“Three Days of the Condor” is a well-made thriller, tense and involving, and the scary thing, in these months after Watergate, is that it’s all too believable. Conspiracies involving murder by federal agencies used to be found in obscure publications of the far left. Now they’re glossy entertainments starring Robert Redford and Faye Dunaway. How soon we grow used to the most depressing possibilities about our government — and how soon, too, we commercialize on them. Hollywood stars used to play cowboys and generals. Now they’re wiretappers and assassins, or targets.

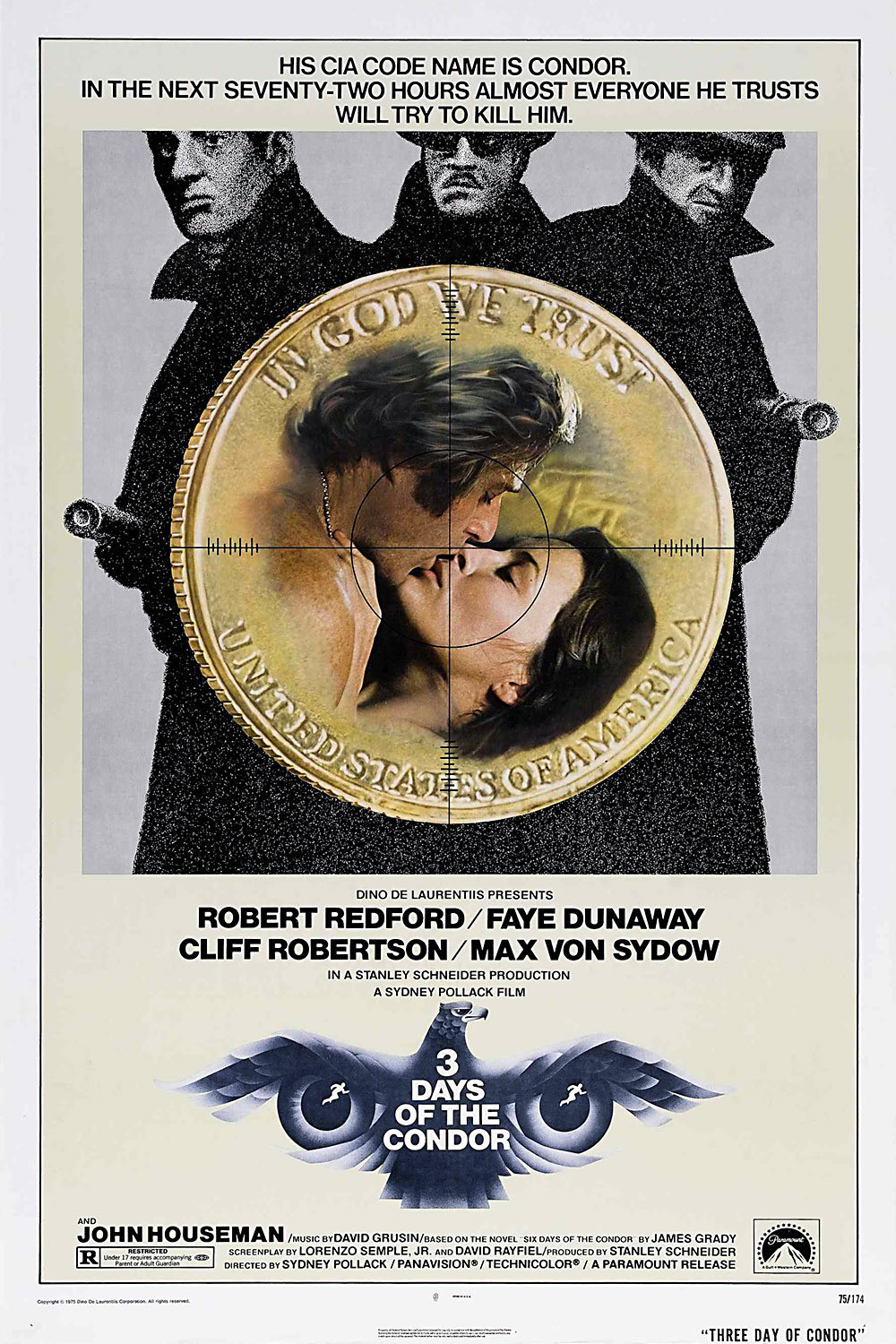

Redford is a target this time, and he makes a good one, all open-faced and trusting. He’s a reader for something called the American Literary Historical Society, and he looks like a graduate student, with his tweed coat, jeans and sneakers. The society is a CIA front. The movie doesn’t exactly make its activities transparently clear, but it seems to devour and computerize foreign books and magazines in a search for codes and messages.

Redford’s research has turned up a book translated into just three languages: Spanish, Dutch and Arabic. Why only those three? Well, by the time we figure out those are the languages of major oil-exporting areas, all of the workers at the society except Redford have been shot dead. He was, luckily, out to lunch. He calls up the CIA to ask them to bring him in from the cold (how quickly we learn the latest spy jargon!), and the Company sets up a rendezvous at which he’s nearly murdered. Here’s a man, if ever there was one, who has paranoia thrust upon him.

Redford brings a nice dogged seriousness to his role: He would very much like to stay alive, so he’s got to rethink all of his assumptions about the CIA. (“Why is it,” he reasonably asks a telephone contact, “that I have to identify myself to you, but you don’t have to identify yourself to me?”) The movie becomes the story of how he stays alive and unwittingly reveals a conspiracy within the agency.

He’s assisted by Faye Dunaway, playing a girl named Kathy who’s the very embodiment of pluck. He kidnaps her in order to use her apartment as a hideout, but something about him (perhaps his uncanny resemblance to Robert Redford) convinces her that he’s not paranoid — that, indeed, there really are people trying to kill him. She’s fairly neurotic herself, but she’s a good sort and she helps all she can. And she has three lines of dialog that brings the house down. They’re obscene and funny and poignant all at once, and Dunaway delivers them just marvelously.

The film’s director, Sydney Pollack, has worked with Redford three times before (they made the epic “Jeremiah Johnson” and the considerably less-than-epic “The Way We Were“). He does an interesting job of gradually revealing the net around his character. It’s made up of business like types, the most chilling thing about them, indeed, is their bloodlessness as they discuss death and other “contingency plans.”

One of them is a hired assassin, played with particular menace by Max von Sydow. One is the dispassionate bureaucrat (Cliff Robertson). And one (John Houseman) is a demented product of Cold War double-reverse strategy. The movie never pushes their various and labyrinthine conspiracies too far. We can believe that the CIA might behave in this way — and that it possibly has. The ending, when it comes and when it’s explained with such cruel logic by von Sydow, has the right ring. A very hollow one.