly asserting that knowledge is dangerous. Third, belief in conspiracies works synonymously with a belief in victimhood; that such a museum exists with such sentiments reveals that the supporters share a perception of victimhood. But, Maher raises a stronger point: why does belief for or against dinosaurs matter for salvation or morality. That question is not answered.

Then he goes to the Vatican. This trip seems unnecessary, except to get him kicked out of a building. But, soon he meets a Senior Vatican Priest, who steals the show. Except for entertaining conversations with a stoic minister of “Cantheism” (some sort of spirituality through marijuana), this priest is the highlight of the entire film. He has wise, feisty answers for all of Maher’s cynical challenges, and seems to win Maher’s approval. Interestingly, when Maher suggest that he is a maverick, the priest denies it. Rather, he is someone who has actually thought through his beliefs (extensively) and sees countless examples of believers losing their way in the name of piety. In my experience, two groups of people within a religious community tend to see their co-religionists “losing their way,” en masse: fundamentalists and scholars.

Fundamentalists, lost in their selective utopian ideals, (often frustratedly) regard their own believing communities as lost. Scholars see a breach between text and practice. But, it is usually the pastoral workers (who are sometimes scholars) who try to provide any reform, reunion, or healing. I wish this interview with this Priest was much longer than the two minutes it seemed to be. But, perhaps it is so short because he has answers to Maher’s comments, for it would contradict Maher’s goals with the film. I’m saying that if we are to clinch Maher’s praise of skepticism, then we would have be skeptical about Maher’s intentions.

He takes issue with this recurring idea in religions that God speaks to specific people, rather than all humanity. He presents this criticism as a refutation, but it is not much of one. First, the obvious point that if we are speaking of God as a supreme being, then naturally God can speak to humanity in any format He chooses. So, if the Supreme Being communicates with creation through select individuals, then that would be His prerogative, because He is the Supreme Being. So, to complain that God speaks in special ways to specific people would be a complaint, but not a refutation. Second, however, many of these religions do not limit communication with and from the Divine through these select individuals, anyway.

He ends the film with an apocalyptic sermon of his own, and naturally, we have to wonder if he considers himself a stage performer, preacher, and pimp. Save for the loud editing, it shares the complete lack of nuance, depth, innovation, and oratory of a boring weekly sermon at a house of worship. Maher asserts that religion must end, that religion is dangerous because it gives power to humans that humans should not have. Essentially, he’s calling for fascism; he uses the same language that fascist movements all use. He opposes faith as anti-rational, opposes certainty as illusion, and praises doubt. Again, his approach is rather selective, disregarding the role of rationality in religion (considering for example that even in Catholicism, the mostly forgotten Bishop Tempier, of Paris, opposed the attention his contemporary St. Thomas Aquinas gave to rationality). It is not that religion is anti-rational; rather, religion is often not as comprehensively rational as he believes it should be. I would agree with him, on this point, except that for me, belief in a radical monotheism is the most rational of the options.

More, importantly, Maher disregards the pacifism of the overwhelming majority of believers and ignores the horrendous violence resulting from wars of secular nationalists. Let’s face facts that much of the world’s violence comes from armies, and much of the world’s civilian violence results from anger, rather than religious zeal. And, the local level, we often see people of religion cleaning up the mess alongside state authorities.

But, despite his hopes, religion will not die, unless it gets replaced by something that is somehow not religion, yet fulfills that seemingly innate need in humanity for religion. Nevertheless, if all religion is fraud, then such cataclysmic destruction will be irrelevant because we will all die one way or another anyways.

Though most of the movie is focused on Christianity, he does speak of Judaism and Islam. His comments on Judaism involve mockery of Moses, may peace be upon him, and a company developing Kosher products for the Sabbath. His comments on Muslims tend to fall into the usual right-wing rhetoric, presenting Muslims as duplicitous anti-Semitic shouting killers hell bent on global domination. I also have to wonder why he had to travel all the way to Europe to interview Muslims; that reinforces the notion that Muslims are a bunch of foreigners. Though each of these depictions of Muslims is seriously problematic and inconsistent, the accusation that Muslims are duplicitous is the most troubling of the troubling list. I have to face this accusation rather frequently, that “Even though you preach mercy and peace, you secretly probably support violence.” Meaning, there is nothing I can say about my beliefs, without risk of being told that I am secretly savage. This accusation against Muslims did not spontaneously appear; it is the result of a conscious campaign. Maher supports it by interviewing a European politician who is outspoken in the movie and in politics in his venom against all things Muslim; and Maher does not challenge him on it, but instead nods in agreement. But, we can point out, that this approach reveals that Maher advertises himself as a liberal, but duplicitously follows right-wing rhetoric.

Still, in both cases Judaism and Islam, Maher also catches his interviewees tripping over themselves with inconsistencies or contradictions. It’s the same problem: he catches people who do not take their views to their logical conclusions. I think this point that he so repeatedly discovers illustrates a deeper problem in our society. We live in such a diverse society, yet hardly know anything about our own faiths and know less about the faiths of others. This phenomenon illustrates that we each really do seem to live in our own bubbles. More than that, this phenomenon illustrates that we are often part of our religious-teams, rather than in some serious transformative quest for the ethereal. In my experience, Atheists tend to be far more literate about religion than majority of their believing counterparts. That is not to say that Atheists are more intelligent; not even close. But, it is far more likely that a former-Catholic-now-Atheist will know a few tidbits about Islam, than a believing Catholic. The same goes for the Muslim equivalent.

Readers know that I’m a poor excuse for a Muslim who teaches in the academy, preaches in the mosque, and spends too much (or not enough) of his quality time watching movies; there is one moment in the film that had me laughing out loud. Maher interviews some miscellaneous elderly Imam at some miscellaneous mosque in Europe, but gets interrupted by some music. The Imam’s cell phone ringtone starts playing “Kashmir” by Led Zeppelin. I’m laughing about that moment as I type this sentence. Hold on. I have to pause to let this laughter out.

Ok, I’m back. Someone outside the circles of Islamic scholars would expect an elderly sage would have a ringtone playing the Qur’an, if he (masculine) were to have a cell phone in the first place. Though that notion is absurd, I can say, with plenty of empirical evidence, that not only do all of the Islamic scholars I know use cell phones, but they tend to be just as silly or colorful as they are serious. A friend, himself an Islamic scholar in his mid-70s, has a ringtone that plays George Thorogood’s “Bad to the Bone.” Another mentioned that he had Usher playing as his ringtone. I would try to explain this very common practice of such Islamic scholars and their ringtone choices, but it’s just human. I will say, though, that there is genre of Islamic literature that poses fun at Muslim preachers, centering itself on a mythical character named Mullah Nasruddin. Further, a text that I teach very frequently, “Rose Garden” (“Gulistan”), by the thirteenth century Persian poet Sa’di, on the surface looks like advice for Kings on ruling their lands. On closer inspection, however, it is a melancholy, irreverent commentary on religious people. It works like The Blues, in the sense that it is sad, but it is still hopeful.

I raise this point for a few reasons. The first is that too many non-religious people, whether they define themselves as agnostic, atheist or anti-theist often fool themselves into thinking that they have the monopoly on critical, as well as humorous, as well as cynical evaluations of religion. The reality is that everyone is part of the conversation and always has been. This includes people of religion. I recently completed a course teaching a text by one of the most revered Muslims of the twentieth century, Muhammad Iqbal (d. 1938), who asserted that just as Physics learned to question its own foundations (in the Einsteinian Era), the task at hand is for religion to do the same.

Thus, compared to some of the giant “secular” thinkers of the past, a few of whom are explored in introductory Sociology and Philosophy courses at any local junior college, the arguments of contemporary popular anti-theists tend to be rather silly. The recurring points in the thought of Dawkins, Hitchens, Harris, and here Bill Maher are simple. First, you have to be stupid to believe in the absurd claims of religion, and (thus) you are enlightened if you part from them. Second, religion is a central cause of the problems of the world. Third, non-religion is a viable alternative. So, is Atheism less stupid than religion? The responses would be equally simple: if these sacred texts in history are frauds, then write something as good and as influential. If religion is a central cause of the problems of the world, then find a method other than fascism and mockery to fix things. Instead, we see the same type of dogmatic fundamentalist-type behavior among anti-theists as we do among believers.

But, these contemporary stars are celebrities, not scholars. In making their points, they cherry pick through their evidences with the precision of a rusty tractor grumbling its way through a forest of big trees. In this movie, Maher positions himself on multiple levels of advantage. First, he has obviously thought about the issues to degrees further than almost everyone he has interviewed, but that is a credit, not a fault. Second, however, he controls the interview, frequently interrupting his victims, and further controlling editing of the final piece. The latter point, however, is true of just about every news magazine anyways, but it fools us into thinking he is being objective.

I realized, long after watching the movie, that I originally disliked it for a few reasons, some of which were unfair. I used to watch Bill Maher, and did enjoy him thoroughly. His appeal – speaking against the hypocrisies and inconsistencies of people of power, religious and secular – was eventually overtaken for me by Jon Stewart. It might just be a personal choice, but Stewart tends to be far more even handed than Maher. When speaking of Islam, Maher today often sounds no different than contemporary right-wingers. In the past, though, especially around 9/11/01, (long before it became popular) Maher was one of the few celebrities who repeatedly featured Muslims on his show, giving us voice.

Additionally, I wanted Maher in this movie to be George Carlin, a freewheeling critic of all authority, but he is not. To be fair, he is a different comedian with a different approach to things. I don’t think that Carlin would have been nearly as successful with television shows the way Maher has been.

Third, I wanted this movie to be something akin to Sacha Baron Cohen‘s interviews as Ali G, Borat, and (the TV version, not the movie version of) Bruno. Even though three of Cohen’s major caricatures – Ali G, Borat, and now The Dictator – are unstated parodied Muslims, I still find him hilarious when he is hilarious. But, Maher is not a caricature. Rather, he presents himself as a quick-thinking regular guy with messy hair and nondescript attire. Still, I do believe the Maher perhaps unintentionally positions the film as something competing with Sacha Baron Cohen, showing the silliness, peculiarities, and at times frightful qualities of everyday people. Maher succeeds here repeatedly, but not reaching the level of genius in some of Cohen’s over-the-top moments. But, to be fair, Cohen’s segments also fail frequently. And, this film is much more intelligent than anything Cohen will probably ever do. The characters he interviews give hints of having interesting backgrounds, like the Satanist who embraces Christianity, but those backgrounds are not pursued, so such characters are left rather flat. The movie even gets interesting when he starts speaking about himself, his childhood, or his struggles with smoking (especially in contrast with his love of drugs), but he remains distant from much intimacy. Still, he is not here to explore people or himself, but to push a negation of religion.

So, reconsidering, the only reason I watched this film (compared to the countless other documentaries critiquing religion) is because it stars Bill Maher, and I do actually like this film, but I wish it gave me more.

Omer Mozaffar teaches cinema and religion at Loyola University, DePaul University, the University of Chicago’s Graham School, and Islamic centers throughout Chicago.