Netflix’s disjointed “The Monster of Florence” follows several suspects in the most notorious series of murders in the history of Italy. The titular villain murdered at least 16 people from the late-‘60s to the mid-‘80s, choosing couples that had pulled off for an intimate moment in the Italian hillside. After shooting and stabbing these young couples, he would often then mutilate his victims, cutting off genitals of the female ones. Remaining unsolved to this day, his identity has become something of a crime fiction legend, with Bryan Fuller’s “Hannibal” even suggesting that Hannibal Lecter might be the Monster and a recent theory gaining true crime prominence that the Monster and the Zodiac Killer could be one and the same. (I want to watch that bananas idea in a Netflix mini-series.)

There are as many theories to the Monster’s identity as there are victims. But Stefano Sollima’s 4-part Netflix mini-series follows the clues down what has been dubbed the Sardinian Trail, a multi-year investigation that essentially tried to discern the dynamic around the first killings, presuming that would then pull the threads for the rest. Needless to say, it did not, and no one went to jail for the bulk of the crimes to this day.

A “Zodiac”-esque approach to this winding case might have worked, in that every time the investigators thought they had the right suspect, something would upend their latest theory and send them in another direction. In the ‘80s, Italian authorities would arrest a likely suspect, only for the Monster to kill another pair of lovebirds while that person was in custody. It had to have been a spiraling world of frustration, a perfect fit for a procedural about the failed investigations that allowed justice to remain unfulfilled to this day. However, Sollima isn’t interested enough in the actual act of investigation, cutting back to the officers in charge of the case only really as bookends to four case studies of potential suspects, and largely how they tie into what is considered (but might actually not be) the first Monster murder.

In 1974, teenagers Pasquale Gentilcore and Stefania Pettini were shot and stabbed, her body mutilated after she was dead. Seven years later, after the Monster struck again, the authorities performed ballistics on the Gentilcore-Pettini bullet casings and discovered they were the same as the gun used to kill Antonio Lo Biano and Barbara Locci in 1968, a crime for which Locci’s husband Stefano Mele had been convicted. So he has to be the Monster, right? Well, he was in prison when Gentilcore & Pettini were shot. So either someone else used his gun or he was never the shooter in the first place.

Sollima uses each hour of his series to profile a different Sardinian suspect, starting with Mele; moving to one of Locci’s lovers named Francesco Vinci; getting to the arrest of Mele’s monstrous brother Giovanni Mele, under the theory that Stefano was covering for him; ending with the creepy Salvatore Vinci, another one of Locci’s lovers who the show profiles as a true sociopath. All of these men are presented as monsters, almost as if the show is suggesting that it doesn’t really matter who actually pulled the trigger or thrust the knife; it could be any of these guys, all of whom mistreated Barbara Locci in vile, misogynistic, violent ways.

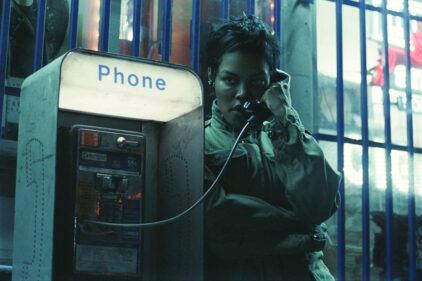

Turning an unsolved case into a commentary on sexual violence is an ambitious idea but it’s half-heartedly executed, in large part because we don’t really get to know Barbara Locci outside of seeing her abused and violated by so many people in her life. “The Monster of Florence” suffers greatly by not really having a protagonist. It could have been an investigator. It could have been Mele himself as he connects all of these suspects. It could have, and probably should have been Locci, the woman who was used for sexual pleasure and then murdered for her proclivities. It could have even been Mele’s son Natalino, the only living witness to a Monster murder. Maybe. History even allows the possibility that the ballistics connecting the Locci murder to the others is wrong, or that the gun got into someone else’s hands. No one knows. And “The Monster of Florence” even ends with the suggestion of a fifth suspect, Pietro Pacciani, the one whose trial in the ‘90s convinced Thomas Harris to set Hannibal in one of the most beautiful cities in the world.

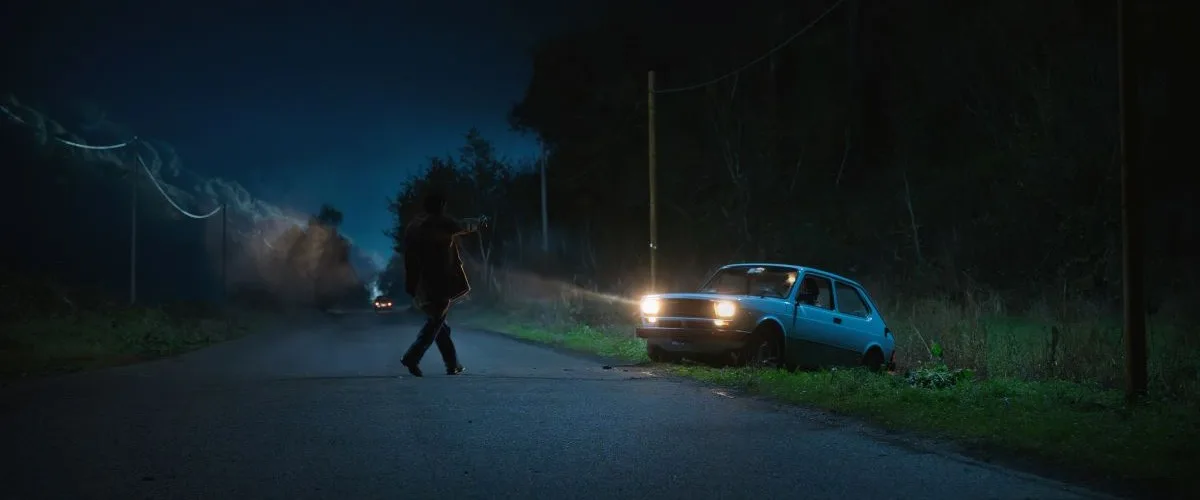

Ultimately, “The Monster of Florence” is so unfocused that it comes off hollow. Yes, it’s very difficult to make a succinct piece of art about an unknown maniac, which is why projects like From Hell and “Zodiac” use the crimes to say something else (usually about the people who become obsessed with them). Sollima can’t figure out what he’s trying to say or do with “The Monster of Florence,” outside of reminding us how dangerous even the most peaceful looking Italian hillsides and quaint villages can be. They could all hide a monster.

Whole series screened for review. On Netflix on October 22.