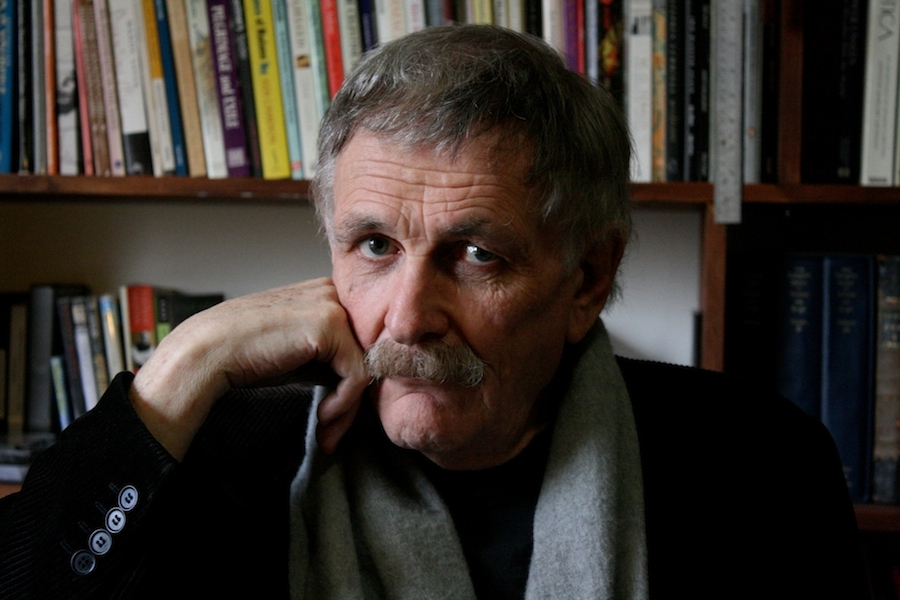

Paul Cox, whose cinematic meditations on love, art, solitude and mortality made him a favorite both in international film circles and the Ebertfest community, has passed away at the age of 76. The director of such international favorites as “Man of Flowers,” “A Woman’s Tale” and “Innocence” once remarked in an interview, “To also realize we’re going to die one day, to ask questions about death is very important because that makes you more alive and it makes you more of a decent human being.” Throughout his career, he constantly asked questions about death, life and love. As a cursory glimpse of his filmography can attest, his willingness to ask these questions made him both an excellent filmmaker and, as anyone lucky enough to have met him can attest, a more-than-decent human being.

He was born Paulus Henrique Benedictus Cox in the Netherlands on April 16, 1940 and did not actually arrive in Australia until 1965, by which time he had already established himself as a photographer who would go on to publish three collections of his photos over the years. After his arrival, he began working on his first short film, “Matuta: An Early Morning Fantasy” (1965) and over the next decade, he would make several more short films while also teaching at the Prahran College of Advanced Education. In 1976, he made his first feature, “Illuminations,” which told the story of a woman preoccupied with death in the wake of her father’s passing who discovered a new-found zest for life following her own near-death experience. The film, inspired by a dream Cox had, would also prove to be significant because it marked his first collaboration with actor Norman Kaye, who would work together on a total of 16 films over the years until the actor’s battle with Alzheimer’s ended their collaboration. (Cox would pay tribute to the actor with the 2005 documentary “The Remarkable Mr. Kaye.”)

“Illuminations” was followed with 1978’s “Inside Looking Out,” a depiction of a week in the life of a collapsing marriage. In 1979, he directed “Kostas,” the story of a Greek taxi driver, and though it was the least personal of his works thus far, it was his most acclaimed film at that time. In 1982, he had his first big breakthrough with “Lonely Hearts,” a charming romantic drama in which a forlorn middle-aged man (Kaye) joins a dating service and is brought together with a shy bank clerk (Wendy Hughes). A lovely and quiet miniature, it went on to win the Australian Film Institute’s prize for Best Picture and became his first film to break through onto the international scene.

He would score an even bigger breakthrough the next year with what many (including this writer) consider to be the finest work of his career, 1983’s “Man of Flowers.” In this film, Norman Kaye plays an eccentric old man who revels in the erotic sensations that he feels when observing flowers, art and, most significantly, a young woman (Alyson Best) who undresses before him while classical music plays in the background. I realize that this brief description may make it sound like a creepy sexploitation effort at best, but it really is one of those films that defies description. There are many films that depict erotic behavior but this is one of the few that tries to explore it without merely devolving into a peep show. “Man of Flowers” went on to become a hit around the world but viewers certainly got more than a mere eyeful, including an unforgettable performance by Kaye that won him the AFI Best Actor award.

Although Cox would use elements taken from his life in most of his films, his next two projects would be especially autobiographical in nature: “My First Wife” (1984) was a drama inspired by the dissolution of his own marriage; “Cactus” (1986) took its inspiration from Cox’s mother’s bout with temporary blindness and told the story of a woman with an eye injury who begins a romance with a young blind man. Having contemplated it for years, Cox reconceived it as a project for the great French actress Isabelle Huppert, a move that would eventually lead to a split with longtime writing collaborator Bob Ellis, who disagreed on the idea of centering the film on a Frenchwoman visiting Australia. Following that, he shifted focus with “Vincent” (1987), a stunning documentary on Vincent Van Gogh that tells the painter’s story through letters that he wrote to brother Theo and which remains arguably the best film made to date about the man and his work.

In 1989, he teamed up with actress Irene Papas for “Island,” the story of a Czech woman who comes to the Greek islands to sort through her personal problems. “Golden Braid” (1990) was an adaptation of a Guy de Maupassant short story in which a man finds a braid in an antique clock and becomes obsessed with his fantasy of the long-ago romance that led to it being put there. Neither of these films were that notable but that was not the case with his next film, “A Woman’s Tale” (1991), which looked at the last days in the life of an elderly cancer victim played by Sheila Florance. As it turned out, Florance herself was dying of cancer while filming and would pass away a mere nine days after receiving the AFI Best Actress award. However, even if you aren’t familiar with the backstory, it is impossible not to be moved by this simple and direct look at a woman facing her mortality that avoids all the expected cliches and is all the better for it. There have been many films over the years dealing with people bravely facing terminal illnesses and, simply put, this is one of the best and truest that I have ever seen.

For his next two films, he would adapt novels by author E.L. Grant Watson. “The Nun and the Bandit” (1992) told the story of two brothers whose kidnapping of a rich younger cousin is messed up when her nun chaperone insists on coming along as well—although Cox was satisfied with the film, it ended up going direct to video in Australia. 1994’s “Exile” was a religiously-tinged drama about a young man banished to a remote island for the crime of stealing sheep. In 1996, there was “Lust and Revenge,” a comedy-drama focusing on commercial and erotic temptations centered around the art world. “Molokai: The Story of Father Damien” (1999) was a straightforward biopic about the Belgian priest (played by David Wenham) who famously tended to the lepers on the island of Molokai, Hawaii. During this time, Cox also published the book “Reflections: An Autobiographical Journey.”

With his next effort, “Innocence” (2000), Cox would have one of the biggest critical and commercial successes of his entire career. This film told the story of two elderly people (Julia Blake and Bud Tingwell) who happen to meet again more than forty years after the abrupt ending of their youthful romance and embark on a second affair. Yes, the premise makes it sound like a sort of Hallmark TV movie, but in Cox’s expert hands, there is not a tinge of mawkishness to the proceedings. As depicted here, the reignited romance is as raw, reckless, painful and ultimately convincing as any screen love story that you could name. If this obituary inspires you to go and seek out Cox’s films, this is probably the one that you should begin with.

With “Nijinsky: The Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky” (2001), Cox came up with a companion piece to “Vincent” that looked at the life of the famed dancer that combined footage of dancers at work with readings from Nijinsky’s diaries read by Derek Jacobi. 2004’s “Human Touch” told the story of a woman (Jacqueline McKenzie) who embarks on an unexpected journey of self-discovery after she agrees to pose nude for an artist to help raise money for her choir to travel to China. “Salvation” (2008) looked at a scholar whose unhappy marriage to a televangelist inspires him to drift into an unexpected relationship with a Russian immigrant working as a prostitute.

In 2009, Cox was diagnosed with liver cancer and at one point was given only six months to live. Happily, not only did he get a new lease on life thanks to a liver transplant, he met fellow transplant recipient Rosie Raka and she became his partner. These experiences would be chronicled by filmmaker David Bradbury in the 2011 documentary “On Borrowed Time” and would later form the basis for what would prove to be Cox’s final feature, “Force of Destiny” (2015). In that film, David Wenham played a sculptor awaiting a liver transplant who finds himself falling in love with an Indian marine biologist (Shahana Goswami) whose uncle is also dying of cancer. Given the circumstances, one might have expected a certain mawkishness to the material but in exploring his own extreme circumstances, Cox proved to be just as honest and direct as he was with his other cinematic subjects.

Of all the filmmakers who have come to Ebertfest over the years, he may well be the one who has connected most strongly with the festival and its basic ideals. He would appear no less than six times, the last being with the U.S. premiere of “Force of Destiny.” Each time he appeared, he would enthrall, entertain and move the audiences, both with the power of his cinematic vision, and the simple but heartfelt humanity that he displayed both during the various Q&A’s and panels that he took part in, along with in his interactions with other festival visitors. His passing is a loss both to the film world and the Ebertfest community in particular and he will be deeply missed.

To read Roger’s reviews of Paul Cox’s films, click here