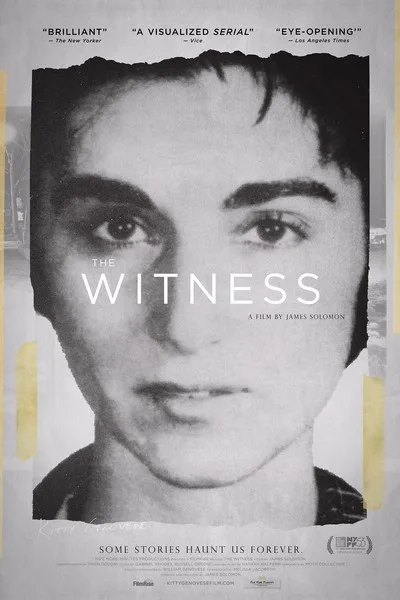

“The Witness,” screenwriter James Solomon’s documentary about the 1964 Kitty Genovese murder case, is an excellent reminder not to believe everything you read.

True crime aficionados recall the details of the case: she was a bar waitress in Kew Gardens, Queens who was randomly stabbed by a stranger named Winston Moseley—who later told police he was just looking for a woman to kill—then raped and robbed by him after he returned to finish the job. The New York Times later reported that 38 witnesses heard and even saw some part of the attack but didn’t call police and failed to intervene or even call attention to it. Like a lot of ghastly true crime tales, this one soon stopped being a simple account of a tragedy and became something bigger: a story about the anonymity and callous indifference of big cities.

Turns out that’s not how things happened. There were indeed neighbors who were aware or half-aware that something horrible was happening to a woman in the neighborhood, or at the very least that some woman was screaming, but the idea that 38 people just sat there and let it all unfold without doing anything—while remaining riveted, as if it were a radio drama or a TV show—is false. A lot of people near the scene of Genovese’s murder had no idea exactly what was going on, and there were people who tried to help or contact police.

How, then, did an untrue version of the story become enshrined as legend? The New York Times is to blame.

The film’s main character is Bill Genovese, one of Kitty’s many younger siblings. He adored his big sister and was devastated not just by losing her so suddenly and violently but by the account of her death in the Times, which went on to spur many fictional retellings, including episodes of TV’s “Perry Mason,” “All in the Family” and “Law and Order.” Bill is in a wheelchair now after losing both his legs. We eventually learn that Bill’s leglessness, too, is related to the murder—specifically to the Times’s coverage, which was not just incorrect but willfully exaggerated, to sell papers and create an American illustration of the the famous explanation of how the Nazis rose to power: evil triumphs when good people to do nothing.

If I’m making “The Witness” sound like a film about journalistic ethics, more so than a story of the Genovese family’s loss, well, it is that. For a good part of its running time, it is mainly about what happens when the institutions we entrust to tell our stories fail us.

Bill is our surrogate, chasing down the real story for reasons of personal catharsis. The information he gleans by studying coverage of the case and contacting the reporters tells us a lot about the relationship between a free press and the society it chronicles. The film insists that for every benefit accrued by telling a wrong or concocted story—such as the invention of the 911 emergency system, which came about partly as a result of the public feeling collectively ashamed of itself after Genovese’s murder—there are downsides as well, some severe.

One major, negative bit of fallout from Genovese murder coverage was a hyped-up perception of cities as coldblooded places where people don’t know or care what happens to their neighbors. That might be true in certain situations, but not in this one—perhaps not in most. When groups of people behave callously or indifferently to violence or suffering, it’s rare that every single person who’s aware of it doesn’t care enough to lift a finger. Bill ultimately learns that people on his sister’s block did, in fact, act like members of a community, but unfortunately many of them didn’t know exactly what was happening or had no way of effectively acting as a group. It even turns out that somebody did call the police about Genovese; the police just failed to respond properly.

“The Witness” might have benefited from a more thorough exploration of these and other issues, in particular the New York Times‘ arrogant indifference to the facts of this case. A retired reporter for the long-defunct New York Herald Tribune tells Bill that he thought their Genovese story seemed back way in 1964, but that when he confronted the original Times reporter about inconsistencies and mistakes (such as the number of witnesses and what they knew) he was told, in essence, “Let it go—it’s a compelling story, what are you trying to do, ruin it?”

A.M. Rosenthal, who was the New York Times’ city editor for the paper during Genovese coverage and later became executive editor, an editorial page columnist, and then a columnist for the New York Daily News, expresses more or less that point-of-view in an interview conducted before his death in 2006. Rosenthal wrote an entire acclaimed book about the case, “38 Witnesses” (the very title of which is apparently wrong; the Herald Tribune reporter says there were 37). The Genovese story misleadingly became a metaphor for urban apathy. But in conversation with Bill Genovese, Rosenthal seems to think that his paper’s coverage was ultimately so important (in part because it led to the 911 emergency response system) that it doesn’t matter which parts were right or wrong. (Although the movie doesn’t get into this, the paper under Rosenthal supported the U.S. invasion of Iraq, which was at least partly motivated by information that was later proved to be exaggerated or false. It also doesn’t get into the Genovese story as part of a growing 1960s hostility toward the idea of the big city, an era during which automobile-dominated suburbs were being sold to Americans as peaceful Edens where only hardworking, decent people lived.)

Though the press abuse angle is infuriating, the story of Bill, his siblings, his parents and his friends is devastating. The movie shows how extraordinary events (such as murder) can complicate the grieving process. Bill and his brothers tell the filmmaker that they were so young when Kitty died that they don’t really know her as a person, and as they grew up, they were so consumed with the idea of Genovese-as-symbol that they never learned the details of her life prior to the attack. Bill discusses some of those details in this movie, and the result might be the most satisfying and moving part of the story. You watch and listen as an emblematic character, basically an issue plus a name, is filled in, to the point where she becomes fully human onscreen, maybe for the first time since TV and film began retelling the story of her death. This is a powerful movie, but perhaps its greatest triumph is that for a brief time it resurrects Kitty Genovese and lets us see her as a person.