We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the latest edition of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. This month, in honor of #Bergman100, and Criterion’s upcoming release of a 30-disc box set of his work, they’re devoting their entire November issue to the films of Ingmar Bergman, looking to bring new & diverse perspectives to the legendary Swedish auteur’s work. In addition to Ethan Warren’s “Hour of the Wolf” piece “The Tumult Breaks Loose” below, they also have new essays on “Scenes from a Marriage,” “Cries & Whispers,” “Persona,” “Fanny & Alexander,” “The Passion of Anna,” “Face to Face,” “Summer with Monika,” “The Magic Flute,” “It Rains on Our Love,” and an intimate, in-depth interview with frequent Bergman collaborator Liv Ullmann.

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here

Eighty-five miles off the coast of Sweden lies the island of Fårö. With a population of around 500 and an area of under 45 square miles, this is, in the words of a 2016 New York Times profile of the region, “Where Swedes go to be (really) alone.”

The shoreline of Fårö is dotted with rauks, stone stumps that were once grand arches before they were attacked by the elements. The wind and the surf would drive against the arches until cracks formed, and once those cracks were there, it was only a matter of time until one half of the arch could no longer sustain itself and collapsed into the sea. The other half of the arch might manage to stay upright for a while, but without its supporting half, it too would crumble, leaving behind just a rauk.

Fårö has no bank, no post office, no police force. “It can feel dangerous to be alone in the country for long,” Christine Smallwood wrote in that New York Times profile. “Being alone is a sign that something is about to go wrong, perhaps catastrophically so.”

And in 1968, it was here that Ingmar Bergman chose to tell his most horrific tale.

*

Hour of the Wolf is the story of a marriage crumbling in a void. Johan and Alma (Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann, the ultimate Bergman power couple) have traveled to their remote island cottage to spend the season, but as we know from an opening title card, Johan will be gone long before the season is through.

Johan is a painter of some renown, but his professional success masks a turbulent inner life. As we’re told by Alma in a prologue delivered straight to the camera, Johan has a history of anxiety and paranoia. He can’t sleep at night—particularly not during “the hour of the wolf,” that predawn hour, as he explains, when nightmares become real—and he’s pestered by strange supernatural figures that he calls “flesh eaters,” drawing them compulsively until they’ve overflowed his sketchbook.

Johan is, in the old-fashioned literary sense of the word, mad. Bergman elides any proper diagnosis in favor of a more poetic depiction, the tormented artist as fairy-tale figure. And as you might expect of a storybook nightmare, it’s not long before Johan’s madness is made flesh. The demons step out of Johan’s sketchbook and present themselves as grotesque aristocrats who wine and dine Alma and Johan at their gothic castle. They menace Alma and flatter Johan, digging their claws into the cracks in this marriage until they’ve torn it apart. By the end of the film, Johan has abandoned Alma and given himself over to these physical manifestations of his madness and all its seductive promises of freedom and relief.

Hour of the Wolf is often cited as Bergman’s one true foray into the horror genre, and the surreal hysteria that awaits Johan in his climactic visit to the castle is absolutely unnerving—a woman removes her face and drops her eyeballs into cocktail glasses; a man walks onto the ceiling while another grows wings. To me, though, the horror stories it calls to mind are the ones where a monster is loose in the house—except here the house is a marriage, and the monster wreaking havoc is Johan’s instability, a festering rot borne of his secrets and regrets. And that kind of psychic monster can’t be kept at bay for long. Soon enough, “the tumult breaks loose.” That line comes from the climax of the published version of Hour of the Wolf included in Bergman’s 1972 book Four Stories; it’s spoken by Alma as she cowers in the forest watching Johan’s demons tear him limb from limb. This denouement is entirely reconceived from page to screen; in the most significant shift, Bergman’s text has the demons badger and taunt Johan as they rip at his flesh, hurling contradictory commands (“Keep standing, don’t be afraid! Lie down and it will be quicker”), taunts (“Can’t you take a joke?”), and nauseating boasts (“He can’t talk because I’ve made mincemeat of his tongue”). In the film, the dismemberment is punctuated only by avant-garde sound effects.

That line comes from the climax of the published version of Hour of the Wolf included in Bergman’s 1972 book Four Stories; it’s spoken by Alma as she cowers in the forest watching Johan’s demons tear him limb from limb. This denouement is entirely reconceived from page to screen; in the most significant shift, Bergman’s text has the demons badger and taunt Johan as they rip at his flesh, hurling contradictory commands (“Keep standing, don’t be afraid! Lie down and it will be quicker”), taunts (“Can’t you take a joke?”), and nauseating boasts (“He can’t talk because I’ve made mincemeat of his tongue”). In the film, the dismemberment is punctuated only by avant-garde sound effects.

That was the right choice. The demonic chant is pleasantly disturbing, but those impressionistic bursts and shrieks are so much more accurate; when your madness is having its way with you, it’s impossible to convey in words the havoc being wreaked upon your mind.

*

My own tumult broke loose in the spring of 2011. Just before my 25th birthday, I slipped into a manic episode with psychosis. For a week, I cycled from howling rage to howling sorrow, operating on increasingly erratic impulses as my rational self was devoured by a hyperactive id, one powered by incessant emotional neediness and savage retaliative force.

The primary witness to my breakdown was my girlfriend, Cait. We had met in college four years earlier in the kind of old fashioned story you’re not even supposed to hope for in the 21st century—she was the beautiful clerk at the school store; I had a massive crush and visited every day for weeks, buying things I didn’t need just so I could exchange a smile and a pleasantry while I worked up the nerve to introduce myself.

By 2011, Cait was spending most nights at my apartment near Harvard Square, so as my hours of sleep and my interest in food decreased, she was the one watching with mounting anxiety, and as my grip on reality crumbled, she was the one bearing the brunt of my flourishing paranoia. While my friends received alarming phone calls and it was my family who drove me to the hospital when it became clear there was no other option, Cait was the one beside me every morning and evening. She was the one in the eye of the storm, tasked every night with convincing me to stop ranting long enough to eat even one bite, saddled with my belligerent calls and texts throughout her work day. And when it all started falling down around me, it was Cait I punished.

I spent years dragging my way back to something resembling emotional equilibrium, but even by 2015, when Cait and I relocated to Connecticut so she could attend nursing school, my trauma and grief was too raw to touch with anything but the briefest remembrance. And living hours from my friends with a girlfriend who worked multiple overnights a week at the hospital, I turned to movies to give my life shape. I gorged myself, consuming anything I could put in front of my eyes. And so one night, I found myself watching Hour of the Wolf for the first time.

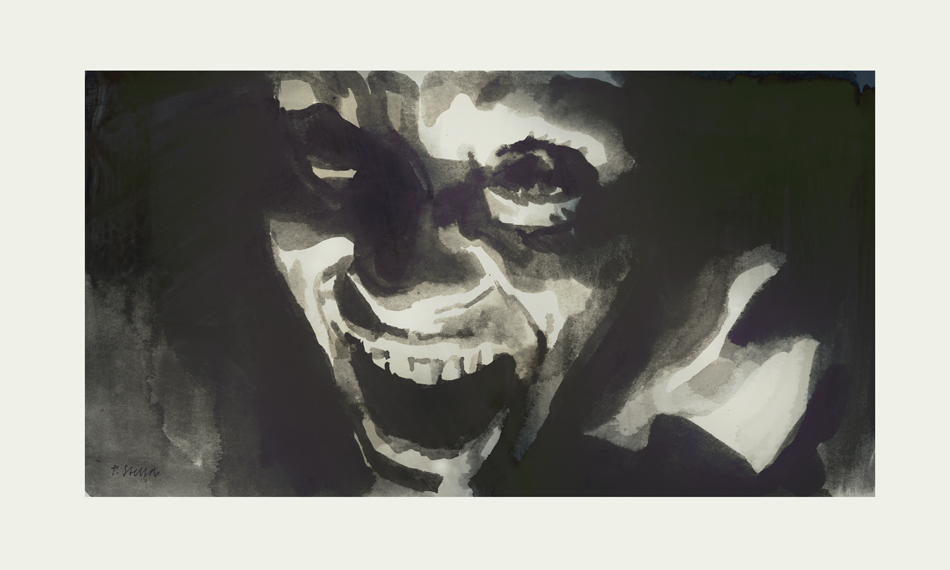

I knew nothing about the film, I was simply seduced by a cover depicting a shadow-drenched face shrieking with what might be maniacal laughter, mortal terror or both. I was no stranger to Bergman’s visions of terror, but as they tended to lie in the theological (the “Silence of God” trilogy) or cerebral realm (Persona and The Passion of Anna, two more Fårö stories of crumbling psyches), I was tantalized by the promise of the master stripped of any enigmatic subtlety. I wanted Bergman with the gloves off.

I forgot to be careful what I wished for. Hour of the Wolf hit me with brutal force, leaving me gasping and reeling as I struggled to process a story that was simultaneously alien and shockingly familiar. In Johan’s struggle to maintain a grip on his sanity in the face of his demons’ temptations, I recognized how easily I’d succumbed to my own worst urges, and the horrors that lay in store once I’d given myself up. Most painful was the scene in which a demon invites himself into the cottage and politely places a handgun on the table between Johan and Alma. The demon claims that he wants Johan to be able to defend himself from the island’s small game, but the metaphoric implication is clear: the forces of madness have offered the tool to conclusively sever any connection to the tedious responsibilities of sanity.

Most painful was the scene in which a demon invites himself into the cottage and politely places a handgun on the table between Johan and Alma. The demon claims that he wants Johan to be able to defend himself from the island’s small game, but the metaphoric implication is clear: the forces of madness have offered the tool to conclusively sever any connection to the tedious responsibilities of sanity.

Out of any damage that I did during my psychosis, the memory that still ached the most years later was of the night before I was hospitalized. Supercharged with the raging energy of a collapsing star, I took a gentle plea from Cait—“You don’t seem like yourself and I’m getting scared”—as an excuse to unload a torrent of wrath. When my madness pressed that weapon into my hand, I used it without a second thought. Though my memories of the night remained hazy, what lingered was the feeling that I had wanted to destroy the only woman I’d ever loved. And then, just like Johan, I had surrendered to my madness, and all the freedom it had promised had been revealed as a lie.

Bergman had held up in my face, with stark, monochromatic objectivity, everything that had happened to me, a tangle of trauma I could barely organize enough to begin processing. For years afterwards, I would remember Hour of the Wolf as my own personal cracked mirror. But it would be years before I could really begin examining the same question that Johan asks when his demons show him his shattered visage: “What do the shards reflect?”

*

Alma’s greatest desire is to merge her life completely with Johan’s. On one of the long nights that she stays awake to keep her husband company, she muses, “I hope we become so old that we share each other’s thoughts.” This is no typical intimate union she wishes for; she yearns to become indistinguishable from her husband, even physically.

It isn’t her choice to sit up all night. “You have to stay awake awhile,” Johan has barked moments earlier. “Talk to me, Alma.” But he hides his face as she speaks, either unwilling or unable to engage. On first viewing, I felt Johan’s pain. But when I returned to the film two years later, I was startled to see the callousness in the gesture, a husband piling onto his wife the full weight of the night’s emotional labor.

Cait and I had been married nearly two years when curiosity, possibly half-masochistic, brought me back to Hour of the Wolf. I put it on late one night while Cait and our new baby slept upstairs, and though I was wary, I told myself that I’d already absorbed the visceral impact. Now I could view the film from an academic perspective, appreciate the craft.

Once again, I underestimated Bergman’s power; a film that had once been a blunt weight had sharpened into a razor. Perhaps it was the six years of therapy that had elapsed between my breakdown and this second viewing, but where I had once been so focused on Johan’s pain, I was now shocked to recognize the abuses with which he pummeled Alma, and her pain in every scene.

Johan takes up so much air in the film—and often so much of the frame, as in the aforementioned scene where von Sydow hunches in the foreground, filling half the frame with his face, while Ullmann sits in the background cloaked in shadow—that it’s easy to see Alma as merely a supporting player in his story. But when I made the effort to see the film through Alma’s perspective, it was as though the entire plot was inverted, causing moments that hadn’t even lodged in my memory to now stand out as the most crucial. I was devastated by the scene in which Alma sits Johan down with her ledger, forcing him to listen to her studious accounting of their household purchases—if she can’t find a way to see the world through his tormented perspective, then she can at least invite him into hers. And I cringed with agony and regret at the scene’s end, when Alma weeps in the face of Johan’s indifference to her gesture.

Bergman shoots this and so many other scenes of the couple’s strained domesticity in long, still takes with no cathartic cuts to guide your emotional response, leaving you stranded in each agonizing episode of a love succumbing to entropy. But despite the staid visuals, the film shifted beneath me to reflect something I’d never fully reckoned with: yes, I had been through hell during my psychosis. But I had put Cait through hell with me, driving the vehicle towards disaster with her as the helpless passenger. At the close of the film, Alma agonizes over all her unanswerable questions. Could Johan’s destruction have been prevented if she hadn’t loved him so much? Or if she had loved him more? I had glossed over the scene before, too focused on all the trials Johan had just endured, but now I ached for Alma—why couldn’t she see herself for the blameless victim she so clearly was?

At the close of the film, Alma agonizes over all her unanswerable questions. Could Johan’s destruction have been prevented if she hadn’t loved him so much? Or if she had loved him more? I had glossed over the scene before, too focused on all the trials Johan had just endured, but now I ached for Alma—why couldn’t she see herself for the blameless victim she so clearly was?

As the screen faded to black, I thought of my week on the psych ward. I’d spent every day terrified to step into the phone booth and call Cait, unable to trust my tenuous stability enough to believe I wouldn’t lose my grip and do even more damage. When I was discharged, though, I opened my inbox to find it full of letters from her; she’d written to me every night that I was gone, even as she knew I had no access to email. She told me how much it hurt to know I was scared, and promised she’d be beside me for every step of my road to recovery. She wrote about the puppy her friends had brought over to distract her, and the therapist she had visited to make sure she was properly equipped to support me when I got home.

Reading the letters was a comfort, but it was a heartbreak, too. I had used the weapon my demons pressed into my hand, and Cait hadn’t run. How could I ever be worthy of her support again?

*

This is not the essay that I expected to write about Hour of the Wolf. I hadn’t seen the film in a year when I started organizing my thoughts, believing (in what I now should have recognized as a cycle of hubris) I finally had the film straight. I had my perspective locked down.

I expected to focus quite a bit on one scene that loomed large in my mind. In the second of Alma and Johan’s late-night vigils—which is, unbeknownst to them, the last night they’ll spend together—Alma murmurs, “It’s strange when the sea is completely calm. Scary somehow.” Seven years after my diagnosis, I still viewed my marriage as this calm sea—something that should be beautiful, but would always be defined the memory of a squall, and the question of when another might come.

When I sat down for another viewing of Hour of the Wolf, I felt secure in my understanding that this was the story of a marriage between an unstable abuser and his helpless victim. At last I could approach the film academically. But it shifted under me again, and this time that shift may have changed my life.

I waited to feel pity for Alma’s victimization, but scene by scene, something became clear: I had sold her short. Now, a bevy of holes sprang in my understanding not just of this story, but of my own. I had always wondered why in the world Alma stayed with Johan, willingly absorbing his onslaught. But as I mulled the film, I came to recognize I had robbed Alma of her agency, that in positioning her as Johan’s victim, I still viewed her through the lens of his experiences rather than seeing it as a shared narrative. And, I was ashamed to realize, I had spent years doing the exact same to my own wife.

Now, one scene that had always struck me as opaque finally became clear. As Alma and Johan walk home along the cliffs, shaken by their dinner at the castle, Alma’s pent up fear and confusion erupts. She whirls on Johan and lets him know that no matter what disaster they’re cruising towards, she isn’t going anywhere. She grabs hold of him, but her tone is defiant rather than pleading, and when she’s overcome and whirls away, she shirks his touch.

In Four Stories, Alma’s outburst is rendered from Johan’s incredulous perspective. “He realizes in a flash,” Bergman writes, “that her grief applies only to herself.” Alma is asserting her own needs, not merely pledging her devotion to him. She’s terrified of whatever might be happening to him, but just as much, she’s terrified over what might happen to her in the process. Their lives are too conjoined for his pain not to be hers as well, not just sympathetically but literally. This all may seem self-evident from an objective standpoint, but other people’s needs are a strange concept to grapple with when you see yourself as the protagonist of your nervous breakdown and interpret everyone else’s behavior through the distorting lens of your own perspective. When I managed to understand this scene—with a bit of guidance from Bergman’s prose—a tumbler fell into place in my own mind: by continually flagellating myself for what I’d done to Cait, I was casting our story as a one-way transaction rather than an interaction between two autonomous people.

This all may seem self-evident from an objective standpoint, but other people’s needs are a strange concept to grapple with when you see yourself as the protagonist of your nervous breakdown and interpret everyone else’s behavior through the distorting lens of your own perspective. When I managed to understand this scene—with a bit of guidance from Bergman’s prose—a tumbler fell into place in my own mind: by continually flagellating myself for what I’d done to Cait, I was casting our story as a one-way transaction rather than an interaction between two autonomous people.

I now saw that Cait’s letters during my time on the psych ward were as much for her as they were for me. As she noted in the first one, since the beginning of our relationship, we’d spoken every day, no matter whether we were in the same space or separated by half a world; now we were separated by only a few miles, but I’d been plucked out of her life entirely. I had always valued the letters as proof of our love, but until this most recent viewing of Hour of the Wolf, I had never really understood what it was they proved. Even if she knew I couldn’t hear it, Cait couldn’t go to bed without speaking to me. When she pledged to be there beside me as I worked towards recovery, the pledge wasn’t that she would hold me up, but that after all these years of falling deeper and deeper in love, we now leaned on one another so much that when one of us collapsed, the other couldn’t help but falter, too.

This lightning bolt shattered the essay I meant to write. But it may have just freed my marriage from almost a decade of my self-sabotaging self-pity, too.

*

Only after this last viewing did I take the time to untangle one of the stranger scenes in this strangest of films: during their visit to the castle, the demons treat Alma and Johan to a puppet production of The Magic Flute. In the scene performed for Alma and Johan, the hero, Prince Tamino, pauses during his quest to rescue his beloved, the fair maiden Pamina, from captivity. Alone and on the verge of despair, he asks two questions: Will this night ever end? And is Pamina still alive?

In his 1987 autobiography, The Magic Lantern, Bergman writes at length about his enduring fascination with this passage in Mozart’s opera. “These 12 bars,” he writes, “involve two questions at life’s outer limits.” In asking whether the night will ever end, Bergman saw Mozart as wrestling with his own existential terror as he began succumbing to his fatal illness. And in asking whether Pamina survives, Bergman argues, Tamino is really asking after the very concept of love. Bergman believes the question to be, “Is love real?” and the answer to be, “Love exists. Love is real in the world of human beings.”

There was debate following the release of Hour of the Wolf as to whether it’s Alma who stands in for Pamina in Bergman’s calculus, or whether Johan’s lost love Veronica fulfills the role, always taking for granted that Johan represented the conquering hero. Personally, I was shocked to realize anyone would see Alma as the damsel and Johan the savior. Perhaps the notion would have tracked on my first viewing, but by now it could not be clearer to me that if anyone in Hour of the Wolf is battling staggering odds to rescue their beloved, it’s Alma, and that it’s Alma who has the right to wonder whether love is strong enough to slay the forces of darkness. Johan is preoccupied with many things—primarily a lifetime of simmering guilt, regret, and shame—but the power of love does not often seem to be one of them.

After Tamino’s questions are answered, the demons are momentarily struck dumb, shaken by the affirmation. But they can’t be conquered forever. No matter how strong love is, the pain must come eventually. And it’s just a matter of perspective whether that impermanence is enough to turn a romance into a tragedy.

*

“I have this theory,” I told Cait recently, “that every love story is really a horror story.” The thought had been percolating as I mulled all these new revelations spurred by Hour of the Wolf. Nearly every story of a lifelong love, I explained, ends with one lover burying the other and being forced to endure in a world they’ve forgotten how to navigate alone. “I think the happiest ending to any love story,” I concluded, “is the old couple in Titanic lying in bed together while the ship sinks. They had a long life together and they never have to live without each other.”

I was so absorbed in my theory that it took me a moment to notice her appalled expression. “Personally,” she replied with enviable serenity, “I would rather live a few years without you and go peacefully than drown.”

It was hard to argue with that. Cait’s and my perspectives are frequently diametrically opposed; I spend my days submerged in Swedish psychodramas from half a century ago while she spends hers at a hospital helping bring new life into the world. And when we see each other at the end of the day and I tell her the fantasies I’ve cooked up in the course of my work, more than once she’s gasped, “This is what’s in your head?”

And the more I think about it, the more it seems like that might be how we survived our tumult. Neither of us has ever wished for the other’s worldview. And while any marriage is necessarily an arch formed by two people leaning on each other for mutual support, neither of us has ever so fully surrendered to the idea of us as a single unit that we couldn’t endure without the other. Because we’ve maintained that measure of distinction between us, avoiding the temptation to surrender our individuation the way Alma dreams of, then if some new tumult were to break loose and the worst befell one of us, the other might be able to stay standing and avoid becoming a rauk, an incomplete husk living on only as memorials to the past.

Though one can’t be sure, it seems unlikely that Alma will escape that fate. By the end of Hour of the Wolf, she’s so thoroughly cleft that even her sentences are severed. Trying to make sense of the trials she’s experienced, she remarks, “Sometimes, you get completely…”

But she loses the thread. She turns away, and then just before that final fade to black, she turns back to the camera, aching for an end to her agony, one it seems may well never come.