The small Jewish community in “The Women’s Balcony” is a tight-knit one. When they talk, they don’t say “I,” they say “We.” They are not just a community, they are a “congregation,” with all that that implies to the faithful. A huge box office hit in Israel, the film was written by Shlomit Nehama, and directed by Emil Ben-Shimon. “The Women’s Balcony” is an eccentric portrait of an already devout community suddenly under pressure from a super Orthodox rabbi to observe their faith in a more rigid way. While the mood is that of a gentle and affectionate comedy, the film makes some extremely sharp points about fanaticism, sexism masked as holiness, and tolerance among the faithful.

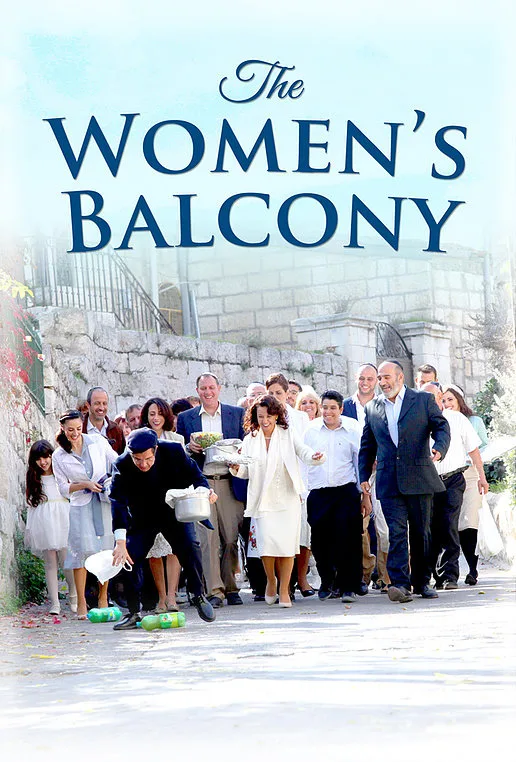

In the opening sequence, the chattering ensemble noisily traipses down a narrow street of their Jerusalem neighborhood, headed to a bar mitzvah at their local synogogue, wielding plates of food and gifts, buzzing with collective excitement. The inciting event for all that follows occurs during the bar mitzvah when the women’s balcony in the gender-segregated synagogue collapses, a collapse which puts the rabbi’s wife in the hospital, and renders the building unsafe. The elderly rabbi is thrown into a state of confusion following the collapse, a confusion bordering on dementia. This is now a flock without a leader.

During this noisy chaotic opening, we meet the ensemble. There’s longtime married couple Zion (Igal Naor), and Ettie (Evelin Hagoel), who have a relationship loving and playful. Yaffa (Yafit Asulin), Ettie’s unmarried niece, is tired of having her single status be a topic of general conversation, and is lethargic about going on more dates, despite the encouragement of all of the women around her. Rounding out the group are Ettie’s married female friends, powerhouses all, Tikva (Orna Banai), Ora (Sharon Elimelech), and Margalit (Einat Saruf), each married to a man in the congregation.

Into these well-worn and comfortable lives enters the handsome and charismatic Rabbi David (Avraham Aviv Alush). Rabbi David recognizes that this is a congregation in distress, and looks upon the collapse of the synagogue as a judgment from God. This congregation has to be whipped into shape. Nothing less, as he says, than the fate of Israel is at stake. He heads up the reconstruction project, as well as addresses what he sees to be the most pressing issue facing the congregation: the women.

Naturally. Women are front and center in most discussions of theology, in any faith: What should we do with the women? How do we keep them in their place? How do we control their sexuality? These questions were not at all factors to the “We” of the group until the cult-ish David, trailing acolytes from a nearby seminary, came along. All of the women in the congregation are devout, but none of them wear head-coverings. Rabbi David takes that on first, urging the men to make their women wear head scarves. The men, each of whom fall under the sway of the rabbi’s passionate and inspiring personality, obey, meekly bring home scarves to their baffled and irritated wives.

If that’s not bad enough, when the women learn that Rabbi David has no intention of re-building the women’s balcony in the new synagogue—that women will be banned from the main room altogether—all hell breaks loose. Marriages fracture. Men sleep on the couch. People quit smoking. Or start smoking. People go through radical personality changes. Friendships break up. It’s mayhem.

Those of us watching can see that the Rabbi David is a virus who has entered the healthy “body politic.” These people need to create some antibodies to fight him off, fast! But, of course, the characters in the midst of it can’t perceive the threat, not at first. Only Ettie can see what has really happened, saying bluntly to the Rabbi (who clocks her almost immediately as his #1 Nemesis), “Is that what a rabbi is supposed to do? Enter a community of good people and fill them with fear?”

Nehama’s script is filled with humorous one-liners (all of these people are funny), and the humor here is character-based, not just empty schtick. One cowed husband begs his cranky wife to wear the head-scarf, pleading, “It’ll help my income!” She deadpans at him, “Try working. Maybe that’ll help your income.” The script is not afraid to make its points, to really go after its true target. It’s also quite insightful about how magnetic leaders like Rabbi David can co-opt the personalities/value systems of their listeners, can stir up problems in communities that are operating just fine, head-coverings or no. These characters are used to seeing rabbis as authority figures. So when the wolf in sheep’s clothing enters their flock, they don’t have the defense mechanisms to fight him off, or even recognize him for what he is. The men, especially, are useless in the face of such male authority.

This is Emil Ben-Shimon’s first feature, and a confident debut it is. He comes from a television background, and has said that this script reminded him of the women around him when he grew up. That feeling of familiarity he has with this world, these people, breathes through every pore of “The Women’s Balcony.” Ben-Shimon recognizes what is precious (and also, at times, irritating) in a community like this one. The fanatics of this earth are not live-and-let-live people. The rabbi David sees the collapsed balcony as a judgment, mainly because the women are not submissive silent figures in the background. His misogyny is palpable, but—like many gifted religious leaders—cloaks it as admiration: “Women are so much more superior to men, aren’t they?”

A couple of years ago I reviewed a Christian film called “Faith of Our Fathers,” and bemoaned the fact that so many films about faith are poorly done, listing a bunch of films at the end of the review that deal with faith in a complex way, while never belittling those who have faith. Most recently, Martin Scorsese’s magnificent “Silence” is a mighty grappling with Catholic faith, surging with the sometimes tormented faith of its maker. “The Women’s Balcony” takes on some extremely hot topics, and in doing so makes the point powerfully that true faith does not depend on a head-scarf. True faith is alive, coursing through human relationships, made manifest in how we treat one another. “The Women’s Balcony” has its cake and eats it too. It is funny and profound.