Among the stars of the 1930s and ’40s, Stanwyck stands out as one of the few who could walk onto a movie set today—or fifty years from today—and still seem utterly modern.

One reason is the ease with which she slips into the role of the woman who knows what she wants and how to get it. While she was superb in an astonishing range of films from wild comedy to romantic drama and the darkest noir, she was at her best playing independent, confident women who knew how to make the best of their situations. She could play vulnerable (“Executive Suite”) and neurotic (“Sorry, Wrong Number”). She played women who had the power to persuade men to murder (“Double Indemnity“), cover up a murder (“The Strange Love of Martha Ivers”), or hide her from the police (“Ball of Fire”). But she played women who, like Stanwyck herself, had to learn how to take care of themselves and were very good at it.

In “Stella Dallas,” one of Barbara Stanwyck‘s signature roles, the actress plays a lower-class woman who gives up her daughter, Laurel, so the daughter can have a chance at a better life with her wealthy father and stepmother. In the heartbreaking final scene, Stella looks through a window in the rain to get a glimpse of Laurel on her wedding day. She is literally an outsider at her own daughter’s wedding. Instead of giving Laurel away or hosting the reception, she is a spectator, and only for a moment at that, shooed along by a cop. Even so, she asserts her authority, insisting that the policeman let her take one more look.

More significantly, Stella has been in charge all along. She has orchestrated her daughter’s life for just this moment. Stella herself once had hoped to join the upper class. But she realizes she could never fit in. Later, realizing that her lack of refinement makes her a social liability for Laurel, Stella persuades her that she does not want her anymore and sends her to live with her new stepmother so that she can be a suitable match for the wealthy boy she wants to marry.

As she leaves the window, Stanwyck’s face shows mingled tears and rain, loss and triumph.

We see Stanwyck calling the shots again in Preston Sturges’ romantic comedy, “The Lady Eve.” Seated in the dining room of a luxurious ocean liner, she uses the mirror in her compact to monitor the clumsy efforts of the other young women on board to capture the attention of the shy young heir to the Pike ale fortune played by Henry Fonda. We watch with her through the mirror as she provides a running commentary on their ploys: “Holy smoke, the dropped kerchief! That hasn’t been used since Lily Langtry. You’ll have to pick it up yourself, madam.” Then, when he tries to leave, she sticks out one of her lovely legs and trips him, the first of several times she will cause him to fall on his face as she stays in charge right up to the last scene, back on the ship.

In a scene cut from the 1934 pre-Code “Baby Face” and not restored until 2004, Stanwyck’s character gets some advice from a Nietzsche-loving cobbler that could be the framework for many of the characters she would play over the next three decades: “A woman, young, beautiful like you, can get anything she wants in the world. Because you have power over men. But you must use men, not let them use you. You must be a master, not a slave. Look here—Nietzsche says, ‘All life, no matter how we idealize it, is nothing more nor less than exploitation.’ That’s what I’m telling you. Exploit yourself. Go to some big city where you will find opportunities! Use men! Be strong! Defiant! Use men to get the things you want!” In that film, unforgettably, Stanwyck’s character literally sleeps her way to the top, the camera tilting up outside of the office building as she seduces wealthier and more powerful men on higher and higher floors until she reaches the penthouse.

Like Stanwyck herself, most of her characters talked like they came from Brooklyn, even the faux “Lady Eve.” “I can be as English as nessisry,” she says airily, and apparently that does not require an authentic-sounding English accent, which of course adds to the fun. While many of the actors of her era affected the mid-Atlantic accent of the legitimate theater, which now sounds dated to our ears, Stanwyck never sounded like anyone but herself, and imperishably contemporary.

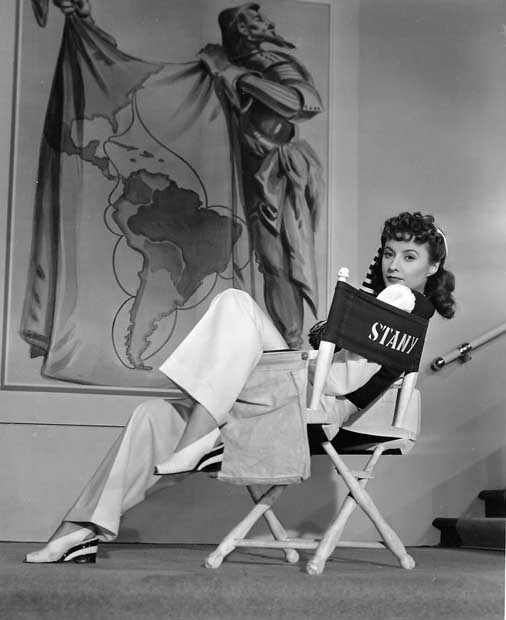

She was the consummate professional, always prepared and always first to the set. On “The Bride Walks Out,” where Stanwyck plays a woman who secretly keeps working after her husband wants her to quit, Robert Young said he kept coming earlier and earlier to try to get there first but he never beat her. She always knew not only her lines but everyone else’s, plus all of the set movements and blocking, whether she was in the scene or not. “I have to know everything from the very start,” she said. That gave her the freedom to focus on her performance. She was drilled in technique by stage directors early in her career, but she was made for close-ups on screen. “Acting is thinking,” she said. On the advice of theatrical producer David Belasco, she went to the zoo to watch panthers for hours so she could adopt their slinky movements. Pauline Kael would later praise her “intuitive understanding of the fluid physical movements that work best on camera.”

The actress began to learn about creating a character from creating her own persona. She played women who could take care of themselves because she had to do that all her life. She was born Ruby Stevens on July 16, 1907. Her parents died when she was young and she lived with several foster families. At age 17 she joined the Ziegfeld follies. She stripped behind a screen. Dubbed Barbara Stanwyck by a producer, she asked how to spell it as she signed it for the first time, on a contract.

In the first of a new two-volume biography, A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940, Victoria Wilson writes that Stanwyck was “outside the protection of a single studio that built actresses and created them to last, that provided movies one after the other, shaped publicity, created a single look, and sold the image. [She] wasn’t protected by that sense of belonging or reassured by it. She found it a constraint.”

Stanwyck insisted on an unprecedented level of control over her own career, even in the heyday of exclusive contracts that forced actors to appear in whatever films were assigned by studio bosses. Working with her agent Zeppo Marx (of the Marx Brothers), she insisted she would never appear as “the girl” in a film. She made sure that the characters she played would be tough, independent, and a key focus of the storyline. They were always good at their jobs, though not always so capable outside of the office. In “Christmas in Connecticut,” Stanwyck plays a Martha Stewart-style columnist who does not have the cooking skills or New England farmhouse or family she writes about so evocatively. When her editor orders her to invite a serviceman to an old-fashioned country Christmas on her farm, the kitchen scene in the borrowed country home is charmingly chaotic. In that film and others—including “Baby Face,” “Ball of Fire,” “The Lady Eve,” and “Remember the Night”—she played self-reliant, often cynical women who learned to love and be loved. Wilson quotes Stanwyck’s close friend, Zeppo Marx’s wife, Marion, who could be describing the essential modernity of the characters Stanwyck played as well as the woman herself: “natural, unaffected; as straightforward as a man; not like many glamour queens.”