Today, fifteen years after I first saw it, I believe “Hoop Dreams” is the great American documentary. No other documentary has ever touched me more deeply. It was relevant then, and today, as inner city neighborhoods sink deeper into the despair of children murdering children, it is more relevant. It tells the stories of two 14-year-olds, Arthur Agee and William Gates, how they dreamed of stardom in the NBA, and how basketball changed their lives. Basketball, and this film.

Today, fifteen years after I first saw it, I believe “Hoop Dreams” is the great American documentary. No other documentary has ever touched me more deeply. It was relevant then, and today, as inner city neighborhoods sink deeper into the despair of children murdering children, it is more relevant. It tells the stories of two 14-year-olds, Arthur Agee and William Gates, how they dreamed of stardom in the NBA, and how basketball changed their lives. Basketball, and this film.

Photo copyright by Roka Walsh. Used with permission

“Hoop Dreams” observed its 15th anniversary Wednesday night at the Gene Siskel Film Center. Agee and Gates were both there. Gates, now a minister, observed that in one period of time he buried 20 victims of gang violence, 16 of them under 16. Agee said when he looks at his friends in the film today, “ten of them are no longer with us.” Yet there they sat, men of around 40 now, articulate, thoughtful, and spoke about how their lives began to change on a Chicago playground 22 years ago when a movie camera showed up.

“We started out to make a little 30-minute documentary about a kid who had basketball dreams,” Steve James, the director of the film, said Wednesday night. This was at a benefit for Kartemquin Films, the 40-year-old Chicago documentary group that produced the film.

“A talent scout for suburban high schools led us to Arthur. Through that we met William. We kept right on filming. We ended up five years later with 250 hours of film. We edited it down to just under three hours. We only had enough money to shoot a half-hour film. We never did get much more, but we kept on filming.

How could they stop filming? “Hoop Dreams” unfolds as a human drama so powerful it seems crafted from fiction, and arrives at a climax more exciting than any other sports film. And it’s about so much more than that. It’s about two young men who we follow from grade school to college. About the poor neighborhoods they grow up in, and about the wider society they hope to enter. About their families. About life and death. About the elusive dream of stardom in professional sports. And about the indomitable human spirit.

Arthur Agee after a big Marshall win in the state high school finals

”Do you all wonder sometimes how I am living?” Arthur’s mother, Sheila, asks the filmmakers at one point, turning directly to the camera. ”How my children survive, and how they’re living? It’s enough to really make people want to go out there and just lash out and hurt somebody.” Yes, we’ve wondered. Her family is living on $268 a month in public aid; when Arthur turned 18, his $100 payment was cut off, although he was still in high school. Their gas and electricity had been turned off in the winter. The family was using a camp lantern for light.

During the course of the film Sheila’s husband leaves and gets into trouble, she suffers chronic back pain, she loses a job and goes on welfare, Arthur can’t meet the tuition and is dropped by St. Joseph’s, the suburban high school that recruited him. After the school actually refuses him a copy of his transcript for not paying bills his family wouldn’t have if St. Joseph’s hadn’t foraged in his neighborhood for a winning team, he transfers to the public Marshall High School, and leads them to the state finals. Take that, St.Joe’s.

Then, in the film’s most astonishing revelation, we see Sheila graduating as a nurse’s assistant, with the top grades in her class. We didn’t even know she was taking classes. Gene Siskel told me, “Arthur and William are applauded by hundreds or thousands of sports fans. When you see that nurses’ graduation day ceremony, most of the folding chairs are empty. She’s the one who deserves the standing ovation.”

William Gates playing for Marquette

Gene and I saw the film early. We were approached by a friend of ours, the Chicago publicist John Iltis, who didn’t ask us to see a screening, he told us this was a film we had to see. We believed him. We were the only people at the first screening outside Kartemquin. Iltis rented the original auditorium of the Film Center of the School of the Art Institute — which has become, fittingly, the new Siskel Center. When the movie was over we remained in our seats for a minute or two before speaking. Neither one of us had ever seen anything like it. It didn’t have distribution. It had been accepted at Sundance. We decided to break the rules and review it before Sundance, hoping that more people would see it. It won the Audience Award,

The way seemed clear for an Academy Award as best documentary. Then a shameful thing happened. It wasn’t even nominated by the Academy’s documentary committee. We learned, through very reliable sources, that the members of the committee had a system. They carried little flashlights. When one gave up on a film, he waved a light on the screen. When a majority of flashlights had voted, the film was switched off. “Hoop Dreams” was stopped after 15 minutes.

There was such outrage that the Academy, under attack led by the great Oscar-winning documentarian Barbara Kopple, rewrote its rules for the documentary selection process. “Hoop Dreams” wasn’t nominated, but it changed the Academy rules, it is still widely seen, and the reforms are its lasting legacy. None of this was even mentioned at the tribute on Wednesday. Many people assume it did win the Oscar? Who remembers what the 1994 winner was? (It was “A Strong, Clear Vision,” a worthy winner in any other year, but still…)

Over the years I’m repeatedly asked, “Whatever happened to those to kids in ‘Hoop Dreams?’ ” People get invested in their lives. Gates and Agee reflected on the 22 years since they first saw Steve James and his Kartemquin collaborators Peter Gilbert and Frederick Marx, and the 15 years since the Sundance premiere. Today they’re university graduates with satisfying jobs (William a minister, Arthur running the Arthur Agee Role Model Foundation, funded by his line of Hoop Dreams sporting wear).

Arthur Agee playing for Arkansas State

When they were 14, things weren’t headed that way. “You see my father one time in the film,” William Gates said. “That’s probably how many times I saw him. Arthur had both parents at home, but his father fell into drug abuse and his mother kicked him out. He got clean and sober, and returned home. When Arthur was being courted with scholarship offers, his parents told him, “Do what you want to do.” His father said, “We’ll support you. If I have to steal paint to do it, I’ll do it.” William’s girl friend Catherine got pregnant. He was offered a scholarship to Marquette and felt he had it accept it, but his decision caused them troubled times — even though he made the list of Marquette’s all-time basketball letter winners.

Wednesday night, he introduced Catherine in the audience, “My wife of 17 years. She was determined to get a college degree, but we couldn’t both be in school at once. We made an agreement: I promised when I got mine, I would work to help put her through school. Today we have two college graduates in the house.”

We’d just seen clips from the film showing them at 14. “What did we know then about what we wanted?” Arthur asked. “I plan to study communications.” He was mimicking himself sounding serious at 14. “Yeah, communications. What is that? It’s easy, that’s what. All the athletes study it.”

“Hey, I have a degree in communications!” William said.

“Me too,” Arthur said. “Don’t mean I wanted to!”

“Hey, so do I!” said Steve James.

Gates and Agee said that as the filmmakers following them for five years, they became mentors and role models. They met each other’s families. Their ideas of possibilities were broadened. They lived in desperate neighborhoods. When they were both recruited on scholarship by St. Joseph’s High School in west suburban Westchester, they commuted there daily by public transportation. “I saw there was a line,” Arthur said. “Out there, I saw nice lawns. The homes were well-tended.”

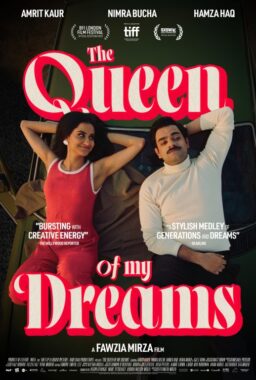

22 years after they met: William Gates, Arthur Agee, cinematographer Peter Gilbert and director Steve James. Acting as co-producers were Gilbert, James and Frederick Marx, not present, who was also co-writer. (Photo by Ruthie Hansen)

“I’m the same person inside as that confident 14-year-old,” William said. “I was so gifted. Basketball came naturally to me. It was like walking. But I’ve had a better life than if I’d gone into the NBA. As a pastor, I can talk to the young people. They see the film, and know I came from where they’re coming from. If I’d been an NBA star, they’d need an appointment to see me.”

After the panel discussion, the speaker was Alex Kotlowitz, author of There Are No Children Here: The Story of Two Boys Growing Up in The Other America, the heartbreaking best-seller about of two boys growing up on Chicago’s West Side. He is currently writing and producing on “The Interrupters,” a new doc being directed by Steve James for Kartemquin, about former gang members and convicts. They’ve formed a Chicago organization that tries to anticipate gang violence and personally intervene. Speaking after a clip from the work in progress, Kotlowitz quoted Nelson Algren: “American literature is a woman standing in a courtroom and asking, Isn’t anyone on my side?“

One noble purpose of documentaries, he said, is to be on the side of the kinds of people asking that question. Then he quoted words by Studs Terkel that summarized the spirist of William Gates, Arthur Agee, the makers of “Hoop Dreams” and the film itself: “I live in a community, and if the community isn’t in good shape, neither am I.”

On Monday, 11/9/2009, the IFC Center in New York will have an anniversary screening and a Q&A with Peter Gilbert.

Siskel & Ebert’s review of “Hoop Dreams.” Gene and I both put it #1 on our year’s best 10. I selected it as the best film of the 1990s. Gene died on Feb. 20, 1999, but if there’s one thing I’m sure of…

“Hoop Dreams,” the complete film online.

“Hoop Dreams,” streaming instantly on Netflix.

“Hoop Dreams: Serious Game,” an essay on the Criterion site by John Edgar Wideman.

My review of “Hoop Dreams” in the Great Movies Collection.

Whatever happened to that coach in “Hoop Dreams?”

Get the <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/widget/roger-ebert-ebertchicago-on-twitter”>Roger Ebert (ebertchicago) on Twitter</a> widget and many other <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/”>great free widgets</a> at <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com”>Widgetbox</a>! Not seeing a widget? (<a href=”http://docs.widgetbox.com/using-widgets/installing-widgets/why-cant-i-see-my-widget/”>More info</a>)