You can’t be a Superman fan without being a little bit defensive.

Superman’s a great symbol because of the unique way he, as an alien with a battery of superpowers, relates to puny mortals. He has godlike abilities but chooses to champion “Truth, justice, and the American way.” He is genuinely a self-made man: a smalltown Kansan who, after discovering his extra-terrestrial origins, decides to defend the values taught by his adoptive human parents. If that isn’t goofy enough, Superman also fights extra-dimensional imps whenever he’s not changing outfits in phone booths or hanging out in his glacial Fortress of Solitude. He’s a child’s dream in an adult body that will remain iconic as long as we believe that might can still make right.

Superman is, as media critic and short story writer Harlan Ellison once joked, one of four characters that everyone knows (the other three are Dracula, Mickey Mouse, and Sherlock Holmes). But the character is widely dismissed as a square, especially when compared to DC Comics’ other main draw, the brooding Batman. Today, Batman comics consistently outsell Superman books. Batman is thought of as tragic and recognizably human, while Superman is aloof and invulnerable. Common wisdom holds that Batman’s mix of flamboyance and psychological realism makes it easier to identify with the billionaire Bruce Wayne than with Superman’s alter ego Clark Kent, a sweet bumbler toiling in a dying industry; likewise, Batman’s physical vulnerability and flawed, self-justifying morality are supposedly easier to relate to than Superman’s bulletproof detachment and Boy Scout code.

For proof, see the Quentin Tarantino-penned speech about Superman’s identity in Kill Bill, Vol. 2. David Carradine’s title character theorizes that Clark Kent is a disingenuous mask Superman puts on to “critique” the human race. If that’s not dispiriting enough for you, play Injustice: Gods Among Us, a new fighting video game in which heroes and villains beat the snot out of each other after Superman goes crazy and murders Lois Lane while she’s pregnant with their son. If you’re still not convinced, read recent comics that riff on the cynical assumption that if Superman were real, he would be evil. These include Irredeemable, in which a Superman-type hero loses it and begins killing his teammates, and The Mighty, about a government-sanctioned Superman stand-in with sinister ulterior motives.

As a comics property, Superman has been rejuvenated by everyone from editor Mort Weisinger in the late ’50s to writer/artist John Byrne in the mid-’80s. But regardless of the period, Superman always seems to need to be revamped, revived, and recycled. He is, to use comics critic Tom Crippen’s keen phrase, the mainstream comics’ industry’s “hood ornament.” In a 2007 Comics Journal essay about a collection of ’50s Superman comics, Crippen wrote:

“Today, it’s impossible to imagine Superman being cancelled. Next, they’d cancel corn flakes, and Ivory soap. Let’s say they did somehow beam him out of existence. Does anyone doubt that superhero comics could chug along unchanged with their mutants, and super-group team-ups, and Batman graphic novels? Superman is really the appendix of the superhero genre, a super-appendix that’s as big as a spine and completely inoperable. He will always be with us: his genre’s template, a headache for writers, a childish hood ornament atop a faux-serious industry. He tells us where we’re coming from and that perhaps we’ve traveled less far than we’d like to think.”

“Today, it’s impossible to imagine Superman being cancelled. Next, they’d cancel corn flakes, and Ivory soap. Let’s say they did somehow beam him out of existence. Does anyone doubt that superhero comics could chug along unchanged with their mutants, and super-group team-ups, and Batman graphic novels? Superman is really the appendix of the superhero genre, a super-appendix that’s as big as a spine and completely inoperable. He will always be with us: his genre’s template, a headache for writers, a childish hood ornament atop a faux-serious industry. He tells us where we’re coming from and that perhaps we’ve traveled less far than we’d like to think.”

Crippen’s provocative but fair piece suggests that many creators have overthought the character in an attempt to modernize him (more on this later). But there’s the rub: how to update a character while staying true to his essential identity and not alienating fans?

Unfortunately, creators that have enough vision to make new and worthwhile superhero stories are rare. Too many artists, in TV, comics, or film, are content to be, to paraphrase artist Gil Kane in a 1996 Comics Journal interview, exceptional “handball players” — people who are good but not great at practicing a narrow skill set that’s of interest to few. The same is true of people telling superhero stories.

A lot of these tales are tied up in establishing narrative continuity between crossover events and revised origin stories. Few are striking enough on their own terms to impact the totality of the character, much less pop culture itself. In making this list of the best Superman stories, I wanted to single out some great handball players, but write about their achievements in a way that wouldn’t seem like connoisseurship for its own sake. That this is admittedly a highly subjective list doesn’t mean such notable creators as J.M. Dematteis, Dan Jurgens, Greg Rucka, James Robinson, Louise Simonson, and others should be ignored. I’ve tried to be as inclusive as possible while being open about my preferences. Nevertheless, the list’s core theme is simple: these are the stories that best balance the mythic, realistic, and ridiculous aspects of Superman’s still-developing story.

In The Kents, writer John Ostrander and artist Timothy Truman tell a different kind of origin story in this John Ford-inspired period western set during the American Civil War. Densely over-written, with extensive info-dump dialogue and epistolary asides, The Kents begins in the present. Clark Kent’s adoptive father Jonathan finds a trove of letters written by his ancestors. The letters follow the Kents’ pre-Superman ancestors in Kansas, which in the early 1900s was not yet an independent state. The stories give readers a sense of where the Kents’ ethics comes from. Abolitionist Silas Kent and and his two sons Jebediah and Nathaniel have moved to Kansas hoping to protect freed slaves’ rights. But while Nathaniel, Silas’s elder son, believes in his father’s cause, Jebediah isn’t convinced a white man should stick his neck out for disenfranchised freedmen. The Kents follows Jebediah and Nathaniel’s feud as it plays out on battlefields and homesteads.

Ostrander’s symbolism is sometimes too heavy-handed, as when he re-imagines Superman’s red “S” as a red snake embroidered in a pentagram on an Iroquois healing blanket. But The Kents is just as often remarkable for its simultaneously cartoonish and thoughtful characterizations. Ostrander thankfully never reduces his heroes to simple martyrs. Even Silas is humble enough to want to influence popular opinion by writing op-ed columns instead of running for US Senate. Similarly, the book’s villains aren’t just black-hat-wearing thugs. While lynch mob leader Luther Reid is depicted as a race-baiting hick, he’s no more inhuman than John Brown, the real-life abolitionist priest that lead several bloody attacks on pro-slavery Kansans. Truman’s art, neatly inked by Tom Mandrake, is some of his best, alternating Neal Adams-esque photorealism with Robert Crumb-like caricatures. And the scene in which Nathaniel shakily forges a relationship with a family of freed slaves is wonderful for the unsentimental, clear-eyed way he explains himself. Jebediah tells the freedmen that he doesn’t want to be the dreamy idealist Jebediah thinks he is. Instead, he wants to be an activist who fights for a personal rather than an abstract belief. Getting to know this family is what spurs Jebediah on in his righteous cause.

Ostrander’s symbolism is sometimes too heavy-handed, as when he re-imagines Superman’s red “S” as a red snake embroidered in a pentagram on an Iroquois healing blanket. But The Kents is just as often remarkable for its simultaneously cartoonish and thoughtful characterizations. Ostrander thankfully never reduces his heroes to simple martyrs. Even Silas is humble enough to want to influence popular opinion by writing op-ed columns instead of running for US Senate. Similarly, the book’s villains aren’t just black-hat-wearing thugs. While lynch mob leader Luther Reid is depicted as a race-baiting hick, he’s no more inhuman than John Brown, the real-life abolitionist priest that lead several bloody attacks on pro-slavery Kansans. Truman’s art, neatly inked by Tom Mandrake, is some of his best, alternating Neal Adams-esque photorealism with Robert Crumb-like caricatures. And the scene in which Nathaniel shakily forges a relationship with a family of freed slaves is wonderful for the unsentimental, clear-eyed way he explains himself. Jebediah tells the freedmen that he doesn’t want to be the dreamy idealist Jebediah thinks he is. Instead, he wants to be an activist who fights for a personal rather than an abstract belief. Getting to know this family is what spurs Jebediah on in his righteous cause.

The Kents may have been originally conceived as a separate, non-Superman-related subject, but this scene really gets at why the best Superman stories identify Superman as a human first and an alien second. Babylon 5 creator turned comics writer J. Michael Straczynski reached a similar conclusion in “Grounded,” a recent Superman story in which the character wanders around America on foot in an attempt re-affirm his humble roots. Also be sure to check out Mark Millar, Dave Johnson, and Killian Plunkett’s Red Son and J.M. Dematteis and Eduardo Barretto’s Speeding Bullets, two stories that speculate that growing up in Kansas had a huge effect on Superman’s upbringing.

9) Superboy in Tales of the Legion of Superheroes, as edited by Mort Weisinger (1958-1970)

The only DC property reworked more than Superman is The Legion of Superheroes, a team of teenaged superheroes from the 31st century. In 1958, Superman editor Mort Weisinger needed a way to boost Superman’s flagging popularity, so writer Otto Binder and artist Al Plastino created the Legion, a group whose members’ powers dwarfed even Superman’s. In their earliest incarnation, the Legion palled around with Superman, then Superboy. In these stories, Superman is idolized by the Legion, but they befriend him before he’s had the chance to develop into a legendary figure. Superboy and the Legion learn how to be superheroes together, which appealed to the Legion’s first prepubescent readers. When Superman escaped to the Legion’s future, he found friends who had similar responsibilities but none of his guilt or anxiety. He fit in because he wasn’t a role model, but rather the quintessential adolescent, goofing off and fighting evil aliens alongside Wiesinger characters Triplicate Girl, Bouncing Boy, and Matter Eater Lad.

The early Legion adventures are sweet, lighthearted, and crammed with the kind of absurd creativity that typified DC’s Silver Age (1956-1970). Every panel has a new plot development, and it’s explained in breathless expository captions and word balloons. It’s no wonder then that Superman apologist/historian/critic Tom Crippen considers Weisinger’s tenure as the editor of DC’s Superman titles to be the character’s apex. In 2007, Crippen wrote in The Comics Journal: “For almost half a century superhero comics have traveled in a spiral, bobbling out from a zero-point of childish wish-fulfillment and heading in the general direction of adult realism, or pseudo-adult semi-realism. The zero-point, the dead start of the process, is where you will find Superman in his prime. It’s 1958 and he’s demonstrating that, no matter what else can be said about superheroes, they make perfect sense as a small child’s dream.”

The early Legion adventures are sweet, lighthearted, and crammed with the kind of absurd creativity that typified DC’s Silver Age (1956-1970). Every panel has a new plot development, and it’s explained in breathless expository captions and word balloons. It’s no wonder then that Superman apologist/historian/critic Tom Crippen considers Weisinger’s tenure as the editor of DC’s Superman titles to be the character’s apex. In 2007, Crippen wrote in The Comics Journal: “For almost half a century superhero comics have traveled in a spiral, bobbling out from a zero-point of childish wish-fulfillment and heading in the general direction of adult realism, or pseudo-adult semi-realism. The zero-point, the dead start of the process, is where you will find Superman in his prime. It’s 1958 and he’s demonstrating that, no matter what else can be said about superheroes, they make perfect sense as a small child’s dream.”

Weisinger was ironically something of a control freak, so the sense of play that established Crippen’s “zero-point” wasn’t ideal for artists like Curt Swan, whose singular contributions to the character are praised further up on this list. But while he was Superman’s editor, Weisinger, along with writers like Otto Binder and Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel, originated many popular Silver Age characters, including the tiny Kryptonian inhabitants of the bottle-sized city of Kandor, and Superman’s cousin Supergirl. One of Weisinger’s most memorable characters is Mon-El, a Legionnaire with Superman-like powers that must stay in the Phantom Zone, the extra-dimensional prison Superman uses to contain super-strong villains, or else he’ll die of lead poisoning. Superman’s legacy with the Legion of Superheroes was recently celebrated by writer Geoff Johns in such titles as “Superman and the Legion of Super-Heroes,” and “Last Son,” the latter of which features Mon-El in a prominent supporting role.

8) “Camelot Falls,” by Kurt Busiek, Carlos Pacheco, Fabian Nicieza, Renato Guedes, and David Antoine Williams (2006-2007)

“Camelot Falls“ is that rare contemporary Superman story that unostentatiously nails the character without reinventing the wheel, and centers on a thoughtful character-defining question: would Superman ever back down from a fight if he knew that he could only win by surrendering? In “Camelot Falls,” Superman is confronted with visions of an unsettling future. Humanity will die, annihilated by an unstoppable villain, and it’s all his fault. The Atlantean wizard Arion, an obscure fan-favorite, shows Superman what will happen if he doesn’t abandon Earth, and never look back. He’s warned that this is a fight he can’t win. So he’s met with an impossible choice: leave Earth, or indirectly kill everyone he loves.

“Camelot Falls” is refreshing because while it is essentially a story that justifies Superman’s existence, its creators never shy away from the character’s cornier aspects. Writer Kurt Busiek takes his sweet time setting up his version of the Man of Steel’s world. For example, he’ll teasingly introduce supporting characters, including a killer Russian monster and a newly revived Prankster, then wait a long time to reveal why they’re significant. This is a story that spends a good chunk of time in Atlantis and features a bad guy named Khyber, a creature named Subjekt 13, and a flock of irresponsible fledgling Gods passing through Metropolis like migrating super-geese. But once the A-plot kicks off in “Camelot Falls,” the story picks up steam.

“Camelot Falls” is refreshing because while it is essentially a story that justifies Superman’s existence, its creators never shy away from the character’s cornier aspects. Writer Kurt Busiek takes his sweet time setting up his version of the Man of Steel’s world. For example, he’ll teasingly introduce supporting characters, including a killer Russian monster and a newly revived Prankster, then wait a long time to reveal why they’re significant. This is a story that spends a good chunk of time in Atlantis and features a bad guy named Khyber, a creature named Subjekt 13, and a flock of irresponsible fledgling Gods passing through Metropolis like migrating super-geese. But once the A-plot kicks off in “Camelot Falls,” the story picks up steam.

Busiek characteristically wears his encyclopedic knowledge of Super-history lightly, and does a fine job balancing Clark Kent’s melodramatic conversations with building-toppling set pieces. It’s particularly exciting to see the Prankster, a theretofore dated character, reimagined so effectively. In “Camelot Falls,” the Prankster is a mercernary second-stringer that gets paid top dollar to distract Superman while other villains make their getaway cross-town. Busiek juggles a lot of disparate plot points in this 13-issue story, and he does it so well that one can’t help but marvel at the consistency with which he pulls together his sprawling narrative. And Carlos Pacheco’s clean, detailed pencils are equally well-suited for body language-centric conversations and crater-making slug-fests. “Camelot Falls” is easily one of the best recent Superman stories.

7) Superman: Secret Identity, by Kurt Busiek and Stuart Immonen (2004)

Busiek’s other great recent Superman story concerns a world in which Superman initially exists as a concept. In this world, Clark Kent knows Superman as a comic book character. His schoolmates tease him mercilessly because his parents’ thought it would be funny to name him, a Kansas-born Kent, Clark. But after a metorite crash-lands in his backyard, Clark develops his namesake’s abilities. And as Clark grows up, he accepts both his responsibilities and limitations, from adolescence to old age. Secret Identity is, as its title implies, a story about Clark Kent, and how Superman’s great powers (never fully explained in the story) don’t mean anything if the power wielding them isn’t mature enough to use them responsibly.

In that sense, Secret Identity confirms Tom Crippen’s speculation about Superman’s nature as, “the human-scale figure in our mental diagram of reality.” In a 2010 Comics Journal essay, Crippen wrote: “No matter what he stands next to, that thing also becomes human scale: not just the dinosaurs but also icebergs, moons, galaxies, giant robots–the universe. We need him, but we know he’s a lie; if the universe actually were our size, our universe wouldn’t need obviously non-human qualities (flight, planet-juggling ability). There wouldn’t be any need for superhuman–just human. There wouldn’t be any need for super.”

In that sense, Secret Identity confirms Tom Crippen’s speculation about Superman’s nature as, “the human-scale figure in our mental diagram of reality.” In a 2010 Comics Journal essay, Crippen wrote: “No matter what he stands next to, that thing also becomes human scale: not just the dinosaurs but also icebergs, moons, galaxies, giant robots–the universe. We need him, but we know he’s a lie; if the universe actually were our size, our universe wouldn’t need obviously non-human qualities (flight, planet-juggling ability). There wouldn’t be any need for superhuman–just human. There wouldn’t be any need for super.”

Indeed, Busiek’s Clark is super because his humanity is constantly placed in the story’s foreground. Secret Identity‘s main narration consists of excerpts from Clark’s confessional autobiography. It’s filled with rationalizations, and reflections on the people in his life, and the reasons he did the things he did. This device lets Busiek prioritize observational detail over general philosophizing about who Superman really is and what he stands for. In one particularly incisive exchange, a dumpy news editor tells Clark, then a cub reporter, that his prose is stunning, but that it’s written from the perspective of an alienated outsider. The editor jokingly suggests that Clark get laid more often, maybe see the world. The point is made: Clark must grow into a role he originally thought of as just a pulpy myth. By the time that his twin daughters are grown and the torch has passed from one generation of super-men to the next, Clark has grown in ways that most Superman stories only hint at. It’s a subtle and accomplished character study.

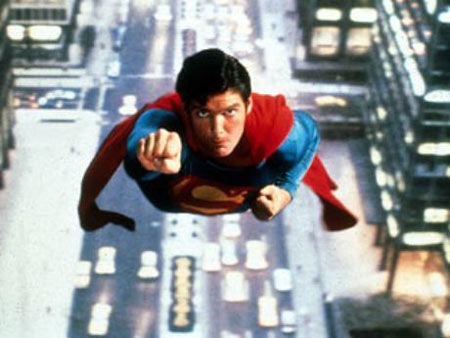

6) Superman: The Movie (1978)

Superman: The Movie is understandably revered as one of the most impressive takes on the character and his world. The film has so many fantastic elements, including Christopher Reeve’s aw-shucks modesty and understated humility, John Williams’s triumphal score, and Margot Kidder’s endearing take-no-guff attitude. But one of the most exciting things about the film is its fundamental understanding of Superman’s symbolic importance. In just one line of dialogue, the film succinctly tells us why Superman is a red, yellow, and blue peacock: he wants people to see him, and to follow him in doing everything they can to help those in need. In one scene, a young Clark protests to Glen Ford’s Jonathan “Pa” Kent that he should be able to run as fast and as far as he can: “It isn’t showing off if someone’s doing what they’re capable of doing.” That line is essential. It explains why Clark feels so helpless when Pa dies, and he can only think to wail, “All those powers, and I couldn’t even save him.” This is the Ben/Peter Parker tragedy, but with a difference: here, Superman really could have been everywhere at once. With all the resources available to him, he could have done something, but ultimately he was too immature to realize it.

The lesson Clark learns from his personal tragedy informs his outlook as Superman throughout the film, moreso than the conversations he has with Marlon Brando’s Jor-El, who tells Clark to “control” his “feelings of vanity.” Pa Kent’s death even makes Missus Tessmacher’s ill-intentioned heroism look good by association: she’s physically attracted to Superman, so she helps him stop California from falling into the Pacific Ocean. Director/co-writer Richard Donner knew exactly who his Superman was, and it shows in the scene where Reeve’s Clark delivers a phrase as corny as, “Truth, justice, and the American way” and makes it stick. (Donner’s take has informed many subsequent Superman comics. For example, in Secret Origin, writer Geoff Johns’s homage to the first of Donner’s two Superman movies, artist Gary Frank’s Clark is modeled after Reeve’s incarnation of the character.) The 1978 film’s comedic interludes aren’t always successful, but Superman: The Movie is otherwise a funny and dynamic movie about a human symbol.

5) Superman: The Animated Series (1996-2000)

After the runaway success of Batman: The Animated Series, show-runners Alan Burnett, Paul Dini, and Bruce Timm, were asked to repeat that show’s success for a Superman television show. Superman: The Animated Series never got the critical love it deserved, but the show’s creators really got what makes the character great. Timm worked extra hard, knowing that he had to be a credible symbol of hope without seeming too “cornball.” In a 2004 interview with Modern Masters, Timm said: “[Superman] doesn’t make as much sense in the modern world as he did when he was first created. Times have changed and he means something different now than he did way back then. The context of the character is different. So you had to find ways to keep him true to the spirit of the comic and the spirit of the character, but at the same time not let him become a cornball anachronism. That was kind of tricky.”

Timm’s greater efforts paid off in many little ways, all of which contribute to the sense that The Animated Series‘s Superman exists in a fully-realized environment. First, Timm’s Superman stands apart visually. He doesn’t look or talk like any previous Supermen, from the Max Fleischer cartoon version to Christopher Reeve’s live-action icon, because he’s partly modeled after old Hercules cartoons Timm stumbled upon. Next, the show’s villains really stand apart. While Timm concedes newly revamped villains like the Toyman are more like Batman villains, he did do a great job of tweaking the existing orgins of other Superman villains such as the Parasite, a schlubby janitor who becomes obsessed with absorbing Superman’s powers after being exposed to toxic chemicals. And the show’s voice actors are consistently exceptional, particularly Brad Garrett’s Lobo, Gilbert Gottfried’s Mr. Mxyzptlk, Bud Cort’s Toyman, and Ron Perlman’s Jax-Ur.

Timm’s greater efforts paid off in many little ways, all of which contribute to the sense that The Animated Series‘s Superman exists in a fully-realized environment. First, Timm’s Superman stands apart visually. He doesn’t look or talk like any previous Supermen, from the Max Fleischer cartoon version to Christopher Reeve’s live-action icon, because he’s partly modeled after old Hercules cartoons Timm stumbled upon. Next, the show’s villains really stand apart. While Timm concedes newly revamped villains like the Toyman are more like Batman villains, he did do a great job of tweaking the existing orgins of other Superman villains such as the Parasite, a schlubby janitor who becomes obsessed with absorbing Superman’s powers after being exposed to toxic chemicals. And the show’s voice actors are consistently exceptional, particularly Brad Garrett’s Lobo, Gilbert Gottfried’s Mr. Mxyzptlk, Bud Cort’s Toyman, and Ron Perlman’s Jax-Ur.

The best episodes of Superman: The Animated Series acknowledge that viewers’ first impulse will always be to cynically deny that Superman acts the way he does simply because he needs to do good. It’s what makes Lex Luthor’s anti-alien ranting so chilling, and what makes the death of good guy Dan Turpin in the two-part, “Apokolips…Now!” story so affecting. Turpin’s death was borne of creative pragmatism, after all. Dini and Timm wanted to have the villainous Darkeseid kill someone just to spite Superman, but were told that they couldn’t kill a really major character like Ma and Pa Kent without reviving them later on. So Dini and Timm killed Dan Turpin, the human policeman that’s physically modeled after Darkseid’s creator Jack Kirby, but only after Turpin leads an angry mob of human protesters to stop Darkseid from killing Superman. Timm has compared this tale to Star Trek‘s series-redefining “The City on the Edge of Forever,” and with good reason. Like that episode, “Apokolips…Now!” is a milestone in its series’ development, and proof that Superman: The Animated Series‘ creators knew how to make Superman both adult- and kid-friendly.

4) “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” by Alan Moore, Curt Swan, and George Perez (1986)

When writer Alan Moore heard about a comic book tribute to Julius Schwartz, DC Comics’ highly influential Silver Age editor, Moore supposedly threatened to kill then-DC editor Paul Kupperberg unless he got the assignment. Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow is like Moore’s two other famous Superman stories in that it’s about Superman’s death. In “The Jungle Line,” Superman gets sick and must learn to accept that he’ll one day, he will die. And in “For the Man Who Has Everything,” Superman fantasizes about and rejects a life on his dead home planet, Krypton. But “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” is even more overtly about Superman’s demise. It depicts Superman’s last hours as recounted by Lois Lane, and represents everything from the public revelation that Clark Kent is Superman to a pack of supervillains’ desperate final assault on the Fortress of Solitude. Superman doesn’t know why everything is happening all at once, but he does know that this is the end for him. And in an especially affecting scene, before he fights Lex Luthor and Brainiac one last time, he cries. Moore pulls no punches here, and the impact of the scene is as moving as the death of Krypto, Superman’s dog, who heedlessly protects his master by attacking the Kryptonite Man and exposing himself to lethal amounts of radiation.

When writer Alan Moore heard about a comic book tribute to Julius Schwartz, DC Comics’ highly influential Silver Age editor, Moore supposedly threatened to kill then-DC editor Paul Kupperberg unless he got the assignment. Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow is like Moore’s two other famous Superman stories in that it’s about Superman’s death. In “The Jungle Line,” Superman gets sick and must learn to accept that he’ll one day, he will die. And in “For the Man Who Has Everything,” Superman fantasizes about and rejects a life on his dead home planet, Krypton. But “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” is even more overtly about Superman’s demise. It depicts Superman’s last hours as recounted by Lois Lane, and represents everything from the public revelation that Clark Kent is Superman to a pack of supervillains’ desperate final assault on the Fortress of Solitude. Superman doesn’t know why everything is happening all at once, but he does know that this is the end for him. And in an especially affecting scene, before he fights Lex Luthor and Brainiac one last time, he cries. Moore pulls no punches here, and the impact of the scene is as moving as the death of Krypto, Superman’s dog, who heedlessly protects his master by attacking the Kryptonite Man and exposing himself to lethal amounts of radiation.

Still, as strong as Moore’s script is, it’s obvious why Moore jumped at the chance to collaborate with legendary Superman artist Curt Swan. He gave Swan the room he need to show off his crisp, clean-line style. Swan worked with panels that were much bigger than the kind that typically confined him while working under editor Mort Weisinger. He really flexes his creative muscles in a page like this, no longer bogged down by breathless word balloons and blocky captions.

The fact that Swan’s drawings evoke a particular era in Superman’s history adds a fittingly surreal element to Moore’s story. “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” is essentially an “imaginary story,” a kind of stand-alone tale that took place in an alternate reality and didn’t affect mainstream Superman comics’ ongoing storylines. Swan drew some of the more memorable imaginary stories, including, “Why Superman Needs a Secret Identity,” in which Superman’s parents are killed and he’s attacked outside his own apartment because he stupidly revealed his identity at a young age. By the time “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” was published, Swan’s style made Moore’s sophisticated homage look like an ode from another world, one in which Superman’s childhood audience grew up and learned to accept that even a symbol can die.

3) All-Star Superman, by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely (2005-2008)

Not to be outdone by Alan Moore, writer Grant Morrison created a funny, moving testament to Superman’s longevity with the help of frequent collaborator Frank Quitely. Morrison’s story is, incidentally, also about Superman’s death. After flying too close to the sun, Superman is informed that he’s absorbed too much yellow sunlight and could perish at any moment. In the time he has left, Superman writes a will, revisits Smallville, tries to empathize with Lex Luthor, romances Lois Lane by giving her super-powers for a day, and completes 12 Herculean labors.

Morrison takes time to highlight the supporting characters he feels best define Superman’s legacy, from Pa Kent to the Superman Squad, a team of Supermen from across time and space. So All-Star Superman #4 is about Jimmy Olsen, whose history of finding trouble and transforming into everything from a genie to a giant turtle monster is chronicled in Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen (1954-1974). And All-Star Superman #5 is all about Lex Luthor, who delivers a long-winded anti-Superman monologue to Clark Kent from a death row prison cell. Morrison is characteristically ominivorous in his influences, peppering his story with references to everyone from Doomsday, the villain that killed Superman in the “Death of Superman” story arc, to Atlas and Samson, fellow Gods that jovially tormented Superman in “The Three Super-Enemies”, “Superman Vs. Atlas” and other Golden Age stories.

But All-Star Superman is as fantastic as it is because it none of its characters’ actions happen in a vacuum. Instead, everyone exists in their own compartmentalized little worlds. While plenty of people witness Clark Kent’s clumsy habits, no single person understands what motivates him; so it’s not shocking when, in issue #5, Lex Luthor tells Clark Kent, “you write like a poet, but you move like a landslide.” Luthor’s so blinded by his own genius that he doesn’t notice that Clark is constantly saving him from killing himself, even during a prison riot caused by the Parasite. Likewise, in All-Star Superman #4, Perry White, Clark’s editor at the Daily Planet, has a delayed double-take when Clark says “Oh, my land!” and then rushes out of his office. (Perry’s response is priceless: “Oh my what?!”) Even Lois can’t see Superman for who he is, refusing to believe him when he says in #3 that he is, in fact, Clark Kent. Morrison wants his readers to be dazzled by his characters’ numerous identities. All-Star Superman celebrates the character’s many past lives, and insists that Superman can never really die since he’s already an immortal archetype.

2) Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen by Jack Kirby (1970-1972)

The first series Jack Kirby took on after officially returning to DC Comics’ staff was Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen. At the time, the title’s sales were in serious decline. And while creators ranging from John Byrne to Bruce Timm have since acknowledged how much they were influenced by Kirby’s style, few recognize that Kirby introduced some of his most innovative characters in Jimmy Olsen, a title that until 1970 had been mostly drawn by the great Curt Swan. Jimmy Olsen was the first Superman-related ambassador to meet the New Gods, a flamboyant pantheon of heroes and villains that lived in Kirby’s mythic Fourth World. Soon such characters as Darkseid and Mr. Miracle would be regularly associated with Superman, if only because they, like he, were nigh-omnipotent.

The main difference between the New Gods and Superman is that, like Marvel’s Thor, Superman cares about humanity. In contrast, the New Gods treat Earth like a battlefield for their never-ending personal squabbles. So while Superman can mingle with the New Gods, he can never fit in with them because he’s Clark Kent first, Superman second. Still, in these early Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen stories, Kirby tinkered around with a number of wild ideas. When he wasn’t having Superman team-up with Don Rickles (twice!), Kirby introduced the Hairies, a group of technologically advanced hippies, and revived the Newsboy Legion, a pack of newsies Kirby first introduced in 1942.

Since Jimmy Olsen was already on the skids, Kirby didn’t need to work too hard to boost sales. But he still worked tirelessly to make his more outre ideas viable enough to sustain their own series. Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen was the back door Kirby used to admit Darkseid, one of his most famous villains, into the DC universe. This was no small feat. Darkseid was originally modeled after Jack Palance and Hitler, and the architecture of Apokolips, Darkseid’s hellish, Nazi-Germany-by-way-of-an-industrial-plant homeworld, is equal parts brutalism and futurism. Kirby continued to develop Apokolips and the Fourth World over the next couple of years in titles like The Forever People and Mr. Miracle. But the New Gods association with Superman and Jimmy Olsen would continue for decades, in such titles as Jim Starlin’s Death of the New Gods and the Grant Morrison-scripted Final Crisis.

1) Superman Cover Art as Drawn by Curt Swan (1948-1970)

While John Byrne, Jose Luise Garcia-Lopez and many other artists have put their own unique stamp on Superman, none have proved as influential as Curt Swan. As inked by George Klein, Swan’s streamlined depiction of the character now epitomizes Superman in the Silver Age. Postmodern writers such as Alan Moore and Grant Morrison worship Swan’s Superman because his vision of the character is defined by possibility. Swan’s Superman has a classic look, but his identity otherwise changes from story to story. Swan’s Superman stories usually revolve around incredible transformations or role-reversals that are resolved within the brief span of an issue. Al Plastino drew the interior art for the stories, including the memorable “Invasion of the Super-Ants,” in which a mutated Superman leads a horde of ants into the Daily Planet‘s offices; but it’s Swan’s cover for that issue that’s remembered.

Swan’s cover art is so striking that it’s sometimes disappointing to pick up a collection of Action Comics reprints and discover that Swan only drew covers for such gems as “The Kryptonite Killer,” a bizarre Lex Luthor-centric adventure where the bald villain escapes a planet of robots with help from lead, diamond, and Kryptonite-based automatons that he invented. But DC Comics’ editors know that people read Showcase collections for Swan and especially love his covers; that’s why Swan and Klein’s cover art is listed in the table of contents alongside writer credits for Otto Binder and interior art by Al Plastino.

Swan’s cover art is so striking that it’s sometimes disappointing to pick up a collection of Action Comics reprints and discover that Swan only drew covers for such gems as “The Kryptonite Killer,” a bizarre Lex Luthor-centric adventure where the bald villain escapes a planet of robots with help from lead, diamond, and Kryptonite-based automatons that he invented. But DC Comics’ editors know that people read Showcase collections for Swan and especially love his covers; that’s why Swan and Klein’s cover art is listed in the table of contents alongside writer credits for Otto Binder and interior art by Al Plastino.

Swan’s indelible covers are a good part of why he’s the artist most closely associated with imaginary stories like, “Lois Lane, the Super-Maid of Krypton,” a Lois Lane yarn that speculates about what might have happened had Lois was rocketed to the planet Krypton and given Superman-like powers. Swan’s Superman is a seamless combination of cartoon-like dynamism and experimental formalism. While Swan did also briefly draw the Superman newspaper strip, he excelled at page-length splash panels like the one that opens “The Man Who Betrays Superman’s Identity.” Here, Perry White mulls over a multi-paneled, life-sized poster of various men he suspects could be Superman’s alter-ego, everyone from Clark Kent to Rod Serling sound-alike Rand Sterling. And in “The Superman Super-Spectacular,” Swan really gets to show off his skills as a sequential artist. The panels are bigger, and Swan’s art breathes more as a result.

The bigger Swan’s Superman got, the more room Swan had to develop him into a bigger-than-life question mark. Superman in the Silver Age could be anything at any time, making Swan’s take on the character accidentally emblematic of the spirit of weird transformation that would usher the character from the post-war ’50s, through the radical ’60s, and into the decadent ’70s. If Superman perennially changes, as the title of Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale’s Superman for All Seasons implies, then Swan’s is the Superman of spring: a season of radical growth and brash rebirth.

Simon Abrams is a native New Yorker and freelance film critic whose work has been published by Esquire, The Village Voice and Press Play, where he wrote “Ten Bat-Takes: The Ten Best Interpretations of Batman.”