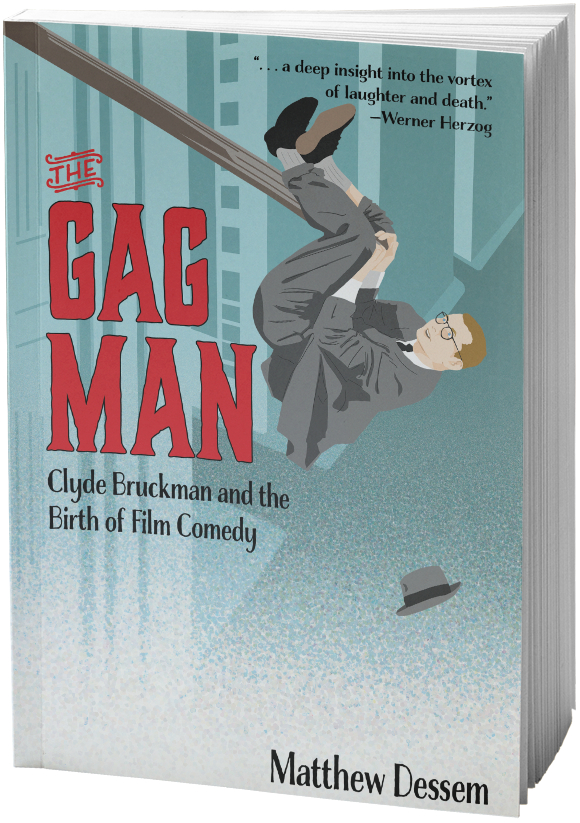

Critical Press released a book this week on Clyde Bruckman and the birth of silent comedy. We’re proud to present an excerpt below, and you can pre-order a copy of the book here.

Synopsis: Though today he is barely remembered, Clyde Bruckman was a key figure in early film comedy, collaborating with icons like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, W.C. Fields, Laurel & Hardy, and the Three Stooges. Working while screenwriting was still in its infancy, Bruckman helped shape many influential shorts and films, developed the gags that made them legendary, and eventually became a director himself. But Bruckman’s own life was filled with tragedy and disappointment, from alcoholism to accusations of plagiarism, and over time his story has been relegated to little more than a footnote.

Matthew Dessem’s The Gag Man, an expansion of his study of Bruckman for The Dissolve, will be the first book-length biography of this fascinating but elusive figure. Drawing on archives, court documents, and of course the films themselves, Dessem brings Bruckman’s story to life and shines a light on an important corner of Hollywood history.

In November of 1932, in the aftermath of his drinking-related meltdown on the set of Harold Lloyd’s “Movie Crazy,” Clyde Bruckman signed a short-term contract with Mack Sennett: one short film, with a shooting schedule not to exceed six days, and the option to hire him for two additional films at $1,000 per week. He was back in the Fun Factory, which had hardly changed since he’d last worked there in 1925. It was there he’d meet his last great collaborator, W. C. Fields. For Clyde, no one could have been more professionally congenial or personally ruinous.

Clyde’s newest partner occupied a wholly unique place in motion picture history; Roger Ebert aptly called him “the most improbable star in the first century of movies.” He played one character on screen and in life: a misanthropic drunk, trying hard to maintain a certain nineteenth-century dignity while under constant assault from the world around him.

Fields was on roughly his fourth career by the time Clyde worked with him. Born in Philadelphia in 1880, he’d begun in vaudeville as a juggler, making his way to New York by absconding with the receipts from a phony benefit show he’d put on, with advertising funded on what he’d later describe as “the pay-if-you-can-catch-us plan.” In New York, he’d risen through the minstrel shows and burlesques, touring with a number of companies before joining the Ziegfeld Follies in 1915. The Follies landed him “Pool Sharks,” his first short film, that same year. Having begun his career as a genuine con artist, he became a Broadway star by playing one: a patent medicine salesman in 1923’s “Poppy,” which Robert Woolsey would borrow liberally from years later in Clyde’s disastrous RKO film “Spring Tonic.” “Sally of the Sawdust,” D. W. Griffith’s silent adaptation of “Poppy,” was Fields’s entry into feature films. Coming from the stage, he’d made a smoother transition into talkies than many, and arranged a lucrative contract in 1932 to make short films for Mack Sennett. In November he’d finished the first of these, “The Dentist”—an excellent film, despite being exceptionally violent and misanthropic even for W. C. Fields. Sennett picked up the option on Field’s contract at the same time as Clyde’s and, probably thinking they’d be comedically simpatico, paired them together.

But by 1932, the two men also shared an increasingly all-consuming hobby. Fields had rarely touched a drink in his juggling days, but while touring with the Follies he’d picked up the habit as a way to fuel dressing room socialization, and by the 1930s, he was drinking heavily enough to make Buster Keaton look like a piker. Prohibition made the subject a little publicly touchy, but it didn’t really slow him down. Drinking was part of Fields’s persona, expected of him, and he played the role to the hilt. Biographer James Curtis points to this 1935 interview, after alcohol was legal again:

“I’m an advocate of moderation. For example, I never drink before breakfast. During the morning, I have 15 or 20 highballs. Then comes lunch. But I don’t eat lunch. Bad for the waistline. I drink it instead—oh, say, a gallon of cocktails. In the afternoon, which is longer than the morning, I have possibly 30 or 40 highballs. With dinner, I have ten or twelve bottles of wine or something to drink. In the evening, I like a case of sherry or maybe 50 to 60 highballs.”

Even the comic version is a little sick-making, but the facts, according to Norman McLeod, who directed him in 1934’s “It’s A Gift,” were positively unimaginable:

“After breakfast he downed a solid glass of bourbon with one-half inch of water in it. He said he didn’t want to discolor the bourbon. He had four or five of these until noon. He drank on the set. He was one of the few actors I knew of who was allowed to drink on the set. Then he had lunch. After lunch—he always ate big meals—he began imbibing again at 2:30. He would have four or five more bourbons until 5 p.m. At 5 p.m. he started on martinis. He’d have five or six martinis—he made a very good martini—before dinner. He was never drunk unless he consumed liquor after dinner. If he did, he went back to bourbon.”

This was not a man anyone with a drinking problem would be well advised to have as a coworker. But Clyde was able to hold things together over the five days of shooting around Thanksgiving of 1932. It helped that they were making a film that would not only withstand a certain amount of incompetence, but positively reward it.

The work at hand was an adaptation of “The Stolen Bonds,” a sketch Fields had performed on stage that sent up the shoddy writing, acting, and set construction of theatrical melodramas. For the film adaptation, retitled “The Fatal Glass of Beer,” Clyde and W. C. Fields made things even shoddier, adding an interminable parody of a temperance song and a terribly executed rear-projection sequence. The resulting film had what William K. Everson described as “a reckless lack of finesse” that was, for once, exactly the right approach. The sets are unimaginably cheap, Fields’s singing is punishingly awful, there’s barely any story, a group of Indians in full headdresses appear for reasons that are never explained, and the single funniest joke is about Fields eating his dog. The standout sequence from a filmmaking point-of-view has Fields announce that he is going to “milk the elk,” before going outside and attempting conversation with rear-projected stock footage of stampeding animals, which is: (1) out of focus, (2) lit completely differently than he is, (3) shot from the wrong angle, (4) at a completely different scale, and (5) edited with abrupt, unexplained cuts. It’s an absolute garbage fire of a movie, popping and fizzing with contempt for its audience, its subject, and the arts of theater, filmmaking, and presumably elk-milking. In other words, it’s a masterpiece. Fields, in a letter to Sennett, who saw and hated an early cut, summed up its appeal:

“You are probably one hundred percent right. ‘The Fatal Glass of Beer’ stinks. It’s lousy. But, I still think it’s good.”

Incredibly, the finished movie is less deliberately terrible than Fields wanted it to be; his plan was to have the camera stay on him for the entirety of his awful song about temperance. Sennett insisted on cutting away to shots of George Chandler as his son, illustrating the perils of alcohol as Fields sang about them. In some accounts, these were reshoots Sennett made Clyde make after viewing the original version, but the cutaway scenes appear in the shooting script from November 17, so it seems likely this was more of an editing dispute.

Some critics seemed to get the joke when the film was released: Film Daily called it a “Top-Notch Comedy,” although the reviewer may have been thinking of a different film, since the review also praises the “clever process work” of the elk-milking section. Audiences, in contrast, overwhelmingly agreed with Variety: “No real laffs and hardly a snicker.” Motion Picture Herald’s “What the Picture Did for Me” feature was exceptionally harsh. One theater owner reported “Two reels of film time and 18 minutes of time wasted,” and another liked it even less: “This is the worst comedy we have played from any company this season. No story, no acting and as a whole has nothing.” Like the ostensibly negative four-word review of “The Dentist” in the same issue (“Inexplicable. Rank. Uncalled for.”), complaining about the film’s lack of story, wasted time, or bad acting seems like a case of missing the forest for the horribly photographed trees. But as with “The General,” albeit for very different reasons, it would take years for audiences to appreciate “The Fatal Glass of Beer.”

More than eleven years earlier, in the summer of 1921, Clyde had worked on his first masterpiece, “The Playhouse.” It had been a carefully planned and executed clockwork toy, all elaborate special effects and precise timing: virtuoso work. With “The Fatal Glass of Beer,” he made his last masterpiece, a shambling wreck of a film, bursting at the seams with bad ideas, badly executed. It’s the cinematic equivalent of being cornered at a bar by a drunk whose manic, conspiratorial monologue somehow manages to be fascinating and hilarious. It sometimes does happen, but much less often than heavy drinkers come to believe. The hangovers are vicious.