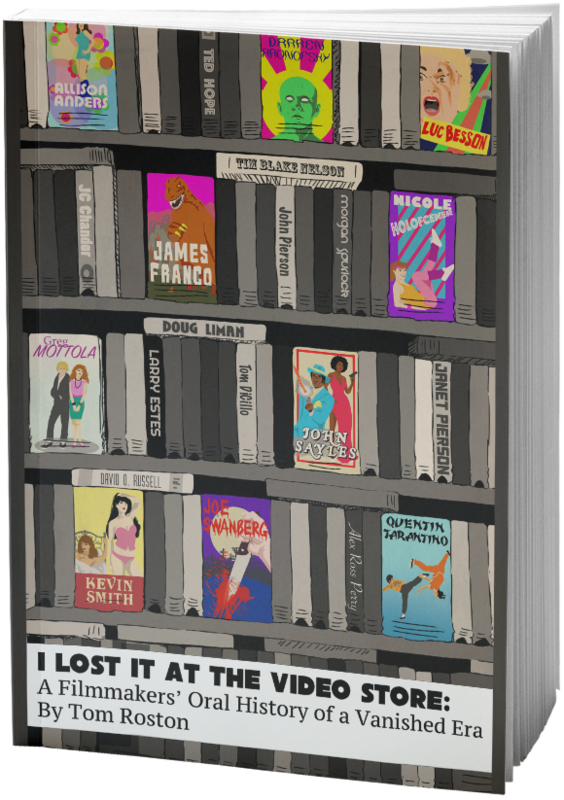

Tom Roston’s “I Lost It At The Video Store” may be the

breeziest, most engaging film book you’ll read this year. This

longer-than-usual longform oral history, published in a handsome hardcover

edition by the adventurous house The Critical Press, lets a very voluble and

opinion-generous (not the same thing as opinionated, although the border

between the two states can be unusually porous) group of filmmakers tell a

fascinating story: how the availability of movies via home video changed

cinema’s aesthetic, the movie business, and the way future filmmakers and other

artists got their educations in the craft.

Author Roston is an old colleague and an old friend; we

worked closely together at Premiere magazine from the late 1990s until the

magazine stopped publishing in 2007. A couple of things I always admired about

Tom were his commitment to Getting The Story Whatever It Took (he actually got

tattooed with Angelina Jolie while working on an early profile of the future

diva) and his ability at cultivating and maintaining meaningful

contacts/sources in the industry. It’s the second talent that serves him

particularly well here. His cast of characters, so to speak, is wide-ranging,

reasonably diverse, and pretty heavy—from Allison Anders to Quentin Tarantino, with a lot of names you want to hear from in between. It’s not just directors;

the book’s subtitle “A Filmmakers’ Oral History of a Vanished Era”

notwithstanding. Several one-time video company execs and distributors are also

interviewed. These characters, who include Richard Gladstein, whose LIVE

Entertainment was a driving force behind “Reservoir Dogs,” and Larry Estes, who

helped get “sex, lies, and videotape” made with home video money, provide what

I found to be the most interesting anecdotes about how the business of home

video provided a quantifiable shot in the arm to independent film production. I

began my career in journalism at a magazine called Video Review, so the video

store was part of my “beat” in the mid-80s; like a lot of the filmmakers

interviewed in the book, I saw firsthand the way an education via home video

could influence both a creative aesthetic and a critical one. (Video Review

actually ran a debate about “letterboxing,” as the pre-widescreen-TV practice

of preserving a widescreen aspect ratio for home viewing was called, back

before high definition was even a gleam in the eye of home theater

people.) The down-and-dirty stories

behind “Reservoir Dogs” and “sex, lies and videotape” were ones I didn’t know, even though I was aware

at the time how now-defunct semi-studios like Orion Pictures tried to exploit

“synergy” between the home and theatrical markets.

Some of the anecdotes from filmmakers who actually worked at

video stores before getting their own credits are pretty funny. Nicole

Holofcener’s tale of a store colleague with whom she didn’t get along becoming

a significant person in her subsequent life as a writer-director is

instructively mortifying. More than one filmmaker admits to an ambition of

getting his or her own “shelf” in a video store—the post-modern equivalent of

getting a retrospective at a repertory house, perhaps. I was taken with some

observations more than others; when Joe Swanberg observes that home video was,

in a sense, just another film marketing ploy, he seems to be under the

impression that he’s the first person who ever came up with that idea, of course.

And I do rather wish that Roston had gone a little further back in illuminating

the ways that the market for “adult” entertainment set a

perhaps-ultimately-unconstructive business template for the home video

business.

The oral-history format also allows a ball or two to drop,

narratively. In the chapter titled “Follow The Money,” Greg Mottola happily

recalls that the home video deal for his debut feature “The Daytrippers”

generated enough revenue that he was able “to pay everyone who worked on the movie

back.” In a subsequent quote, Tom Di Cillo says “I have never seen a dime” from

home video sales of his films “Johnny Suede” and “Living In Oblivion,” and

continues “I don’t think that this is unusual.” There’s no follow-up there, and

I would have liked one. I don’t know if that’s a question for which Roston

couldn’t get an answer, or the natural oral-history flow of “then this thing happened” would have been compromised, or what. But

this is a minor quibble.

In total, “I Lost It At the Video Store” is a really fun and edifying read

about a subject that people love to talk about. This fact was made manifest at

the book’s launch event at Book Court at the end of September. Hosted by Aaron

Hillis, who was a stalwart and inventive contributor to Premiere’s Home Guide

back when I was its editor, and who now wears many cinephiliac hats while

running one of the last surviving video stores in the tri-state area, Video Free Brooklyn, the panel featured Roston, actor/director Tim Blake Nelson,

writer/actor Zoe Kazan, and actor Paul Dano (the two are Brooklynites who are

also avid VFB customers). Director Doug Liman, another of the book’s

interviewees, showed up and was called to the panel by Roston. The freewheeling

talk was fascinating and astute (among topics touched on: how home video may or

may not have initiated a tyranny of close-ups in contemporary film style) and

suggested the topic may well be capable of yielding a sequel to Roston’s book.