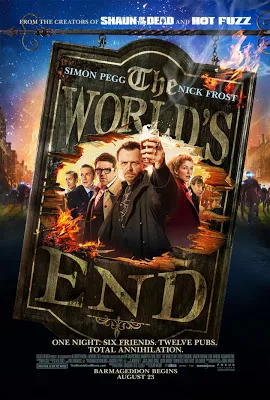

You might not expect a slapstick comedy about middle-aged pubcrawlers brawling with superhuman extraterrestrial invaders to have brains, heart and wisdom, but that’s “The World’s End,” a rare film that’s as much fun as you’ve heard.

Directed by Edgar Wright from a script by him and his regular leading man, Simon Pegg, the film is refreshingly intimate, despite the chasing and stalking and beheading and exploding and gallons of blue goop spraying all over everything. The special effects are special, but they always serve the story and characters. And even when Wright is paying homage to his filmmaking heroes (John Carpenter especially) or staging some of the most cleverly choreographed fights this side of an early ’90s Jackie Chan film, you never get the sense that it’s bored with itself when the characters are sitting around talking about their shared history over a pint. In fact, they often talk about their shared histories while they’re whaling on the invaders—and then they have a pint. Sometimes they have a pint during the fight. It’s that kind of movie.

Pegg’s character, Gary King, wants people to call him The King and considers himself a prince among men, but he’s the sort of guy you’d tire of quickly. His friends had enough of him long ago. They tell themselves they’ve grown up; Gary thinks they’ve sold out and become tediously conventional. To the film’s credit, neither of these points-of-view are presented as entirely wrong.

Oliver (Martin Freeman) is a fussy killjoy of a real estate agent with a Bluetooth receiver jammed in his ear at all times. Steven (Paddy Considine), an architect who was once Gary’s rival for the affections of Oliver’s sister Sam (Rosamund Pike), is recently divorced and sleeping with a young fitness instructor; he brags about that last bit to everyone who’ll listen, which is how you know he’s miserable about the rest of his life. Peter (Eddie Marsan) who was horribly bullied as a child, was always the tagalong nerd of the old group; now he sells cars for his dad. Andrew (Nick Frost) is a lawyer who refuses to speak to—or of—Gary. Gary says it’s because he still owes Andrew six hundred pounds from long ago, but we deduce that the real reason for the split is much deeper. It is. In fact it’s a doozy.

The first part of the movie consists of Gary “getting the old band back together,” as he puts it, to re-enact their great thwarted pub odyssey from 1990, when they resolved to hit all twelve nightspots in their old hometown of Newton Haven. The quiet little town is home to bars with mythologically and otherwise suggestively loaded names: The Two-Headed Dog, The Famous Cock, The Trusty Servant, The World’s End. That the pals didn’t finish their quest has always gnawed at Gary. He’s obsessed with pinning a triumphant end on a long-unfinished story.

Running beneath the lively banter and knockabout slapstick is a sense of melancholy, at times despair, over lost youth and missed opportunities. Gary is an alcoholic and drug user and chronic screwup, the sort of guy who lures other lads into joining adventures that tend to end in humiliation or disaster. He’s first seen in a rehab facility, but judging from his appearance and behavior he hasn’t been there long. Pegg looks like he just crawled out of bed—a bed at the bottom of a mine shaft, most likely—and even his most jocular pronouncements have an undertone of manic desperation. “Why should getting older affect something as important as friendship?” he demands, a question thick with unexamined assumptions.

If “The World’s End” were only a picture about childhood buddies on a bittersweet pub crawl, it might have still been some sort of minor classic, so sharply observed is every shot, cut, music cue, line and close-up. When the film takes a right turn into science fiction conspiracy thriller territory—invoking “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” as well as such Carpenter films as “The Fog” and “Prince of Darkness“—you might worry that it’s about to succumb to Gary’s biggest fear, and trade spiky if heedless individuality for a tiresome grab at commercial formula. (This is the third Wright film in which a dull community proves a hotbed of slowly-creeping and highly secretive horror.) No worries: the sci-fi elements—which were hinted at in trailers, but which I’ll write around in this review and maybe revisit later in a spoiler-warning-bedecked blog post—are audaciously funny and inventively designed, and they’re always tied to the film’s concerns. Nothing, no matter how extravagant or surreal, is superfluous.

Fears of assimilation and domestication and the loss of youthful fire are never far from the movie’s mind; neither is the altogether wise and reasonable sense that, while we should strive to be better, kinder, more mature people, we still are who we are, and if we cannot tolerate one another’s frailties and treat each other decently, there’s no hope for the species. The film has great fun painting modern life itself as a prolonged and largely invisible conspiracy to rob people and their world of all personality. Every old pub the boys revisit has been Starbucked, as they put it, and later we get the sense that the very same digitally connected world that lets you read this review on a tiny handheld computer-phone is a means of social control as well. Odd as it might sound, the unexpectedly laid back climax echoes “A Clockwork Orange.” It conveys a sense that, while a totally safe and placid and perfect world might be attainable, it’s not desirable, and might in fact be a greater sin than any act that any individual might commit.

Wright is a brilliant director of turbocharged exposition, elegant but bruising action sequences, and graphically bold comedic overkill. As in “Shaun of the Dead,” “Hot Fuzz” and “Scott Pilgrim vs. The World,” even functional closeups of beer being poured or ignition keys being turned are shot as if they were events on par with the Big Bang or the release of a new Kanye West album. Wright is a pop artist who’s not inclined to relax; at times his movies play as if he’d decided to turn the first five minutes of “Trainspotting” into a career. There are times when I wished the “The World’s End” had the confidence to linger more on the characters’ conversations and nonverbal interactions. The group’s chemistry evokes the best sad-sack male bonding tales of Barry Levinson (“Diner,” “Tin Men“), and the performances are all superb, particularly Frost, who steals the film with an explosive physicality that’s John Goodmanesque.

But in an era in which mainstream movies not only lack rhythm but seem to have forgotten how to dance, this one’s briskness is inspiring. Its judgment is nearly unerring, and it has a sense of joy that’s rare. Like most genre films, “The World’s End” is working things through in an extremely broad way and having a grand time doing it, and its self-deprecating wit inoculates it against self-importance. The movie wears its themes on its sleeve and pins its symbols to its puffed-out rooster’s chest, swaggers about with a proud grin jabbing thumbs at itself, then walks into an open manhole. It’s magnificent.