Features

Happiness is being on the road again

By Roger Ebert

November 16, 1986

Most people who are on the road all the time seem to be running from something. Willie Nelson seems to be looking for it. One of his best friends says Willie can’t be happy for long unless he’s going somewhere – by plane, car, train, bus, foot; it doesn’t matter, just as long as he’s in motion. One recent rainy day, Willie flew out of Austin, Texas, and spent some time in Chicago, and later that night laid his head to rest in New York City.

“I guess I’m just restless,” he said here, stirring sugar into his black coffee in the middle of the afternoon. “It’s difficult for me to stay in one spot for long. I really do like to get up and go somewhere, maybe because I’ve done it all my life. Billy Joe Schaffer has a line, about being so restless that moving’s the closest thing to being free.”

Nelson was wearing a trimmed-down version of the bushy beard he grew for “Red-Headed Stranger,” his new movie, and he had his long hair in two braids — he’s letting it grow again, after cutting it short a few years ago. He was in Chicago to promote the movie, a labor of love that he filmed on his Texas ranch with the help of friends, neighbors, and a mysterious Boston woman who turned up one day with a check for $50,000. (The film’s distributor has yet to book a Chicago area theater.)

He is a big star and he doesn’t travel light. There must have been a half dozen business partners, assistants, publicists, movie distributors and old pals who checked into the hotel with him, but it was all so low-key I figured they took their tone from him, and he never seemed in a hurry about anything. I asked him if he still used the bus that was the co-star of “Honeysuckle Rose,” or if he only used private planes now.

“I love the bus,” he said. “You know you’ve been somewhere. Ham and eggs at dawn in some truck stop somewhere, if that’s what you’re hungry for. We live in the bus or in hotels a lot, and we like it. My life is very close to the autobiographical movies, `Honeysuckle Rose’ and `Songwriter.’ “

Those two movies demonstrated Nelson’s strange ability, as a movie actor, to create a powerful character while scarcely seeming to raise his voice. Neither one was a box office hit; indeed, Willie Nelson’s movie career has consisted of sleepers and lost films and projects producers lost interest in.

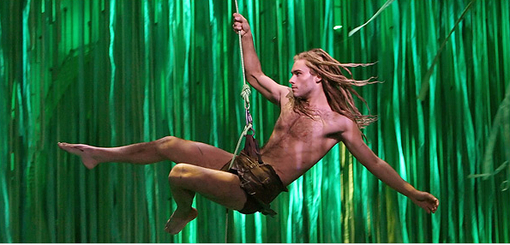

His first starring role was “Honeysuckle Rose,” the 1980 saga of a hard-drinking country music star and the tug-of-war between his wife (Dyan Cannon) and girl friend (Amy Irving). Then came “Barbarosa” (1982), an offbeat Western about two legendary cowboys and their feud with a Mexican land baron. The studio didn’t even want to release that one, even though co-star Gary Busey had recently won an Oscar nomination for “The Buddy Holly Story.” Then in 1984 came “Songwriter,” with Nelson and Kris Kristofferson in the story of a man determined to regain his independence from the pressures of the recording industry. And now here is “Red-Headed Stranger,” inspired by Nelson’s album of 11 years ago which tells the story of a preacher who tries t o tame an evil town, is abandoned by his wife, kills his wife and her lover, and then spends years in exile in the wilderness before riding back in to meet his fate in that same town.

Whatever it is that Nelson has as a movie actor, a lot of important directors have been attracted to it. The first movie was directed by Jerry (“Scarecrow”) Schatzberg, the second by Fred (“Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith”) Schepisi, the third by Alan (“Choose Me”) Rudolph, and this one is the directorial debut of Bill Wittliff, who wrote the first two. In all of them, Nelson plays a recognizable version of himself, as a weathered, quiet, gentle man who gives hints of having suffered more than he should have, and being more cheerful than he has reason to be.

“The movie thing all started after a party one night in Nashville,” Nelson said, remembering. “It was a fund-raiser for some ecological project Robert Redford was sponsoring, and the next day I found myself on the same plane with Redford, flying back to Los Angeles. He asked me if I had ever wanted to be in the movies, and I said, well, yeah, sure, I supposed so. I guess he already had me in mind for something.”

That would have been Redford’s “Electric Horseman” (1979), where Nelson’s official film acting debut was short but unforgettable (he described a woman as being “able to suck the chrome off a trailer hitch”). Even after four starring roles, he said he’s still not happy while he’s making a movie: “It’s difficult for me to sit in one spot for three months.”

And it was difficult to make “Red-Headed Stranger,” he added, because the role was so different from himself. “In the songwriter movies, I was basically just being myself. This one I had to stretch a little. But I wanted to make it. When I wrote the album for some reason I could see a movie being made of it. And I just felt like if it were to be made into a movie, I could probably play that character as well as anybody. I used to sing the song to my kids as a bedtime story.”

It’s kind of a grim story, with the preacher starting out with his high ideals and then murdering what he loved, and descending into self-destruction before he finally gets it together again.

“I think it shows how far down a person can go and then come back, regardless of who he is. And that even a preacher, who is a human being, can drop to that depth and then come back. The thing I wanted to avoid was just turning the movie into one long music video. There was plenty of music available, enough that we could put a song under every scene if we wanted to, but I fought with Wittliff over that. He wanted a lot of music. At first, I didn’t want any music at all. I guess we met in the middle somewhere.”

The result: an odd Western road picture, somewhat strangely cast (Morgan Fairchild plays Nelson’s first wife, and Katharine Ross makes a rare film appearance as the widow who gives him new hope). Nelson spent years trying to finance the project. He described his troubles: “The movie calls for a raging black stallion and a dancing bay pony, and I bought them both when I started the project, but by the time I got the movie made, the dancing bay pony wasn’t dancing too much and the raging black stallion wasn’t raging too much.”

Finally, he said, he and Wittliff pared the budget down to rock bottom and built the sets out back on Nelson’s Texas ranch, and started shooting. One example of cutting corners: In the original script, the bad guys blew up the town’s water tower, but in the finished version, they just open the tap and drain the water – saving the cost of a $40,000 explosion.

“To keep the thing going, we were writing hot checks at one point,” Nelson said. “None of them bounced, though. I guess the people that got them just had enough faith to hold onto them until they figured they were good.”

But you have a lot of money, don’t you? You’re rich and famous.

“Rich, I don’t know about. I don’t have that much money. I make a lot of money and I spend a lot of money. I have a lot of expenses. The music business brings the money in, and the ranches and various real estate that I have take the money out again. My ranch in Texas is not what you’d describe as a money-making proposition. I keep some pleasure horses there and I enjoy the hell out of it, but it’s not a working ranch.”

He poured himself some more coffee and smiled to himself.

“With `Red-Headed Stranger,’ what saved us was the generosity of a woman in Boston named Carolyn Musar. I only mention her name because she hates it whenever I do. She happened to be a fan of mine, and she heard somewhere that we were short of money to finish this movie, and she told her lawyer, “Find out how much those guys need,’ and she was on the set two days later with a $50,000 check as a loan. It came at just the crucial moment.”

Nelson, who said he wasn’t sure when the film would be released, said he was keeping busy. He was featured in a recent “Miami Vice” episode, he went to New York to be honored as “Man of the Year” by the Jewish United Fund, he was planning a tour, and he was still active on the follow-through for Farm-Aid (the fund- and consciousness-raising extravaganza he produced last summer in Champaign-Urbana, Ill.). All of this for a country singer who likes to call himself an outlaw. I asked him what “outlaw” meant to him, now that he was part of the establishment that had once rejected him.

“Freedom,” he said simply. “Freedom to decide for yourself, whatever it is. I think that’s why the term caught on so much with the public; it’s not going the way someone tells you to go.”

It also meant, for a lot of people during Nelson’s earlier days, the wild-and-woolly lifestyle that he celebrated in “Honeysuckle Rose” (which was renamed “On the Road Again” for its TV and video reincarnation). In the movie, as – some said – in real life, Nelson and his sidekicks drank and partied their way from one stop to another, leaving a trail of empty bottles and broken hearts behind. But now the wild life has settled down considerably for many of country music’s outlaws — Nelson’s pals Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson and Waylon Jennings have all gone public with their decisions to stop drinking and/or drugging, and Hank Williams Jr. even wrote a song about how his rowdy old friends had mellowed. I asked Nelson if he would mind a question about his wild reputation.

“I’ll answer any question.”

Well, then, do you still live in the style that made “outlaw” famous?

“I drink less, much less. Moderation is the key. I used to overdo everything.”

Is it hard to make the tours and live the life on the bus when you’re cleaning up your act?

“I think it’s important that you surround yourself with a bunch of guys who have the same head that you do, so you’re all on a somewhat similar level, or when you hit the bandstand it’s not gonna be right. The important thing is that we really do enjoy performing. Other people may call it work. I’m not happy for long unless I’m singing somewhere. Every show is different.”

How do you write a song?

“The way it begins is in my head. A lot of things won’t let you not write them. I don’t actually write anything down for a long time, and so the test is, if I can remember it, it must be worth writing down. If I get out the pencil and paper, I’m already sold on it. But also, I have a belief that any song, if it was good once, it’s still good. That’s why I like to record a lot of other people’s songs, standards, things like the `Stardust’ album (a best seller from 1978).”

Did you get criticism in the country music world for recording “Stardust” and the other pop classics? Did people think that wasn’t pure enough, from a country point of view?

“Not so much criticism as dubiousness. The `Stardust’ album was not thought to be the greatest idea by a lot of people. But these were the songs I’d been playing all my life anyway. And in clubs, people would request `Stardust’ and `Harbor Lights’ and then turn right around and ask for `Fraulein,’ `San Antonio Rose’ or `Whiskey River.’ People just like good music, a lot of different kinds of music. And I was singing `Stardust’ a long time before I was singing country.”

Somehow that doesn’t fit the image.

“Oh, but it’s true. I learned music from my grandparents, and they learned it by mail order from a place called,” Nelson said, pausing, “I think the return envelopes said it was called the Chicago Musical Institution. They’d study under kerosene lamps every night. I watched them, they’d have their lessons out of the mail-order books, and then send them back through the mail, and finally they got their degrees. They were about 60 years old then. Sixty years old and still taking their lessons, still young enough to learn something. They had great spirit. I thought so.

“My granddad died when I was 6. He’d taught me some chords on the guitar. My grandmother played the piano and organ a little, but she was getting old and had arthritis. She taught my sister Bobbie how to play the piano, and I learned from her. I’d play guitar and she’d play piano, and that’s when I first sang ‘Stardust.’ I learned it from her.

“I’ve been singing it since before I knew what it meant.”

Did your grandmother live long enough to see you perform in public?

“Yes, she did. She would come to a place in Fort Worth called the Panther Hall Ballroom whenever I’d play there. She was in her 80s.”

The afternoon was growing dark, and the rain was starting up again. Before long it would be time for Willie Nelson to head out for the airport again, and fly to New York. I asked him how it felt to be “Man of the Year.”

“If they’ve named me that, there must be a few things they don’t know about me,” he said, and chuckled. “I guess I got it because of the Farm Aid thing, which is really one of the things I’ve done in my life that was a great thing. When I first got into the issue of family farms, I had no idea the problem was as severe as it was. I thought we’d do a benefit to call attention to the farmer thing, and Washington would say, `Oh, they’re having a problem,’ and the next day the whole thing would be worked out. But the problem is getting worse. Hundreds of farmers are going under every week.”

Have you ever thought of running for office?

“Yeah. A long time ago. I was approached to run for senator from Texas, and I had to decide, and I decided not to. I’m an entertainer, and so the very fact that in order to become a politician you have to piss off half of the country didn’t seem very smart. Why chop off half of your audience just so you could walk around and say, “I’m a senator’?”

And so that’s how America lost its chance at the first outlaw senator. What about retirement?

“Yeah, I suppose I’ll hang it up someday. Everybody does. But not this year or the next. When I do, I’d like to maybe buy me a little one-pump gas station somewhere in south Texas. You know, pretty far from town, and without much traffic.”

If you’re a Comcast customer, “Red-Headed Stranger” is streaming.

Some 200 of my TwitterPages are linked at the right.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

Manuel de Oliveira is 102: A tribute

The first three scenes from “A Talking Picture” (2003)

The complete film is streaming on Netflix Instant, which introduces it: “A beautiful history professor (Leonor da Silveira) and her 8-year-old daughter embark on a Mediterranean cruise from Lisbon to Bombay. Along the way, they talk about myths, legends and the milestones of Mediterranean civilization. Their compelling discourse about the history of Western civilization eventually includes the ship’s captain, Comandante John Walesa (John Malkovich). Also stars Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas and Stefania Sandrelli.”

Three other films by de Oliveira are streaming on Netflix.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

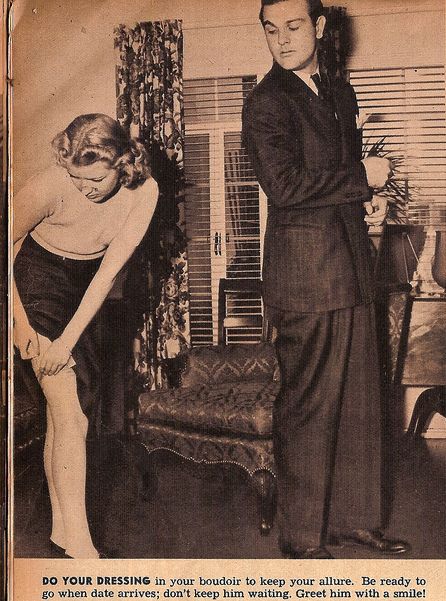

Guys: Danger signals on a date

I had a date like this once. Hell, I was date like this once.

Video Scout: Larry J. Kolb, ex-CIA

The secret of Jacques Tati

26th May 2010

Dear Mr Ebert

Please let me first introduce myself. My name is Richard McDonald the middle grandson of the celebrated French filmmaker Jacques Tatischeff.

Having read with concerned interest your current blog documenting your experiences at this years Cannes Film Festival I hereby obliging write to you on behalf of my grandfathers only direct living family with information that you should be made aware of concerning the often ignored yet historically significant chapter of his life.

As you aware, having seen the trade screening at the Cinema Arcades in Cannes, this year will see the international release of an adaptation of my grandfather’s original l’Illusionniste script by Sylvain Chomet and Pathe Pictures/ Sony Picture Classic. Before participating further in any active promotion of Chomet’s adaptation of Tati’s l’Illusionniste we would appreciate that you first consider how his interpretation greatly undermines both the artistry of my grandfather’s original script whilst shamefully ignoring the deeply troubled personal story that lies at its heart.

I hope that you will be able to appreciate the significance of this information and compassionately understand the hurt that the misrepresentation of history by those involved in this production has already caused.

“Really I assure you, in all my films I did absolutely everything I wanted to do. If you don’t like that, them, I am the only one to blame”

— Jacques Tati: Cahiers du Cinema, 1980

It is well documented that my grandfather, Jacques Tati, wrote the script of l’Illusionniste as a sentimental semi-autobiographical reflection on how he was feeling about himself and in particular what he saw as his personal failings during the 1950’s. It is also documented that the script was written as a personal letter to his teenage daughter. What is less well known however is the depth of his deceitful torment and how in the script he wrestles with the notion of publicly acknowledging his eldest daughter, my mother, who he had under duress from his elder sister heartlessly abandoned during the Second World War. At the time performing at the Lido de Paris with his long term lover, my grandmother Herta Schiel, Tati’s deplorable conduct towards his first child was met with utter disgust by the majority of his then stage colleagues. Thrown out of the Lido by Leon Volterra, it was from this act, having been shunned by the Paris cabaret circuit for his caddish betrayal of one of their own and not as is often wrongly told to avoid Nazi recruiters, that Tati took refugee in the village of Sainte-Sévère in 1943, where he would later shoot Jour de Fete. The stage performers of Paris were a close knit community and in the same way that they had previously provided for Piaf they would also collectively help shelter Tati’s abandoned infant daughter Helga Marie-Jeanne whom as Piaf was born in Paris at the Hôpital Tenon located in the 20th arrondissement.

At its heart the original script for l’Illusionniste focuses on a conjurer who upon finding that his act has became unfashionable is resorted to travel to ever further distant venues to earn a living. It is at one of these locations, originally intended to be a small town in Czechoslovakia that he befriends a young teenage girl who appears to be without family. Enthralled by the illusionist tricks which she believes to be real magic a father/daughter relationship evolves between the movies two protagonists. As the parental relationship builds the conjurer’s engagement in the village comes to an end and the unlikely pair head to the big city, originally set to be Prague. For the first time in her life the young girl is exposed to the enchantment of a big city. Afraid to lose the young girl’s affections to the charms of the city the illusionist unwilling to disappoint her with the truth about his life does everything he can to maintain the notion that his magic is real. However the lure of the city is powerful and the young girl attracts the attention of a handsome young man who exposes the conjurer’s magic as fraudulent, nothing more than cheap tricks, illusions created to entertain an audience. Unable to hold onto her affections once his charade has been exposed the script concludes with the conjurer disappearing off into the sunset free of his deceit having as he always known he would lost the affections of the young girl to youth and the vibrancy of the city once she was able to see beyond his theatrics.

How the original script for l’Illusionniste reflects my grandfather’s personal troubled dilemmas at its time of writing can be explained by taking account of the following facts.

1 It is well documented that Tati, my grandfather, wrote l’Illusionniste an emotive semi-autobiographical account of how during the 1950’s he felt about himself and in particular what he saw as his professional and personal failings at the time.

2 It has been acknowledged that the script for l’Illusionniste was written as a personal letter to Tati’s teenage daughter. Sophie his second child was not a teenager at the time of its writing, only his eldest daughter, Helga Marie-Jeanne whom he had adversely neglected as an infant was. In 1955 Helga was thirteen years of age, Sophie had just turned nine. Consecutive versions of l’Illusionniste script exist dated from 1955 through to 1959.

3 Tati played with idea’s for l’Illusionniste throughout the mid to late 1950’s the writing of which coincided with a letter written to him by his eldest daughter, Helga Marie-Jeanne. As a refugee Helga Marie-Jeanne had become trapped in Marrakech during the Moroccan 1955 uprising for independence against its French protectorate. Having been at the centre of the Christmas Eve bombing of the main Marrakech market in which she witnessed the massacre of a number of her boarding school friends, Helga Marie-Jeanne was actively encouraged by the French Consulate to flee Morocco for her own safety. Holding only a French passport she wrote to her father in hope that he would show compassion towards her plight and help her escape the hostilities that had built up in Morocco by offering her safe passage back to her home city of Paris. He was never forthcoming with help. However the request for help from his own daughter could only have weighed heavily on Tati the man, the artist, who had during the same period written the most sensitive observations of childhood innocence and parenthood with Academy Award winning Mon Oncle.

In Mon Oncle Tati would take the opportunity to swipe fun at the notion of arranged marriages which his elder sister Nataile had manipulated him into after the rejection of his own daughter in real life. Natalie had an overbearing influence over Tati and his abandonment of his eldest daughter was greatly influenced by her depraved intervention. Tati’s script for l’Illusionniste parallels many of the dilemmas he was facing in his real life at the time, acceptance that he wasn’t getting any younger, the failing popularity of live cabaret, befriending and taking on his parental duties towards a teenage girl he knew little about, bringing that teenager to a big city and the dilemma of ultimately losing the child’s affection once the veil of his stage persona was exposed.

4 Tati, in keeping with his preference of not working with professional actors, had singled out Sylvette David who had modelled for Picasso for the role as the teenage girl due to her resemblance to Bridget Bardot. In her letter from Morocco Helga Marie-Jeanne had innocently joked that the locals of Marrakech had nicknamed her the brunette Bardot of the Sahara. David did not sit for Picasso until 1954 so it can only be concluded that Tati did not know of her until after this date.

5 Tati had set l’Illusionniste in the Czech capital city of Prague. The mother of his eldest child Herta Schiel was of duel nationality and escaped the German annexation of Vienna using Czech papers. She remained a Czech citizen throughout the war. Tati always referred to Herta as being Czech.

6 The original l’Illusionniste script focuses on how from a distance the teenage girl believes with utter wonderment the enchanting life the conjurer inhabits. After making a sentimental bond through his stage persona with the girl he does not have the heart to reveal to the teenager that his magic and what she sees as his very life are little more than a fabricated illusion. Throughout his career Tati was often quoted as saying that his Hulot was just a character he had created and he himself was a very different person to what was seen on screen. His eldest daughter’s perception of him as a child was mainly formed from what she had seen of him in character on screen. l’Illusionniste script deals directly with the dilemma he was facing on how would his daughter respond once she realised the gentile man on the silver screen was not the same man he was after the dim theatre lights had been switched back on.

7 The original script for l’Illusionniste concludes with the magician walking off into the sunset wiser for the experience and free of his deceit. Tati had hoped that by openly apologising to his eldest daughter he would in some way be free of his real life deception that increasingly contradicted his growing public persona. The very title, l’Illusionniste illustrates how Tati was aware at how his public persona was a veil that contradicted the real man. Conjurers by their very craft are deceitful.

8 Tati had never intended to play the role of the illusionist himself instead he had intended to cast Pierre Etaix in the leading role but Etaix fell out with Tati over moral issues concerning the script. A bitter feud surfaced and the two men never again spoke. Tati copyrighted l’Illusionniste script at the beginning of the 1960’s as he was concerned that both Etaix and Jean-Claude Carrière would try and steal it. All of Tati’s old music hall colleagues knew of his eldest daughter he had fathered in Paris during the Second World War and the majority felt his actions to one of their own betrayed them all. It is highly likely Etaix or Carrière would have known about Tati’s eldest child.

9 My Grandmother Herta Schiel never lost contact with her Parisian music hall colleagues and throughout her life would travel nearly every year back to Paris. It was through these connections that she learnt that Tati had written a script for the daughter he had shamefully betrayed. No name was ever given to the script but knowing of only two other un-produced scripts by Tati, The Occupation of Berlin (which has currently conveniently gone missing) and Confusion it can be concluded that l’Illusionniste with the parallels it draws is indeed that script. The l’Illusionniste was written around the same period as The Occupation of Berlin when Tati must have been reflecting upon his war years. Performers of the Lido de Paris, Bal Tabarin and A.B.C. who had known Tati both as a friend and colleague since he himself was a teenager still remarkably live in Paris and to this day are in regular contact with his eldest daughter Helga Marie-Jeanne. Nothing that Tati did in his movies was by accident but exist as a result of meticulous planning to precisely convey his very personal vision.

On hearing that Sylvain Chomet had started production on l’Illusionniste in what for centuries has been my father’s family home county of Northumberland on the Scottish border I confidentially approached him with the difficult true story that lay at the heart of my grandfather’s script. Gratefully acknowledging l’Illusionniste true meaning that he had apparently always known was written by Tati as a “personal letter to his daughter” Chomet invited me to his Edinburgh studio to read the script he had adapted and to see the progress he was making.

After a long conversation Chomet revealed he had obtained the script for l’Illusionniste from my Aunt Sophie Tatischeff following nothing more than a single telephone conversation he had with her whilst seeking permission to use a segment of Jour de Fete in his Belleville Rendez-Vous animated movie. Sophie died regrettably young in October 2001 a full two years before Belleville was released in late 2003 and it is questionable that she would have released what she had protected for so long to an unknown director she would never in person meet and who at the time had nothing to his name but a well received short animation. It was impossible for Sophie to give Chomet the script for l’Illusionniste after she had seen Belleville Rendez-Vous as he has often been quoted as saying.

Chomet justifies using an animated caricature of Tati by saying that Sophie never wanted anyone to play her father however she would have been well aware that her father never intended playing the part of the Illusionist himself, he had no conjuring skills and wanted solely to concentrate his efforts on writing and directing this most personal movie. As stated above the role was originally written for Pierre Etaix.

After Chomet became aware of the troubled story that lay beneath l’Illusionniste he informed the current caretakers of my grandfather’s estate, Jerome Deschamps and Mikall Micheff at Les Films de Mon Oncle, who without consent published the most deplorable inaccurate account of my family in the biography Jacques Tati by Jean-Philippe Guerand. This intolerable disfiguring of our lives provoked us as a family and all that remains of the Tatischeff line with no choice but to finally put on record our true heritage to which everybody who is currently promoting themselves through my grandfathers celebrity have no legitimate claim whatsoever.

The partners at Les Films de Mon Oncle certainly never had a hand in the creation of my grandfathers oeuvre nor are they in anyway related to him. When Tati became bankrupt the Deschamps family chose to do nothing but glee at his downfall. It is quite deplorable that today they should be allowed to parasitically exploit both his abilities and failings whilst disturbingly distorting history. Deschamps came into ownership of four of Tati’s movies after he purchased them from a terminally ill Sophie Tatischeff in the last year of her life to pay her debts (she’d lost a fortune with her recording studio, Son our Son) as she did not want to die with the shame of bankruptcy like her father. Deschamps absolutely did not inherit the Tatischeff estate as a rightful heir as he would like the world to think. Working closely with highly respected Princeton academic David Bellos who is credited with writing the most discerning biographical account of my grandfather’s life we have been able to publicly document for the first time the true events that were Tati’s War years..

What we ask is that you please try and understand the most unjust personal anguish that my family has faced for so long with nothing but the utmost reserved dignity and why the promoting of my grandfathers most personal script on the issue without acknowledging his troubled intentions for its creation, never mind how it has been spitefully reinterpreted, will only add further insult to everyone personally involved. Not recognising the source for l’Illusionniste shows not only disrespect for Tati the artist but also subverts the man’s only redeeming response towards his daughter he inconsiderately abandoned.

To the outside world my grandfather, Jacques Tati was the great mime, the celebrated cinematic artist who held the most special gift of being able to entertain and make people laugh through his unique humane way of portraying the often crazy world in which we all live. However as he always maintained his celluloid characters were not him but creations born from his real life observations. Like many artists he was also troubled for this was also the same man who in complete contradiction to his professional screen persona had heartlessly abandoned both his eldest child, Helga Marie-Jeanne and her mother, Herta Schiel in the most shameful of circumstances. Tati courted and performed on stage at the Lido de Paris with Herta for the two years previous to the birth of their child. Inseparable Tati would enthusiastically discuss with Herta his ambitious plans to create his own movies and as early as 1941 he already had L’Ecole des Facteurs/Jour de Fete envisaged.

In Herta existed a vibrant brave young woman who at just seventeen years of age had the foresight alongside her sister Molly to flee the impending annexation of Vienna whilst courageously providing shielding and eventual safe passage to Morocco for their most admired childhood Jewish friend, Heinz Lustig. A young woman barely out of childhood herself who having arrived in Pairs with little more than a visa allowing her only to perform on the stage went on to courageously at great personal risk learn Morse Code and translate intercepted German messages from the front line into French for the Resistance movement before they were sent to De Gaulle in London. A woman whose only mistake was to fall in love then be betrayed by the gangling clown who would go on to charm the world with laughter in the way he ridiculed and questioned it.

In a single year, 1943 Herta’s gallantry would be severely challenged as she found herself isolated in a foreign occupied city holding a needy new born child having lost both the man she loved and heartbreakingly her sister to tuberculosis. The mother of Tati’s first child was a valiant woman who was not afraid to stand up for the freedom of Europe and today rightfully deserves not to be forgotten.

Tati’s eldest daughter, Helga Marie-Jeanne always maintaining a Parisian soul would spend most of her life to adulthood in between Paris, Marrakech and Vienna. Having grown without knowing the love of a father in adulthood she could not bare the thought of bringing the shame she had suffered as a child for his betrayal to her half-brother, Pierre and sister, Sophie. It is for this reason alone that at the height of her father’s celebrity she remained dignifiedly silently even under pressure to create scandal. Helga Marie-Jeanne had suffered enough as a child for her father’s betrayal, in adulthood she determinedly decided to make her own way in the world. In honour of Helga Marie-Jeanne’s dignified humility and her mother’s wartime intelligence work Croix de Guerre awarded Parisian Resistance leader Dr Jacques Weil would stand in the place of her father when she married in England in the summer of 1965. Today as a much loved retired grandmother living in the northeast of England the least she deserves is respectful acknowledgement. Had she not remained resolutely silent it is highly unlikely that her father, Jacques Tatischeff would have been able to complete his cinematic oeuvre that still enthralls today.

My grandfather’s artistry did not come without a price and the one who suffered the most for his compulsive behaviour was inexcusably his eldest daughter. Had it not been for the love of her brave astute mother, the goodwill of others and Helga Marie-Jeanne’s own self discipline her fate would have been far bleaker.

My family’s story is unfortunately not the romantic fiction of Truffaut’s Last Metro or Curtiz’s Casablanca. It is however a true account of how during that most horrendous period in modern history people’s moral character was challenged when faced with adversity. Had Tati not survived his military service defending the French borders on the Western Front he might well have died a war hero. Instead the subsequent war years would see him conjure up the most indefensible family tragedy, a betrayal that runs in complete opposition to the legendary tale of how his own grandmother had rescued her son from Russia. The suffering of a child is inexcusable in any society. The sabotaging of Tati’s original l’Illusionniste script without recognizing his troubled intentions so that it resembles little more than a grotesque eclectic nostalgic homage to its author is the most disrespectful act that shows nothing but a total lack of compassion towards both the artist and the child it was meant to address.

Before his death Tati called for his body to be thrown out with the garbage as through his own eyes his life had been a failure. He bemoaned to friends his misgivings and how through his own errors of judgment he would never experience the joy of being a grandparent. We have opened this painful chapter of our lives not out of any vengeance but so that we can now be allowed to lay to rest a previous generation’s mistakes, there is no spite only sorrow for what is ultimately a family tragedy. To fully appreciate an artist’s work you first must acknowledge the person and the life they had lived.

If the integrity of my grandfather’s work means anything to you then please take into account the wishes of his only three grandchildren who united stand loyally by their adored mother, the daughter he had heartlessly abandoned as a child and later addressed l’Illusionniste to. Together we ask that you please show moral compassion and chose in the future not to participate in the misrepresentation of our family history to suit the parasitic benefit of others. That Sylvain Chomet, Pathe Pictures, Sony Picture Classics and Les Films de Mon Oncle dare to rub my grandfather’s remorse on our doorstep without respectfully acknowledging the facts is intolerable. The truth deserves a voice so that at the very least we do not forget the sacrifices made by others for our liberty.

“On le pleure mort,il aurait fallu l’aider vivant”

–Paris Match 19th November 1982 Obituary of Jacques Tati.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

Amazon.com Widgets

Yours sincerely

Richard Tatischeff Schiel McDonald

e. e. cummings lives in a pretty how heaven

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

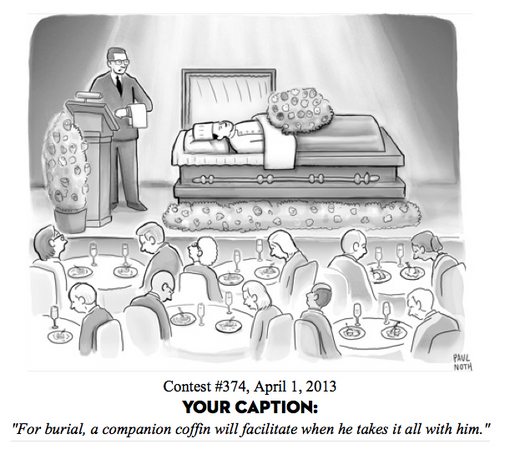

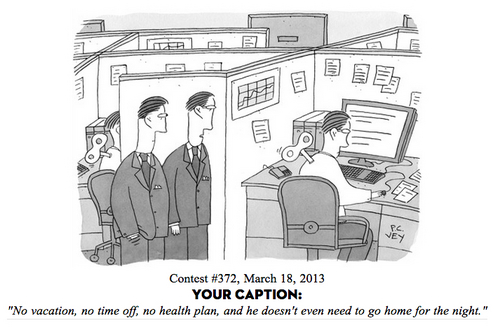

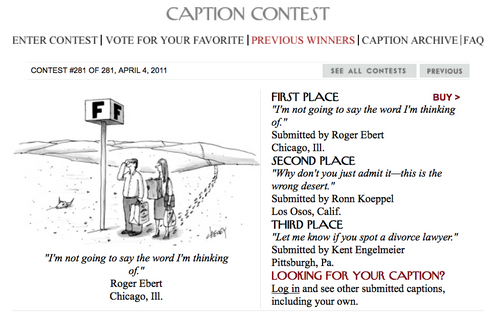

Yes! I won the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest!

Click to enlarge.Enter here for this week’s contest.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

“The Premature Burial,” by Edgar Allan Poe

THERE are certain themes of which the interest is all-absorbing, but which are too entirely horrible for the purposes of legitimate fiction. These the mere romanticist must eschew, if he do not wish to offend or to disgust. They are with propriety handled only when the severity and majesty of Truth sanctify and sustain them. We thrill, for example, with the most intense of “pleasurable pain” over the accounts of the Passage of the Beresina, of the Earthquake at Lisbon, of the Plague at London, of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, or of the stifling of the hundred and twenty-three prisoners in the Black Hole at Calcutta. But in these accounts it is the fact-it is the reality-it is the history which excites. As inventions, we should regard them with simple abhorrence.

I have mentioned some few of the more prominent and august calamities on record; but in these it is the extent, not less than the character of the calamity, which so vividly impresses the fancy. I need not remind the reader that, from the long and weird catalogue of human miseries, I might have selected many individual instances more replete with essential suffering than any of these vast generalities of disaster. The true wretchedness, indeed-the ultimate woe-is particular, not diffuse. That the ghastly extremes of agony are endured by man the unit, and never by man the mass-for this let us thank a merciful God!

To be buried while alive is, beyond question, the most terrific of these extremes which has ever fAllan to the lot of mere mortality. That it has frequently, very frequently, so fAllan will scarcely be denied by those who think. The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins? We know that there are diseases in which occur total cessations of all the apparent functions of vitality, and yet in which these cessations are merely suspensions, properly so called. They are only temporary pauses in the incomprehensible mechanism. A certain period elapses, and some unseen mysterious principle again sets in motion the magic pinions and the wizard wheels. The silver cord was not for ever loosed, nor the golden bowl irreparably broken. But where, meantime, was the soul?

Apart, however, from the inevitable conclusion, a priori that such causes must produce such effects-that the well-known occurrence of such cases of suspended animation must naturally give rise, now and then, to premature interments-apart from this consideration, we have the direct testimony of medical and ordinary experience to prove that a vast number of such interments have actually taken place. I might refer at once, if necessary to a hundred well authenticated instances. One of very remarkable character, and of which the circumstances may be fresh in the memory of some of my readers, occurred, not very long ago, in the neighboring city of Baltimore, where it occasioned a painful, intense, and widely-extended excitement. The wife of one of the most respectable citizens-a lawyer of eminence and a member of Congress-was seized with a sudden and unaccountable illness, which completely baffled the skill of her physicians. After much suffering she died, or was supposed to die. No one suspected, indeed, or had reason to suspect, that she was not actually dead. She presented all the ordinary appearances of death. The face assumed the usual pinched and sunken outline. The lips were of the usual marble pallor. The eyes were lustreless. There was no warmth. Pulsation had ceased. For three days the body was preserved unburied, during which it had acquired a stony rigidity. The funeral, in short, was hastened, on account of the rapid advance of what was supposed to be decomposition.

The lady was deposited in her family vault, which, for three subsequent years, was undisturbed. At the expiration of this term it was opened for the reception of a sarcophagus;-but, alas! how fearful a shock awaited the husband, who, personally, threw open the door! As its portals swung outwardly back, some white-apparelled object fell rattling within his arms. It was the skeleton of his wife in her yet unmoulded shroud.

A careful investigation rendered it evident that she had revived within two days after her entombment; that her struggles within the coffin had caused it to fall from a ledge, or shelf to the floor, where it was so broken as to permit her escape. A lamp which had been accidentally left, full of oil, within the tomb, was found empty; it might have been exhausted, however, by evaporation. On the uttermost of the steps which led down into the dread chamber was a large fragment of the coffin, with which, it seemed, that she had endeavored to arrest attention by striking the iron door. While thus occupied, she probably swooned, or possibly died, through sheer terror; and, in failing, her shroud became entangled in some iron- work which projected interiorly. Thus she remained, and thus she rotted, erect.

In the year 1810, a case of living inhumation happened in France, attended with circumstances which go far to warrant the assertion that truth is, indeed, stranger than fiction. The heroine of the story was a Mademoiselle Victorine Lafourcade, a young girl of illustrious family, of wealth, and of great personal beauty. Among her numerous suitors was Julien Bossuet, a poor litterateur, or journalist of Paris. His talents and general amiability had recommended him to the notice of the heiress, by whom he seems to have been truly beloved; but her pride of birth decided her, finally, to reject him, and to wed a Monsieur Renelle, a banker and a diplomatist of some eminence. After marriage, however, this gentleman neglected, and, perhaps, even more positively ill-treated her. Having passed with him some wretched years, she died,-at least her condition so closely resembled death as to deceive every one who saw her. She was buried-not in a vault, but in an ordinary grave in the village of her nativity. Filled with despair, and still inflamed by the memory of a profound attachment, the lover journeys from the capital to the remote province in which the village lies, with the romantic purpose of disinterring the corpse, and possessing himself of its luxuriant tresses. He reaches the grave. At midnight he unearths the coffin, opens it, and is in the act of detaching the hair, when he is arrested by the unclosing of the beloved eyes. In fact, the lady had been buried alive. Vitality had not altogether departed, and she was aroused by the caresses of her lover from the lethargy which had been mistaken for death. He bore her frantically to his lodgings in the village. He employed certain powerful restoratives suggested by no little medical learning. In fine, she revived. She recognized her preserver. She remained with him until, by slow degrees, she fully recovered her original health. Her woman’s heart was not adamant, and this last lesson of love sufficed to soften it. She bestowed it upon Bossuet. She returned no more to her husband, but, concealing from him her resurrection, fled with her lover to America. Twenty years afterward, the two returned to France, in the persuasion that time had so greatly altered the lady’s appearance that her friends would be unable to recognize her. They were mistaken, however, for, at the first meeting, Monsieur Renelle did actually recognize and make claim to his wife. This claim she resisted, and a judicial tribunal sustained her in her resistance, deciding that the peculiar circumstances, with the long lapse of years, had extinguished, not only equitably, but legally, the authority of the husband.

The “Chirurgical Journal” of Leipsic-a periodical of high authority and merit, which some American bookseller would do well to translate and republish, records in a late number a very distressing event of the character in question.

An officer of artillery, a man of gigantic stature and of robust health, being thrown from an unmanageable horse, received a very severe contusion upon the head, which rendered him insensible at once; the skull was slightly fractured, but no immediate danger was apprehended. Trepanning was accomplished successfully. He was bled, and many other of the ordinary means of relief were adopted. Gradually, however, he fell into a more and more hopeless state of stupor, and, finally, it was thought that he died.

The weather was warm, and he was buried with indecent haste in one of the public cemeteries. His funeral took place on Thursday. On the Sunday following, the grounds of the cemetery were, as usual, much thronged with visiters, and about noon an intense excitement was created by the declaration of a peasant that, while sitting upon the grave of the officer, he had distinctly felt a commotion of the earth, as if occasioned by some one struggling beneath. At first little attention was paid to the man’s asseveration; but his evident terror, and the dogged obstinacy with which he persisted in his story, had at length their natural effect upon the crowd. Spades were hurriedly procured, and the grave, which was shamefully shallow, was in a few minutes so far thrown open that the head of its occupant appeared. He was then seemingly dead; but he sat nearly erect within his coffin, the lid of which, in his furious struggles, he had partially uplifted.

He was forthwith conveyed to the nearest hospital, and there pronounced to be still living, although in an asphytic condition. After some hours he revived, recognized individuals of his acquaintance, and, in broken sentences spoke of his agonies in the grave.

From what he related, it was clear that he must have been conscious of life for more than an hour, while inhumed, before lapsing into insensibility. The grave was carelessly and loosely filled with an exceedingly porous soil; and thus some air was necessarily admitted. He heard the footsteps of the crowd overhead, and endeavored to make himself heard in turn. It was the tumult within the grounds of the cemetery, he said, which appeared to awaken him from a deep sleep, but no sooner was he awake than he became fully aware of the awful horrors of his position.

This patient, it is recorded, was doing well and seemed to be in a fair way of ultimate recovery, but fell a victim to the quackeries of medical experiment. The galvanic battery was applied, and he suddenly expired in one of those ecstatic paroxysms which, occasionally, it superinduces.

The mention of the galvanic battery, nevertheless, recalls to my memory a well known and very extraordinary case in point, where its action proved the means of restoring to animation a young attorney of London, who had been interred for two days. This occurred in

1831, and created, at the time, a very profound sensation wherever it was made the subject of converse.

The patient, Mr. Edward Stapleton, had died, apparently of typhus fever, accompanied with some anomalous symptoms which had excited the curiosity of his medical attendants. Upon his seeming decease, his friends were requested to sanction a post-mortem examination, but declined to permit it. As often happens, when such refusals are made, the practitioners resolved to disinter the body and dissect it at leisure, in private. Arrangements were easily effected with some of the numerous corps of body-snatchers, with which London abounds; and, upon the third night after the funeral, the supposed corpse was unearthed from a grave eight feet deep, and deposited in the opening chamber of one of the private hospitals.

An incision of some extent had been actually made in the abdomen, when the fresh and undecayed appearance of the subject suggested an application of the battery. One experiment succeeded another, and the customary effects supervened, with nothing to characterize them in any respect, except, upon one or two occasions, a more than ordinary degree of life-likeness in the convulsive action.

It grew late. The day was about to dawn; and it was thought expedient, at length, to proceed at once to the dissection. A student, however, was especially desirous of testing a theory of his own, and insisted upon applying the battery to one of the pectoral muscles. A rough gash was made, and a wire hastily brought in contact, when the patient, with a hurried but quite unconvulsive movement, arose from the table, stepped into the middle of the floor, gazed about him uneasily for a few seconds, and then-spoke. What he said was unintelligible, but words were uttered; the syllabification was distinct. Having spoken, he fell heavily to the floor.

For some moments all were paralyzed with awe-but the urgency of the case soon restored them their presence of mind. It was seen that Mr. Stapleton was alive, although in a swoon. Upon exhibition of ether he revived and was rapidly restored to health, and to the society of his friends-from whom, however, all knowledge of his resuscitation was withheld, until a relapse was no longer to be apprehended. Their wonder-their rapturous astonishment-may be conceived.

The most thrilling peculiarity of this incident, nevertheless, is involved in what Mr. S. himself asserts. He declares that at no period was he altogether insensible-that, dully and confusedly, he was aware of everything which happened to him, from the moment in which he was pronounced dead by his physicians, to that in which he fell swooning to the floor of the hospital. “I am alive,” were the uncomprehended words which, upon recognizing the locality of the dissecting-room, he had endeavored, in his extremity, to utter.

It were an easy matter to multiply such histories as these-but I forbear-for, indeed, we have no need of such to establish the fact that premature interments occur. When we reflect how very rarely, from the nature of the case, we have it in our power to detect them, we must admit that they may frequently occur without our cognizance. Scarcely, in truth, is a graveyard ever encroached upon, for any purpose, to any great extent, that skeletons are not found in postures which suggest the most fearful of suspicions.

Fearful indeed the suspicion-but more fearful the doom! It may be asserted, without hesitation, that no event is so terribly well adapted to inspire the supremeness of bodily and of mental distress, as is burial before death. The unendurable oppression of the lungs- the stifling fumes from the damp earth-the clinging to the death garments-the rigid embrace of the narrow house-the blackness of the absolute Night-the silence like a sea that overwhelms-the unseen but palpable presence of the Conqueror Worm-these things, with the thoughts of the air and grass above, with memory of dear friends who would fly to save us if but informed of our fate, and with consciousness that of this fate they can never be informed-that our hopeless portion is that of the really dead-these considerations, I say, carry into the heart, which still palpitates, a degree of appalling and intolerable horror from which the most daring imagination must recoil. We know of nothing so agonizing upon Earth- we can dream of nothing half so hideous in the realms of the nethermost Hell. And thus all narratives upon this topic have an interest profound; an interest, nevertheless, which, through the sacred awe of the topic itself, very properly and very peculiarly depends upon our conviction of the truth of the matter narrated. What I have now to tell is of my own actual knowledge-of my own positive and personal experience.

For several years I had been subject to attacks of the singular disorder which physicians have agreed to term catalepsy, in default of a more definitive title. Although both the immediate and the predisposing causes, and even the actual diagnosis, of this disease are still mysterious, its obvious and apparent character is sufficiently well understood. Its variations seem to be chiefly of degree. Sometimes the patient lies, for a day only, or even for a shorter period, in a species of exaggerated lethargy. He is senseless and externally motionless; but the pulsation of the heart is still faintly perceptible; some traces of warmth remain; a slight color lingers within the centre of the cheek; and, upon application of a mirror to the lips, we can detect a torpid, unequal, and vacillating action of the lungs. Then again the duration of the trance is for weeks-even for months; while the closest scrutiny, and the most rigorous medical tests, fail to establish any material distinction between the state of the sufferer and what we conceive of absolute death. Very usually he is saved from premature interment solely by the knowledge of his friends that he has been previously subject to catalepsy, by the consequent suspicion excited, and, above all, by the non-appearance of decay. The advances of the malady are, luckily, gradual. The first manifestations, although marked, are unequivocal. The fits grow successively more and more distinctive, and endure each for a longer term than the preceding. In this lies the principal security from inhumation. The unfortunate whose first attack should be of the extreme character which is occasionally seen, would almost inevitably be consigned alive to the tomb.

My own case differed in no important particular from those mentioned in medical books. Sometimes, without any apparent cause, I sank, little by little, into a condition of hemi-syncope, or half swoon; and, in this condition, without pain, without ability to stir, or, strictly speaking, to think, but with a dull lethargic consciousness of life and of the presence of those who surrounded my bed, I remained, until the crisis of the disease restored me, suddenly, to perfect sensation. At other times I was quickly and impetuously smitten. I grew sick, and numb, and chilly, and dizzy, and so fell prostrate at once. Then, for weeks, all was void, and black, and silent, and Nothing became the universe. Total annihilation could be no more. From these latter attacks I awoke, however, with a gradation slow in proportion to the suddenness of the seizure. Just as the day dawns to the friendless and houseless beggar who roams the streets throughout the long desolate winter night-just so tardily- just so wearily-just so cheerily came back the light of the Soul to me.

Apart from the tendency to trance, however, my general health appeared to be good; nor could I perceive that it was at all affected by the one prevalent malady-unless, indeed, an idiosyncrasy in my ordinary sleep may be looked upon as superinduced. Upon awaking from slumber, I could never gain, at once, thorough possession of my senses, and always remained, for many minutes, in much bewilderment and perplexity;-the mental faculties in general, but the memory in especial, being in a condition of absolute abeyance.

In all that I endured there was no physical suffering but of moral distress an infinitude. My fancy grew charnel, I talked “of worms, of tombs, and epitaphs.” I was lost in reveries of death, and the idea of premature burial held continual possession of my brain. The ghastly Danger to which I was subjected haunted me day and night. In the former, the torture of meditation was excessive-in the latter, supreme. When the grim Darkness overspread the Earth, then, with every horror of thought, I shook-shook as the quivering plumes upon the hearse. When Nature could endure wakefulness no longer, it was with a struggle that I consented to sleep-for I shuddered to reflect that, upon awaking, I might find myself the tenant of a grave. And when, finally, I sank into slumber, it was only to rush at once into a world of phantasms, above which, with vast, sable, overshadowing wing, hovered, predominant, the one sepulchral Idea.

From the innumerable images of gloom which thus oppressed me in dreams, I select for record but a solitary vision. Methought I was immersed in a cataleptic trance of more than usual duration and profundity. Suddenly there came an icy hand upon my forehead, and an impatient, gibbering voice whispered the word “Arise!” within my ear.

I sat erect. The darkness was total. I could not see the figure of him who had aroused me. I could call to mind neither the period at which I had fAllan into the trance, nor the locality in which I then lay. While I remained motionless, and busied in endeavors to collect my thought, the cold hand grasped me fiercely by the wrist, shaking it petulantly, while the gibbering voice said again:

“Arise! did I not bid thee arise?”

“And who,” I demanded, “art thou?”

“I have no name in the regions which I inhabit,” replied the voice, mournfully; “I was mortal, but am fiend. I was merciless, but am pitiful. Thou dost feel that I shudder.-My teeth chatter as I speak, yet it is not with the chilliness of the night-of the night without end. But this hideousness is insufferable. How canst thou tranquilly sleep? I cannot rest for the cry of these great agonies. These sights are more than I can bear. Get thee up! Come with me into the outer Night, and let me unfold to thee the graves. Is not this a spectacle of woe?-Behold!”

I looked; and the unseen figure, which still grasped me by the wrist, had caused to be thrown open the graves of all mankind, and from each issued the faint phosphoric radiance of decay, so that I could see into the innermost recesses, and there view the shrouded bodies in their sad and solemn slumbers with the worm. But alas! the real sleepers were fewer, by many millions, than those who slumbered not at all; and there was a feeble struggling; and there was a general sad unrest; and from out the depths of the countless pits there came a melancholy rustling from the garments of the buried. And of those who seemed tranquilly to repose, I saw that a vast number had changed, in a greater or less degree, the rigid and uneasy position in which they had originally been entombed. And the voice again said to me as I gazed:

“Is it not-oh! is it not a pitiful sight?”-but, before I could find words to reply, the figure had ceased to grasp my wrist, the phosphoric lights expired, and the graves were closed with a sudden violence, while from out them arose a tumult of despairing cries, saying again: “Is it not-O, God, is it not a very pitiful sight?”

Phantasies such as these, presenting themselves at night, extended their terrific influence far into my waking hours. My nerves became thoroughly unstrung, and I fell a prey to perpetual horror. I hesitated to ride, or to walk, or to indulge in any exercise that would carry me from home. In fact, I no longer dared trust myself out of the immediate presence of those who were aware of my proneness to catalepsy, lest, falling into one of my usual fits, I should be buried before my real condition could be ascertained. I doubted the care, the fidelity of my dearest friends. I dreaded that, in some trance of more than customary duration, they might be prevailed upon to regard me as irrecoverable. I even went so far as to fear that, as I occasioned much trouble, they might be glad to consider any very protracted attack as sufficient excuse for getting rid of me altogether. It was in vain they endeavored to reassure me by the most solemn promises. I exacted the most sacred oaths, that under no circumstances they would bury me until decomposition had so materially advanced as to render farther preservation impossible. And, even then, my mortal terrors would listen to no reason-would accept no consolation. I entered into a series of elaborate precautions. Among other things, I had the family vault so remodelled as to admit of being readily opened from within. The slightest pressure upon a long lever that extended far into the tomb would cause the iron portal to fly back. There were arrangements also for the free admission of air and light, and convenient receptacles for food and water, within immediate reach of the coffin intended for my reception. This coffin was warmly and softly padded, and was provided with a lid, fashioned upon the principle of the vault-door, with the addition of springs so contrived that the feeblest movement of the body would be sufficient to set it at liberty. Besides all this, there was suspended from the roof of the tomb, a large bell, the rope of which, it was designed, should extend through a hole in the coffin, and so be fastened to one of the hands of the corpse. But, alas? what avails the vigilance against the Destiny of man? Not even these well-contrived securities sufficed to save from the uttermost agonies of living inhumation, a wretch to these agonies foredoomed!

There arrived an epoch-as often before there had arrived-in which I found myself emerging from total unconsciousness into the first feeble and indefinite sense of existence. Slowly-with a tortoise gradation-approached the faint gray dawn of the psychal day. A torpid uneasiness. An apathetic endurance of dull pain. No care- no hope-no effort. Then, after a long interval, a ringing in the ears; then, after a lapse still longer, a prickling or tingling sensation in the extremities; then a seemingly eternal period of pleasurable quiescence, during which the awakening feelings are struggling into thought; then a brief re-sinking into non-entity; then a sudden recovery. At length the slight quivering of an eyelid, and immediately thereupon, an electric shock of a terror, deadly and indefinite, which sends the blood in torrents from the temples to the heart. And now the first positive effort to think. And now the first endeavor to remember. And now a partial and evanescent success. And now the memory has so far regained its dominion, that, in some measure, I am cognizant of my state. I feel that I am not awaking from ordinary sleep. I recollect that I have been subject to catalepsy. And now, at last, as if by the rush of an ocean, my shuddering spirit is overwhelmed by the one grim Danger-by the one spectral and ever-prevalent idea.

For some minutes after this fancy possessed me, I remained without motion. And why? I could not summon courage to move. I dared not make the effort which was to satisfy me of my fate-and yet there was something at my heart which whispered me it was sure. Despair- such as no other species of wretchedness ever calls into being- despair alone urged me, after long irresolution, to uplift the heavy lids of my eyes. I uplifted them. It was dark-all dark. I knew that the fit was over. I knew that the crisis of my disorder had long passed. I knew that I had now fully recovered the use of my visual faculties-and yet it was dark-all dark-the intense and utter raylessness of the Night that endureth for evermore.

I endeavored to shriek-, and my lips and my parched tongue moved convulsively together in the attempt-but no voice issued from the cavernous lungs, which oppressed as if by the weight of some incumbent mountain, gasped and palpitated, with the heart, at every elaborate and struggling inspiration.

The movement of the jaws, in this effort to cry aloud, showed me that they were bound up, as is usual with the dead. I felt, too, that I lay upon some hard substance, and by something similar my sides were, also, closely compressed. So far, I had not ventured to stir any of my limbs-but now I violently threw up my arms, which had been lying at length, with the wrists crossed. They struck a solid wooden substance, which extended above my person at an elevation of not more than six inches from my face. I could no longer doubt that I reposed within a coffin at last.

And now, amid all my infinite miseries, came sweetly the cherub Hope-for I thought of my precautions. I writhed, and made spasmodic exertions to force open the lid: it would not move. I felt my wrists for the bell-rope: it was not to be found. And now the Comforter fled for ever, and a still sterner Despair reigned triumphant; for I could not help perceiving the absence of the paddings which I had so carefully prepared-and then, too, there came suddenly to my nostrils the strong peculiar odor of moist earth. The conclusion was irresistible. I was not within the vault. I had fAllan into a trance while absent from home-while among strangers-when, or how, I could not remember-and it was they who had buried me as a dog-nailed up in some common coffin-and thrust deep, deep, and for ever, into some ordinary and nameless grave.

As this awful conviction forced itself, thus, into the innermost chambers of my soul, I once again struggled to cry aloud. And in this second endeavor I succeeded. A long, wild, and continuous shriek, or yell of agony, resounded through the realms of the subterranean Night.

“Hillo! hillo, there!” said a gruff voice, in reply.

“What the devil’s the matter now!” said a second.

“Get out o’ that!” said a third.

“What do you mean by yowling in that ere kind of style, like a cattymount?” said a fourth; and hereupon I was seized and shaken without ceremony, for several minutes, by a junto of very rough-looking individuals. They did not arouse me from my slumber-for I was wide awake when I screamed-but they restored me to the full possession of my memory.

This adventure occurred near Richmond, in Virginia. Accompanied by a friend, I had proceeded, upon a gunning expedition, some miles down the banks of the James River. Night approached, and we were overtaken by a storm. The cabin of a small sloop lying at anchor in the stream, and laden with garden mould, afforded us the only available shelter. We made the best of it, and passed the night on board. I slept in one of the only two berths in the vessel-and the berths of a sloop of sixty or twenty tons need scarcely be described. That which I occupied had no bedding of any kind. Its extreme width was eighteen inches. The distance of its bottom from the deck overhead was precisely the same. I found it a matter of exceeding difficulty to squeeze myself in. Nevertheless, I slept soundly, and the whole of my vision-for it was no dream, and no nightmare-arose naturally from the circumstances of my position-from my ordinary bias of thought-and from the difficulty, to which I have alluded, of collecting my senses, and especially of regaining my memory, for a long time after awaking from slumber. The men who shook me were the crew of the sloop, and some laborers engaged to unload it. From the load itself came the earthly smell. The bandage about the jaws was a silk handkerchief in which I had bound up my head, in default of my customary nightcap.

The tortures endured, however, were indubitably quite equal for the time, to those of actual sepulture. They were fearfully-they were inconceivably hideous; but out of Evil proceeded Good; for their very excess wrought in my spirit an inevitable revulsion. My soul acquired tone-acquired temper. I went abroad. I took vigorous exercise. I breathed the free air of Heaven. I thought upon other subjects than Death. I discarded my medical books. “Buchan” I burned. I read no “Night Thoughts”-no fustian about churchyards-no bugaboo tales-such as this. In short, I became a new man, and lived a man’s life. From that memorable night, I dismissed forever my charnel apprehensions, and with them vanished the cataleptic disorder, of which, perhaps, they had been less the consequence than the cause.

There are moments when, even to the sober eye of Reason, the world of our sad Humanity may assume the semblance of a Hell-but the imagination of man is no Carathis, to explore with impunity its every cavern. Alas! the grim legion of sepulchral terrors cannot be regarded as altogether fanciful-but, like the Demons in whose company Afrasiab made his voyage down the Oxus, they must sleep, or they will devour us-they must be suffered to slumber, or we perish.

THE END

¶

Illustration at top by Antoine Wiertz (1806-1865), a Belgian painter. “Tales from the Crypt” from Golden Age Comic Book Stories. All other illustrations from the superb Edgar Allen Poe illustration contest.

The evolution of the Batmobile

The source of this extraordinary graphic can be found at the bottom.

Amazon.com Widgets

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

Aaargh! I’m turning into a monster!

This film is by Krishna Shenoi, one of the Far-Flung Correspondents on my site. He is now 17, having started with these demos some years ago. Krishna is surely one of the most gifted young filmmakers and writers on the internet,

Two years ago:

Here is Krishna Shenoi’s YouTube channel.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

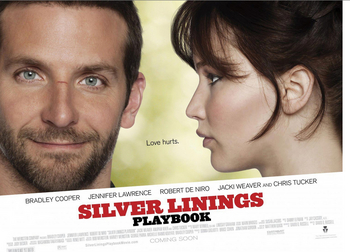

My revised predictions at about 1:40 pm CST 2/24/2013

After giving my Official Outguess Ebert guesses in announcing my annual Oscar winners contest, a few weeks later–with my ear to the ground–I made some revisions: “Silver Linings Playbook” for Best Picture and Emmanuelle Riva for “Best Actress,” in “Amour.”

My official Outguesses must remain unchanged. My revised predictions don’t count. Fair’s fair.

An apology. Some readers found it impossible to enter, because of problems with the link. It took them to a registration form for the Sun-Times web site, and you must be registered to enter.

This, and only this, is the correct page for my Guesses. It links to our registration page. They expected to see a ballot.

Here’s a link to my review of “Amour.” I gave it four stars, and listed it as one of the year’s ten Best. Holding an Outguess contest about it may strike some as a trifle silly. Unless you win the Delta Vacaions trip for two for Marvel’s “Iron Man 3.”

And here is my review of The Weinstein Company’s “Silver Linings Playbook.”

A Labor Day concert

☑ Photo of Pete Seeger’s banjo by Roger Ebert; taken at the Weavers reunion at the Toronto Film Festival in 2004. All of my TwitterPages are linked under the category Pages in the right margin of this page.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

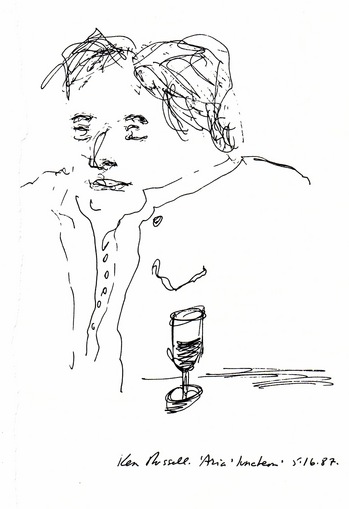

“London Moods,” a 1961 short by Ken Russell

Top drawing by Roger Ebert

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

Amazon.com Widgets

The movie alphabet, blah blah blah, if you’ll excuse me

thetoaster2006 knows the movies.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

Time travel movies in a surreal universe

This animation is explained in this New Scientist article. I remain incapable of encompassing additional dimensions, and wonder if in fact they exist only in math. I’m assured they exist, and are necessary. If they did not exist, I would not exist. I Exist, Therefore They Am.

This is where it gets me: The film visualizes Earth seen from Above in this brave new universe. IS there an Above? Where (and When) are we viewing it from?

Early prototype of Twitter Vine

If this is a waste of your time, what will their damn fool new App be?

Twitter theoretical research:

Early field trial:

Now here is a demonstration of the planned length of the Twitter Vine:

Joey Lauren Adams on Joey Lauren Adams

Does her smile light up a room, or what?

Joey Lauren Adams Remembers Joey Lauren Adams Movies from Joey Lauren Adams