Q. You wrote in your review of “Titanic,” “At one point Rose gives Lovejoy the finger; did young ladies do that in 1912?” This very question came up during an American Dialect Society’s online discussion of anachronisms in “Amistad” (where characters say “hello” despite the fact that the word was not used until the invention of the telephone). Apparently, the gesture has been used at least since the last century (there are photographs of 19C people giving the finger), although I’d say it’s unlikely that a young lady would have done so in 1912. (Alan Baragona, Staunton, Va.)

A. Now I have another challenge for the anachronism-hunters at the American Dialect Society. It may be a little off their specialty, but ask them to do their best. In “The Wings of the Dove,” a film based on a Henry James novel, two of the characters make love outdoors while braced up against a pillar in Venice. The novel is set earlier, but the film moves the action up to about 1910. In what year, according to the society’s best thinking, did young ladies of the sort Henry James writes about begin to participate in such practices?

Q. “Titanic” expects us to sit for 3 hours and 14 minutes without a restroom break. How would fans like to attend an NFL game and be told there is no half-time? You’re free to use the facilities, but you might miss a touchdown. Plus the theaters encourage you to buy their 64-ounce soft drinks. If you have bad luck you might be taking care of business when the ship hits the iceberg. (Art Yollin, Las Vegas, Nev.)

A. Not such bad luck compared to the people who were on the ship when it hit the iceberg.

Q. In “An American Werewolf In Paris” a young man leaps off the Eiffel Tower in pursuit of the fetching Julie Delpy (who jumped from the same point moments before). During the couple’s free fall, the young man overtakes Ms. Delpy and grabs her before she smacks the pavement. Duh? Isn’t this another case of film people snoozing through a high school physics class? I thought that all objects fall to Earth at a constant rate (assuming that gravity is the dominant force) regardless of their weight. And I don’t think that Ms. Delpy’s clothing would offer enough resistance to allow the young man to catch up to her. I know that movies are something like dreams and that the laws of physics do not apply to the dream world. Maybe if I can provide the suspension of disbelief for werewolves I can also put aside Newton’s Mechanical Universe. (James B. Stevens, Lisle, Ill.)

A. Close study of the Eiffel Tower reveals that it slopes out from a narrow top to a very broad base, so that even if Tom Everett Scott could have grabbed Delpy in midair, they would both have slammed into the girders of the tower’s sides, and continued on down to the ground doing a passable imitation of carrots being diced in a Veg-a-Matic.

Q. Over Christmas, I got caught into watching “Double Team,” the Dennis Rodman-Van Damme thriller, on video. Remember those WWII films where a bit player was always falling on a grenade to save the others hiding in the shell crater? He’s killed (bloodlessly–not hamburger) and nobody else is scratched. Well, in “Double Team” someone throws a grenade into a swimming pool. I’m expecting a woomp and some bubbles. What I get is a pool full of rocket fuel–a sheet of flame 30 feet high! Where the hell does that come from? Who fills their pool with gasoline? (Don Howard, San Jose)

A. Hey, just as long as Rodman keeps rebounding, I don’t care what he does off the court.

Q. I’m certain that you’re proud of your independence as a critic. But generally, are movie critics (mildly) pressured to “opine in line” with the public’s thinking? For example, if they kept blasting films that eventually grossed over $100 million, would they get fired? (Greg Brown, Chicago, Ill.)

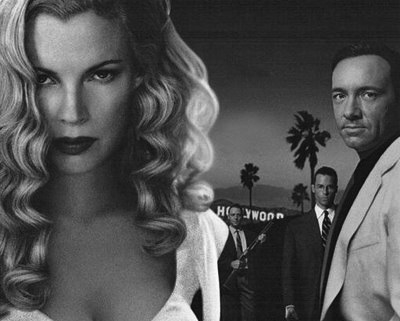

A. Depends on the outlet. Some publications and broadcast outlets hire critics who are specifically intended to reflect the views of their readers or viewers. These critics remind me of ventriloquists: They’re dummies sitting on the knee of the public. They’re of no use to you because their mission is to tell you what you already know. Wise editors will find critics who have a personal point of view and defend it interestingly, regardless of a film’s commercial prospects. Here’s a recent example involving “Titanic.” Gene Shalit’s editors on NBC’s Today show would probably have liked him to jump on the bandwagon, but he regretfully declined, reporting that he found the film a disappointment. Janet Maslin’s editors at The New York Times, who appeal to more elite demographics, would probably have preferred her to moderate her enthusiasm for such a middlebrow blockbuster, but she picked “Titanic” as the best film of the year, instead of going with such safer choices as “L. A. Confidential” or “Sweet Hereafter.” That took nerve. In both cases, editors got the benefit of their critics’ honest personal feelings.

Q. According to someone on our local talk radio station, Albert Broccoli the late producer of the James Bond movies is the son of Broccoli the biologist who developed the plant in the 1920’s (as a combination of cauliflower and Brussels sprouts) and had it named after him. Do you know if there’s any truth to this? (Mark Reichert, St. Louis, Mo)

A. Quite true. And the connection led to an unfortunate on-air goof when Albert Broccoli died. NBC-TV News in Chicago announced his death while, over the anchor’s shoulder, there appeared not Broccoli’s head but a head of broccoli. Something to do with a video librarian not quite understanding a request.