“Emergent City” is an old-school documentary that tells a story by presenting and arranging information and expecting you to meet it halfway rather than having everything spoon-fed to you. It’s about the political battle over Industry City, a manufacturing area located on the Brooklyn waterfront near Sunset Park, the neighborhood just north of Bay Ridge, where Tony Manero lived in “Saturday Night Fever.”

Sunset Park is a middle-class, demographically mixed area, heavy on Mexican Americans who’ve been putting down roots there for decades, as well as members of other demographic groups who moved there to escape rising rents in Manhattan and increasingly pricey parts of Brooklyn. Industry City is notable for still having a manufacturing base that offers native New Yorkers and immigrants union jobs with decent pay, in a city where (as in so many other urban centers) manufacturing has mostly been outsourced overseas, to factories that pay workers as little as they can get away with.

Industry City is geographically unusual for being all one chunk of property, comprising 35 acres. When Industry City was purchased by a consortium of five real estate companies—led by Jamestown Properties, the gigantic company that bought Chelsea Market in Manhattan and then sold it to Google for billions of dollars—there were immediate fears in the neighborhood that it was going to be remade as, basically, a glorified mall and luxury apartment bloc, jacking up property values and pushing out the same people who’d found a little paradise in one of the United States’ most expensive cities.

Directed by Kelly Anderson and Jay Arthur Sterrenberg, “Emergent City” is an excellent nonfiction film, and instantly relatable. If you’ve watched a beloved and still-affordable big city neighborhood with a unique character and history get turned into a yuppified mall full of restaurants and bars with cliche exposed-brick walls and twenty-dollar cocktails, and apartments and condos that sit half-empty for years because most of them were purchased as investments rather than places for humans to live in, you’ll recognize what has already happened when the story begins—and dread what feels like a preordained outcome.

The main narrative line concerns rezoning. When the story begins, Industry City is zoned for manufacturing. Jamestown wants it rezoned for mixed use so they can rent out the spaces to Manhattan companies looking to relocate, most of them unconnected to manufacturing, as well as real estate developers who want to build the equivalent of high-end shopping malls (watch how a representative of the company bristles when the word “mall” is used) and restaurants where a burger and fries costs more than you’d pay for a pair of shoes on Temu. The predominantly Latino locals are sharp and engaged and know what’s going to happen if they don’t band together with local white millennial and Gen Z leftists to pump the brakes on the process.

Luckily for them, rezoning has to pass through multiple levels of approval—community boards, city council, the mayor—and hold public hearings where citizens can raise questions, express concerns and make demands. Among the latter is a simple plea: if you’re going to totally change the character of an existing neighborhood and fill it with new people, can you at least make sure that the folks who have always lived there, and whose sweat equity made it commercially viable, can still have good jobs and affordable housing.

Unluckily, though, the process seems as if it’s going to follow the same arc that you see playing out in other cities: the major real estate redevelopment, whether it’s for a mall, an apartment complex, a stadium or something even bigger, is close to a fait accompli, with many local politicians already sitting in the developers’ pockets, and the more honorable ones walking a tightrope between constituents who know that local citizens tend to get screwed by these deals, and others who have bought into the notion that it’s a good thing because it will “create jobs.”

Create jobs for whom, though? And what kind? And what will be the pay? Those are urgently important questions. The developers tap-dance rather than answer it fully and honestly. They won’t say how much rezoning the area will increase its value and make it more flippable (see the Google sale, higher up in this review) at the expense of the local community. Nor will they allow themselves to be held to account on guaranteeing a certain percentage of affordable housing, and jobs comparable in pay and benefits to the manufacturing jobs that would be lost. There are many punchable faces on the corporate side. The most punchable of all belongs to the lawyer who tells community representatives, including a city councilman, that the real estate consortium isn’t going to promise that they won’t do certain things because they want to keep all their options open. Well, then—what’s the point of even sitting across a table, negotiating?

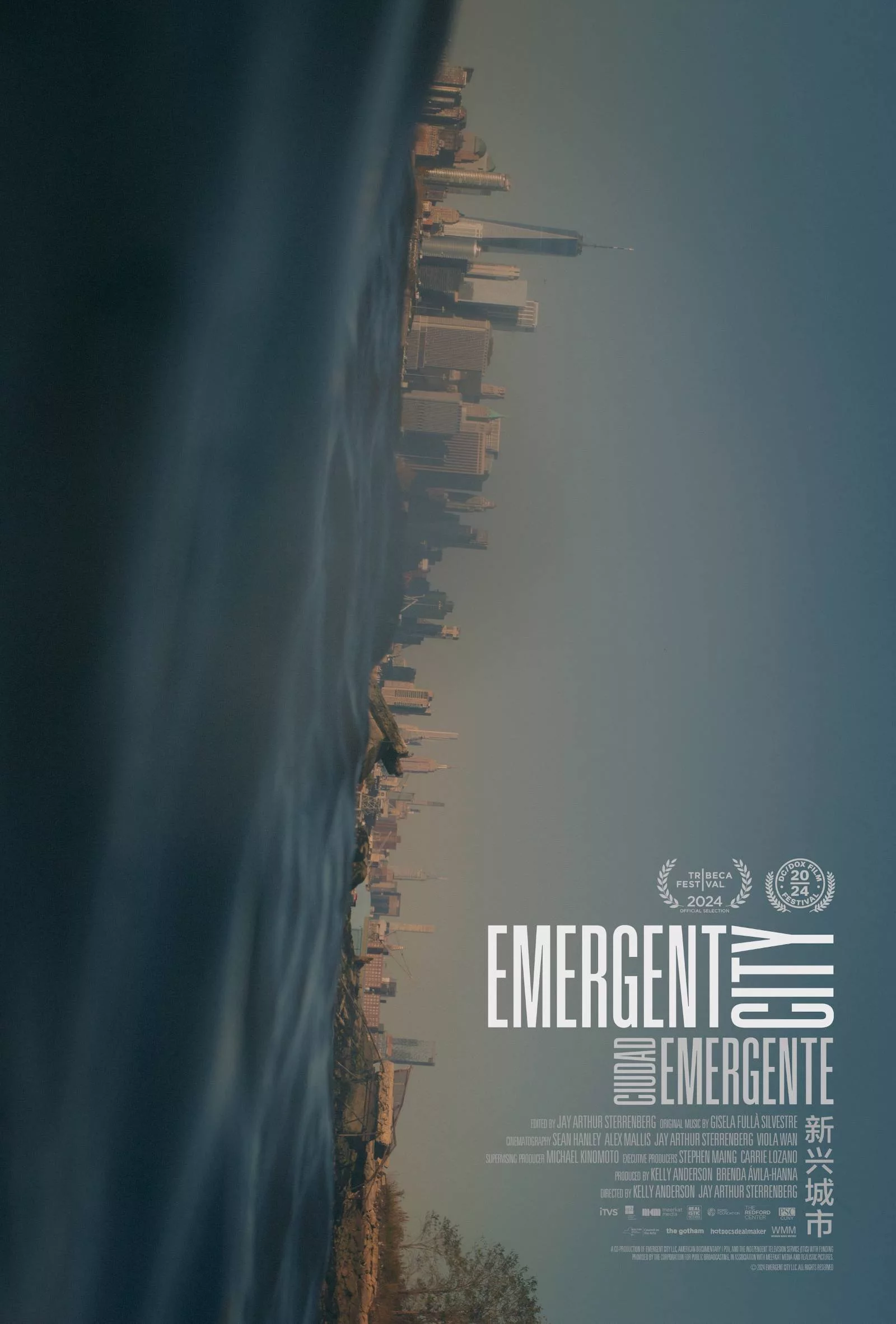

The filmmakers seem to have taken inspiration from the films of the great Frederick Wiseman (“Jackson Heights,” “Ex Libris”), whose movies about communities and institutions require a degree of intellectual participation that most viewers aren’t willing to give. This is a much shorter movie than Wiseman’s recent usuals, which tend to run three or four hours—it packs a lot into 97 minutes—and Anderson and Sterrenberg help situate us within the story with subtle graphics that identify the corporate and community representatives and local citizens who have a stake in the outcome because their families have lived in Sunset Park for years or decades and don’t make enough money to just pick up and relocate. (This is also a rare documentary that uses drone cameras for something other than “production value”: the aerial views of Brooklyn superimpose the names of neighborhoods and streets, situating you geographically.)

The tone of the film is gently instructive. The distress of neighborhood people naturally puts the viewer on their side, and the ingrained smugness of the real estate company reps and their lawyer doesn’t balance out the films’ sympathies; but despite all that, “Emergent City” mostly follows the tenets of proper journalism, presenting all the sides and issues and laying out the narrative in a comprehensive but clear manner. Once you get intellectually and emotionally invested, though, it becomes nerve-wracking, because it’s clear that the neighborhood reps are idealistic but disorganized and often at odds with one another; and because you know people with power and money tend to steamroll everybody else.