I think I may have just seen the 2010 Oscar winner for best foreign film. Whether it will win the Palme d’Or here at Cannes is another matter. It may be too much of a movie movie. It’s named “A l’origine,” by Xavier Giannoli, and is one of several titles I want to discuss in a little festival catch-up. Based on an incredible true story, it involves an insignificant thief, just released from prison, who becomes involved in an impromptu con game that results in the actual construction of a stretch of highway. At the beginning he has no plans to build a highway. He simply sees a way to swindle a contractor out of 15,000 euros. He is sad, defeated, unwanted, apart from his wife and child, sleeping on a pal’s sofa. What happens is not caused by him nor desired by him. It simply happens to him.

I think I may have just seen the 2010 Oscar winner for best foreign film. Whether it will win the Palme d’Or here at Cannes is another matter. It may be too much of a movie movie. It’s named “A l’origine,” by Xavier Giannoli, and is one of several titles I want to discuss in a little festival catch-up. Based on an incredible true story, it involves an insignificant thief, just released from prison, who becomes involved in an impromptu con game that results in the actual construction of a stretch of highway. At the beginning he has no plans to build a highway. He simply sees a way to swindle a contractor out of 15,000 euros. He is sad, defeated, unwanted, apart from his wife and child, sleeping on a pal’s sofa. What happens is not caused by him nor desired by him. It simply happens to him.

This is one of those movies that catches you in its spell. It’s a hell of a story. There’s a difference between caring what happens in a movie, and merely waiting to see what will happen. The hero, who calls himself Phillip, ends by bringing about an enterprise involving millions of euros, hundreds of workers and tons of massive earth-moving machinery, falling in love with the lady mayor, and becoming a good man, all without ever saying very much. I was reminded of Chance the Gardener In “Being There.” Phillip is shy, socially unskilled, inarticulate, apparently the opposite of a con man. To repeat: There is a true story involved here. Some facts are offered at the end. The highway, which which the workers essentially built on their own, with the con man as “management,” was completed on time, under budget and up to code.

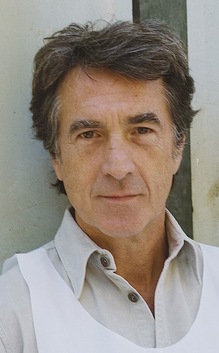

François Cluzet: A man with a nice face (Click all art to enlarge)

François Cluzet: A man with a nice face (Click all art to enlarge)

The character is played by the veteran French star François Cluzet, who played the lead in last year’s “Tell No One,” the top-grossing foreign film in the North American market. That was the superb thriller about the dead wife who wasn’t dead. A handsome, undernourished-looking man in his 50s, with a pleasantly lined face, looking something like Dustin Hoffman, Cluzet co-stars with Emmanuelle Devos, who you will recognize from a dozen French films. Gerald Depardieu has an important, if over-billed, supporting role. Cluzet’s performance is the key. He never says much, allows people to assume things he has not claimed, allows them in a sense to con themselves. He’s more fascinating than the impostor in Spielberg’s “Catch Me If you Can.”

It has been a very good year for French films at Cannes. One of the most-loved has been Les Herbes Folles, (“The Wild Grass”) by Alain Resnais, whose “Last Year at Marienbad” (1961) was one of the founding films of the New Wave. Now 86, looking fit and youthful on the red carpet, he has made one of those films perhaps only conceivable in old age. It is about an unlikely and fateful chain of events that to a young person might seem like coincidence, but to an old one illustrates the likelihood that most of what happens in our lives comes about by sheer accident. To realize this is to become more philosophical; the best-laid plans of mice and men are irrelevant to the cosmos.

To explain how this could all possibly happens would be not wild (folles) but a folly (une folie). Here is how it begins: The heroine Josepha (Sabine Azéma) decides one day to buy a pair of shoes. That leads to her purse being snatched. That leads to Georges (Andre Dussollier) finding her wallet. That leads to everything else. Resnais uses an omniscient narrator, as he must, because only from an all-knowing point of view can the labyrinth of connections be seen. He films in a colorful, leisurely style; not taking even the most serious things too very seriously, because, after all, they need never have happened.

Alain Resnais and his star, Sabine Azéma

Alain Resnais and his star, Sabine Azéma

Le pere des mes enfants (“The Father of My Children“) belongs to the genre of the country house movie, French division. British country house movies are a mix of Jane Austen, Agatha Christie and Evelyn Waugh, with Wodehouse as the mixologist. French country house movies tend to tell bourgeois family stories, including children of all ages, and they tilt toward the pastoral. This film, the third by Mia Hansen-Løve, only 28 and is a rising star of French cinema, stars Louis-Do de Lencquesaing as a movie producer who is willing to take chances on serious auteurs and is currently deep in debt, not least because of his backing of a temperamental perfectionist not a million miles separated from Lars von Trier. The story is said to be inspired by the real-life producer Humbert Balsan, who made von Trier’s “Manderlay” (2005)

The producer is a nice man. Too nice. Too loving, too loyal, too driven. We begin by following him through desperate attempts to keep his company afloat, and then watch as his wife (Chiara Caselli) and children try to deal with the impossibilities he has created. Some of this happens in Paris, much of it happens in his country house, and the focus is not on film production but on family. I was reminded of two other recent French films: the current “Summer Hours,” about an old lady leaving a legacy for her family to deal with, and last year’s “A Christmas Tale,” with Catherine Deneuve as a mother less worried about her death than her children are.

Los Abrazos Rotos (“Broken Embraces“) is the much-awaited new Pedro Almodóvar collaboration with his recent muse, Penelope Cruz. It’s about an old man remembering a woman he loved. Lluis Homar (“Bad Education“) plays a director who went blind in an auto accident that killed his love (Cruz), who was his secretary, and who he met as a call girl. Now he works as a successful screenwriter, using touch-typing. One day he’s approached by an ambitious young filmmaker named Ray X (Ruben Ochandiano), who he suspects is the son of the evil millionaire he holds responsible for the woman’s death.

Man on the verge of a nervous breakdown

Man on the verge of a nervous breakdown

As always with Almodóvar, it isn’t nearly as simple as that. Using interlocking flashbacks, the film reconstructs what actually happened in a combination of overwrought Sirkian melodrama and Hitchcock. The music, indeed, pays homage to Bernard Hermann’s work, particularly his score for Hitchcock’s “Vertigo,” and the film’s romantic entanglements pay homage to Almodóvar’s own pansexual stories. Cruz is a life force, but Homar’s work is the film’s engine.

It must be a year for movies about old men remembering lost parents and lovers. One of the more unexpected successes here is “The Time That Remains,” a deadpan Palestinian comedy written by, directed, and starring Elia Suleiman. Read that again: a deadpan Palestinian comedy. And not especially political, although almost all stories set in Israel must be political to one degree or another.

The film, dedicated to the memory of Suleiman’s parents, shows his father as a firebrand gun-maker, gradually aging into an old guy who sits outside a cafe with his pals, smokes, smokes, smokes, and drinks coffee as if he has kidneys of steel. This family lives in a small but pleasant flat with a nice view of Nazareth; they’re part of a friendly community. The film consists of fairly self-contained vignettes of human nature, reminding me curiously of the Czech New Wave comedies. The character played by Suleiman, satire linked with autobiography, a solemn, silent figure with dark shadows under his eyes, is poker-faced and never speaks. He simply stands and regards all that happens for 60 years. I don’t know what that makes it sound like to you. I was surprised by how it grew on me. The karaoke scene is unreasonably funny.

Elia Suleiman: Not much to say

Elia Suleiman: Not much to say

“Irène,” by Alain Cavalier, 77, a frequent Cannes winner and nominee, is a personal, subjective, experimental meditation on the 1972 death of the actress and beauty pageant winner Irene Tunc. Unlike Cavalier’s conventional narrative films (“Thesese”), this one actually shows very few speaking actors. It is almost all done with his own first-person narration, and a hand-held camera that examines diaries and other relics of a life ended but not forgotten. More than half Cavalier’s own lifetime has passed since Irene died, and his old man’s attempts at amends are very touching. The film received an unfairly dismissive review from Variety.

One of the final Official selections, Gasper Noe’s “Enter the Void,” is a nearly unendurable in-depth investigation of a very shallow idea. The camera positions itself close behind the head of a callow youth, jug-eared and crew-cut, as he films with his video camera and then becomes the camera as the remainder of the film is seen from his POV. The hero, an orphaned American, lives with his sister in Tokyo, where she is a nude dancer and possibly a booker, and he is a druggie and possibly a dealer. If they don’t practice incest, you could have fooled me.

After he dies in a shooting at a nightclub named the Void, we live through subjective scenes intended as what he sees after death. They involve flashbacks, replays of what has already happened, and hovering above what’s happening now. In Noe’s view, the soul does survive the body, which for much of this time has been cremated. These scenes are spaced out with sound and light abstractions resembling 1960s underground films past their shelf life. If Noe’s camera plunges into a vortex once, it does so a hundred times: Into white holes, black holes, psychedelic kaleidoscopic holes, over and over and over again, representing the delightful diversity of the Void. The visuals might have been juicier if he had known abut fractals. The film includes obligatory genitals of both genders, and one of the voids the POV plunges into is the mess in a stainless steel pan after an abortion.

Looking for Eric, by the great British director Ken Loach, is a disappointment, his least interesting work. It involves a hapless man named Eric, from Manchester, whose life takes a turn for the better after the spirit of Eric Cantona, the great star footballer for Manchester United, materializes in his bedroom. Cantona plays himself, produced the film, and may have been involved in the financing, which could explain how it came to be made. What I can’t explain is why Loach choose to make it. Maybe after so many great films he simply wanted to relax with a genre comedy. It has charm and Loach’s fine eye, and the expected generic payoff.

But I had a problem I’m almost ashamed to admit. Loach has always made it a point to use actors employing working-class accents, reflecting the fact that accent is a class marker. I’ve always been able to understand them–it’s the music as much as the words, and then I start to hear the words. This time, his star Steve Evets uses an accent so thick many of the English themselves might not be able to understand it. Ironically, the Frenchman Eric Cantana is easier to understand.

¶

The streets of Cannes, a madhouse a week ago, have grown strangely quieter. The press screenings have empty seats. The daily festival newspapers have called it a wrap. Old friends who have been racing against time all week are now finally making plans to meet at dinner. There are a few films still to play, and some to be repeated. Then the jury will appear on stage in the Auditorium Lumière and reveal its awards, and there will be cheers and boos and a big party under an enormous tent for about 1,000 of the survivors. Sometimes I feel I have spent my whole life at Cannes, and the rest is just trips out of town.

¶

Now for something completely different. I was attending the first Cannes screening for “Le Père de mes Enfants.” Before the film began, Thierry Fremaux, director of the festival, appeared onstage and introduced Mia Hansen-Løve and her entire cast, and they walked down a side aside and ascended to the stage. Then they did something unexpected and rather beautiful. They didn’t line up in a row and face the audience. That’s what a movie cast always does. I’ve seen it dozens, maybe hundreds of times. You have, too. With perhaps an older actress holding hands with a little one. They file on, they file off.

What these actors did was make a statement with body language. They stood around. They behaved as if they were really there. They took possession. As if they were at a cocktail reception. None of them faced the audience while standing at attention. They relaxed. Some stood a little forward, others a little behind. Some looked offstage, or at a friend in the audience, or at each other. They spoke a little among themselves. They didn’t ignore the audience, nor were they very aware of it. They were relaxed and at all times graceful. Annie Liebowitz couldn’t have arranged them any better for a Vanity Fair cover. Whether this was planned I have no idea. I doubt it. It felt natural and instinctive. That’s all. I just thought I’d mention it.

What these actors did was make a statement with body language. They stood around. They behaved as if they were really there. They took possession. As if they were at a cocktail reception. None of them faced the audience while standing at attention. They relaxed. Some stood a little forward, others a little behind. Some looked offstage, or at a friend in the audience, or at each other. They spoke a little among themselves. They didn’t ignore the audience, nor were they very aware of it. They were relaxed and at all times graceful. Annie Liebowitz couldn’t have arranged them any better for a Vanity Fair cover. Whether this was planned I have no idea. I doubt it. It felt natural and instinctive. That’s all. I just thought I’d mention it.

¶

Hanging out in the lobby of the Hotel Splendid with Chaz and the celebrated cineaste Pierre Rissient. Supporting role by our assistant, Carol Iwata.

¶

How much longer until the movie starts? Virtual waiting during six minutes before a morning press screening. The money shot is at the end: Every Lumiere screening begins with the stairway climbing from the sea to the stars.

¶

Pierre holding court at his home away from home