Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira made a film in the early 1980s that he requested not be shown to the public before his death. That turned out to be more than three decades after the film was shot: Oliveira died in April at 106, following the most prolific period of his career; his recent films include “The Strange Case of Angelica” and “Gebo and the Shadow.” Titled “Visit, or Memories and Confessions,” this unearthed film, slightly more than an hour long, screened at Cannes Classics last night—on celluloid, no less.

Funded in 1981 (the festival catalog gives the completion date as 1982), “Visit” is—it should come as a surprise to no one—an intensely personal movie, essentially a family album in motion. “It’s a film by me, about me,” Oliveira says in voiceover as the movie begins. “Right or wrong, it’s done.” Cued by an alternating man-and-woman narration, the movie is largely set on the grounds of a house that Oliveira tell us he has lived in since 1942. Part of the occasion for making the movie, it seems, is that he has had to sell the home to pay some debts.

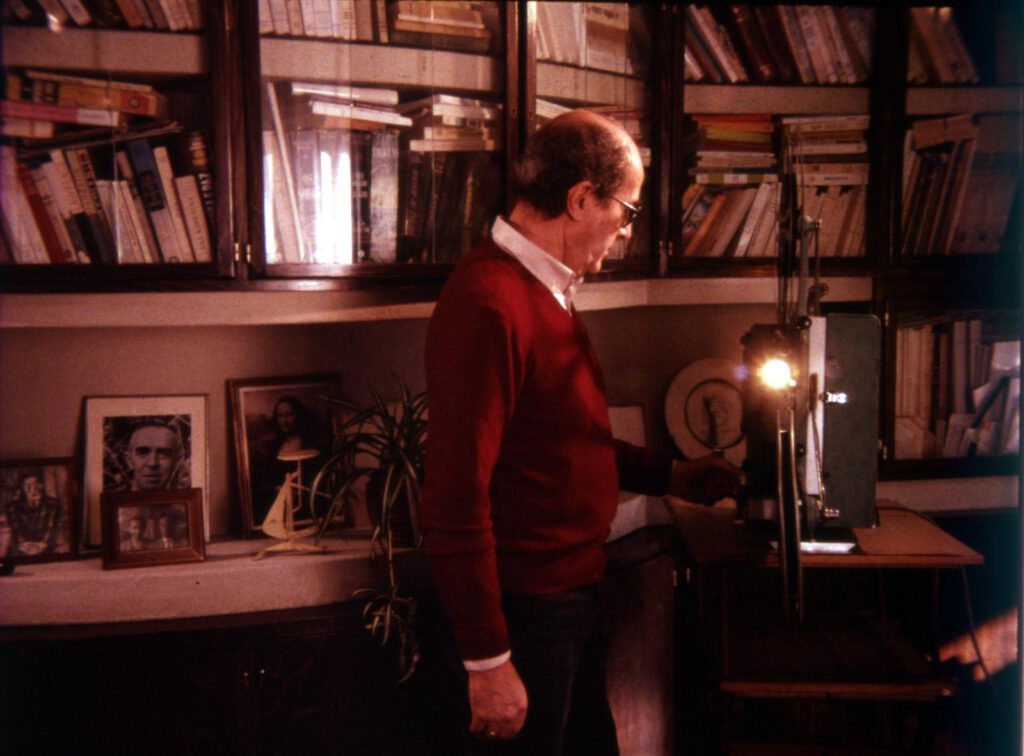

At the risk of reading too much into Oliveira’s intentions, you can see why he might have wanted the movie released as a sort of ghost story. Much of “Visit” concerns the haunting emptiness of this once-bustling home: We hear constant footsteps and watch doors open, Jean Cocteau–style, as we move from room to room, but a good portion of the film goes by before we actually see a human being. The first is Oliveira himself, who appears at the typewriter where he writes his treatments and turns to the camera to address us.

His musings are as idiosyncratic as they are private. He waxes philosophical, shows us photographs and film footage of his family, and recalls visits to the house by such figures as the great film theorist André Bazin. His wife turns up briefly (“You can’t separate the artist from the man,” she says), but this is primarily Oliveira’s reflection on his own life. Late in the film, in a powerful anecdote, he speaks of his 1963 arrest by the secret police under Portugal’s then-repressive government. “I’ve always sacrificed everything so I could make my films,” he says. “Visit” closes with a flourish suggesting that this director who lived more than a century remained eternally young.