“We are the guardians of all deeds since we arrived in this territory.” So states one of the self-described jihadists who, with his colleagues and some high-caliber weaponry, are presuming to rule a small village and its surrounding grazing land and waters near the place of the film’s title. A thoroughly remarkable and disquieting film from Mali’s Abderrahamane Sissako, “Timbuktu” is also a work of almost breathtaking visual beauty, but it manages to ravish the heart while dazzling the eye simultaneously, neither at the expense of the other. It’s a work of art that seems realized in an entirely organic way.

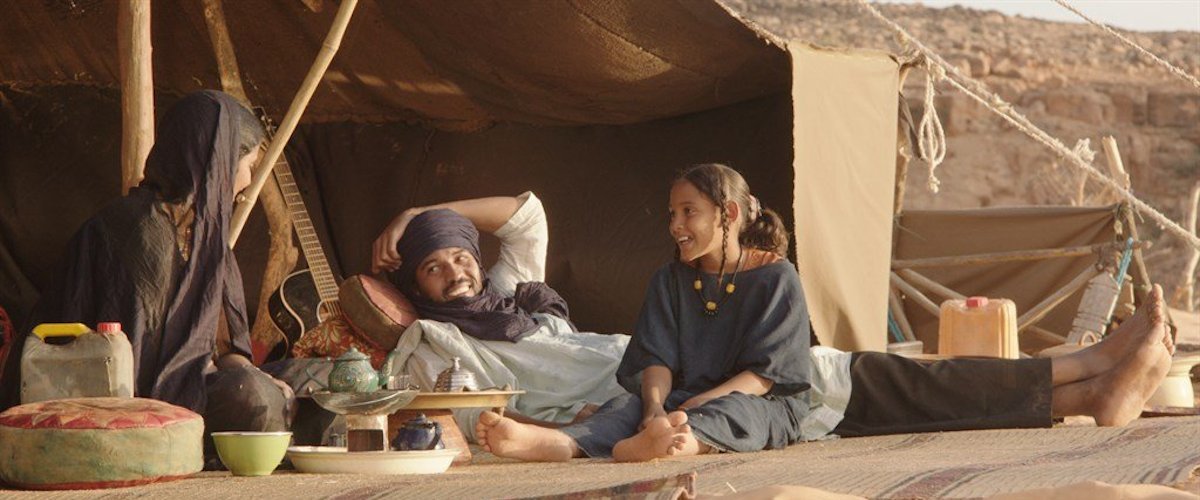

After a tense scene in which a group of men with automatic weapons chase a gazelle over sandy stretches, seeking to tire out the animal, Sissako’s movie quietly shifts to village life. Undercurrents of dread make themselves known as mere irritants at first. “Roll up your pants, it’s the new law,” a fellow with a gun says to a passing man. A woman selling fish is ordered to put on gloves, to conform to what the fellows with the guns say is Sharia law; she protests that she can’t handle fish with gloves on. A cleric takes exception to some men entering a mosque with their weapons. And so on. Outside the village, a cattleman of modest means, Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed), lives cheerfully with his wife and daughter. They seem nomadic, spending nights under tents, but the daughter has a cell phone; like almost everyone else in this sub-Saharan world, they seem suspended between the ancient and the post-modern. It’s a condition that brings about its own set of contradictions, contradictions the occupying jihadists abrade. Kidane’s wife, Satima (Toulou Kiki), has for some reason—perhaps her beauty—caught the intention of the chief of the self-described jihadists, the gentle-eyed Abdelkerim (Abel Jafri).

One feels that nothing good can come of all this, but the movie’s animating conflict winds up being something rather more altogether Old Testament, at least from the perspective of a Western viewer. After Kidane loses a beloved cow to the spear of a local fisherman, irritated that the beast has wandered into his nets, Kidane foolhardily puts a weapon on his person as he goes to seek justice. The worst happens (and its aftermath is depicted in an incredible long take shot from a considerable distance, a jaw-dropping piece of filmmaking), after which the ruling jihadists swoop in to police the situation, and subsequently advise Kidane to try to place his affairs in order, as he cannot escape the fate that, he and his captors agree, he cannot control. Abdelkerim sees in Kidane’s plight a chance to make a “good” impression on Satima, but he, too, will learn that there are some things beyond his ability to affect.

This main storyline is only given slightly more emphasis than the other threads this movie weaves into its tragic fabric. Some friends who are put to the lash for the crime of playing music. (And the music in the film, incidentally, is as beautiful as its imagery.) A young woman whose mother objects to a jihadist’s proposal of marriage that later becomes a demand. And so on. The really killing thing about all the conflict that tears this place and its people apart is how calm everyone is about it. Nobody raises his or her voices; nobody raises a hand in impulsive anger. Violence, when it occurs, is done in a very deliberate way. The jihadists need to conduct themselves “properly,” as this conveys their rectitude. But their stance only barely disguises their old-fashioned bullying. The treatment of women in particular is just misogyny with unconvincing window dressing. The jihadist who wants the young woman in marriage expects no argument; the girl is his right. And the fact that he asks for her politely, in the logic he lays out, only underscores his alleged right. It doesn’t matter anyway; if he is refused, he calmly states, “I’ll come again in a bad way.”

This small-scale totalitarianism that claims to be the way of Islam and is only justified via the barrel of a gun or the point of a lash is depicted by Sissako with pinpoint clarity. As is the hypocrisy, as in Abdelkerim’s decree forbidding tobacco, from which he “secretly” exempts himself. The scene in which his driver, who previously has registered some small objections to the way his boss does things, tells Abdelkerim that he needn’t hide his cigarette use from him, is both smile-inducing and terrifying, because the viewer isn’t sure exactly how much real viciousness Abdelkerim has within him, and how much that viciousness can be triggered by his vanity. Part of what makes “Timbuktu” such a striking film is the way Sissake insists on giving the jihadists full humanity even as he clearly and deeply deplores their actions. This feat of understanding and empathy is just one of the many things that this exceptional film executes exceptionally well.