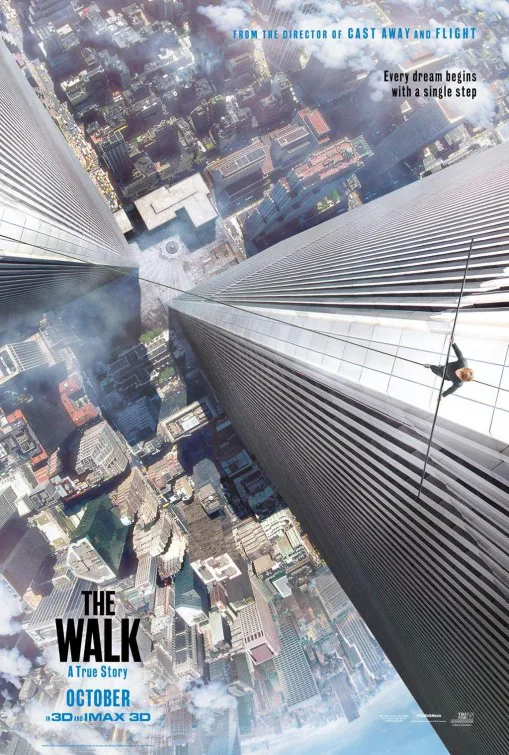

In terms of sheer directorial craft, “The Walk” is masterful, but as storytelling, it’s a near-disaster.

That’s too bad, because nobody does visceral like Robert Zemeckis. Even in his less-than-great films, there are always two or three sequences that dazzle the viewer, often by evoking the sights and sounds of an extraordinary experience in such a way that you feel as if you’re participating in them along with the characters. “The Walk,” Zemeckis’ account of Phillippe Petit’s 1974 tightrope walk between the Twin Towers of the old World Trade Center, would seem to be the ultimate Zemeckis set piece, rivaling the awesomeness of the plane crash and island sequences of “Cast Away,” the upside-down jet maneuver in “Flight,” the intergalactic wormhole trips in “Contact,” and the small-scaled relentlessness of the suspense sequences in his under-appreciated 2000 thriller “What Lies Beneath” (which wrung tremendous excitement from the question of whether a nearly paralyzed woman could use her big toe to remove the stopper from a bathtub drain).

The final half-hour of “The Walk” is on that level. It’s hard to imagine how it could have done a better job imagining every physical detail of the hero’s unmatched physical achievement. Following the movie’s New York Film Festival premiere, there were reports of people throwing up in the men’s room after suffering virtual vertigo while watching Petit (played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt) stroll, turn and even lie down upon a cable stretched between the towers. In this respect, “The Walk” does not disappoint. Zemeckis is on a short list, along with Steven Spielberg and Alfred Hitchcock, of filmmakers who understand how to fuse audacity with simplicity, so that the scale of the flourishes in their biggest sequences is wed to recognizable emotions. He makes sure that you don’t just understand how Petit did what he did, but what he might have been feeling during every step of his journey, and what he saw and heard. The metallic creak of the cable as Petit walks; the rustle and hiss of wind passing over his clothes and through his hair; the muffled sound of traffic noises floating up from 110 stories below: “The Walk” makes these and other sensations palpable, along with Petit’s delight, defiance and moments of doubt and fear.

If only Zemeckis had faith in his filmmaking power! What “The Walk” is missing, unfortunately, is an ability to recognize when poetry and mystery are enough and should be left alone to breathe. Here is a movie about a man whose life was defined by a daring, unprecedented and now un-repeatable artistic feat (transforming boxy skyscrapers into a stage high above North America’s largest city) and who achieved that feat by trusting in his training and bravery and will. But the script, credited to Zemeckis and Christopher Browne, begins diminishing his achievement immediately with tedious chatter, and can’t stop doing it.

The movie kicks off with a poorly CGI’d (for Zemeckis) shot of the hero standing in the Statue of Liberty’s torch with the Towers looming across the water behind him, talking and talking and talking not to you but at you, often in bizarrely gargoyle-ish close-ups, about the amazing thing he’s about to do, or is doing—as if convincing us to buy a ticket to the film we’re already sitting there watching.

“You’re doing too much!” warns the hero’s mentor (scene-stealer Ben Kingsley) early in the movie. “Do nothing!” The movie ignores its own advice. If the point were to show how the hucksterish aspect of Petit diminished his physical feats, and paint a portrait of an insufferable and in some ways untrustworthy salesman-adventurer who’s in love with himself, it might have been defensible, but that’s not the case. We’re supposed to take everything Petit says at face value. We’re supposed to adore him. His narration is an insurance policy intended to guarantee audience involvement and make sure we never fail to understand any point.

“The Walk” starts selling itself to you the second you settle into your chair (“To walk on the wire, this is life!” Petit tells us, jamming his face into the lens). It keeps selling and selling and selling itself, telling you how amazing and wondrous everything is via voice-over and straight-into-the-camera narration, verbally explaining things that Zemeckis’ images are already doing a peerless job of showing you, sometimes breaking the movie’s spell by having the hero chime in with an observation that’s nowhere near as eloquent as the sight of Petit doing what only Petit can do. Petit’s narration might be the most counterproductive and irritating narration ever to be glommed onto a potentially great motion picture. Suffering through it is like visiting the Grand Canyon or the Metropolitan Museum of Art with someone who keeps exclaiming how incredible and astonishing everything is every fifteen seconds, to the point where you want to leave and come back the next day by yourself so that you have an actual experience.

“And with this pencil stroke, my fate was sealed,” the narration tells us, over images of Petit drawing a line between the towers as depicted in a magazine ad that he peruses while waiting to see a doctor—as if we couldn’t figure out why that moment is important, in a movie about a guy who tightrope-walked between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. “This is the beginning of my dream!” The nadir of the movie’s poor judgment occurs during its still-mostly-astonishing climax, when Petit lies down on the cable, engulfed in misty cloud cover, and watches a lone gull hovers over him and seems to stare into his eyes, as if wondering if he’s some kind of bird, too. The moment has the eerie mesmerizing power of an incantation, but sure enough, here comes Petit in voice-over telling us about how this bird came out of the clouds and hovered there over him and dammit, movie, don’t you know we have eyes and ears?

I don’t believe in the admonition “show, don’t tell.” It’s a maxim cited by hack screenwriters who make money from how-to books and seminars, not from actual screenwriting. Some of the greatest films in cinema history have active, insistent, even constant narration. But such films are not just telling in place of showing. They’re showing while they’re telling and telling while they’re showing, and the verbal component adds to, and often complicates or subverts, the images and sounds. That’s not the case here. Aside from a few practical observations about being an acrobat, there is nary a word of Petit’s narration that couldn’t be red-lined for redundancy. If what you want is to hear people talk about Petit (including Petit), you might as well buy a copy of the memoir upon which the “The Walk” is based, or watch James Marsh’s great 2008 nonfiction film “Man on Wire,” which includes so many re-enactments that it’s half a drama, anyway.

“The Walk” is worth seeing on a big screen for its final wire walk (intrusive voice-over notwithstanding), for its lovingly recreated images of the World Trade Center, for its often wry humor (including a marvelous running gag involving an elevator operator) and for some of the supporting performances (notably Kingsley’s pitch-perfect mentor performance, and James Badge Dale’s turn as a wise-ass Franco-American who joins the team infiltrating the towers). Gordon-Levitt is verbally miscast (his Franch acc-SANT is too theatrical and might make you wish they’d cast an actual French actor) but physically convincing; you buy him as a man driven to achieve the impossible, and willing to do the hard work necessary to hone his skills, and you also believe him as a charismatic, selfish leader whose hint of madness is as attractive as it is troubling. But this is ultimately a frustrating work. “The Walk” has everything it needs to be a modern classic, except for an understanding that when you have everything you need to make a such a film, it doesn’t need to hype itself and explain itself. It can just be.