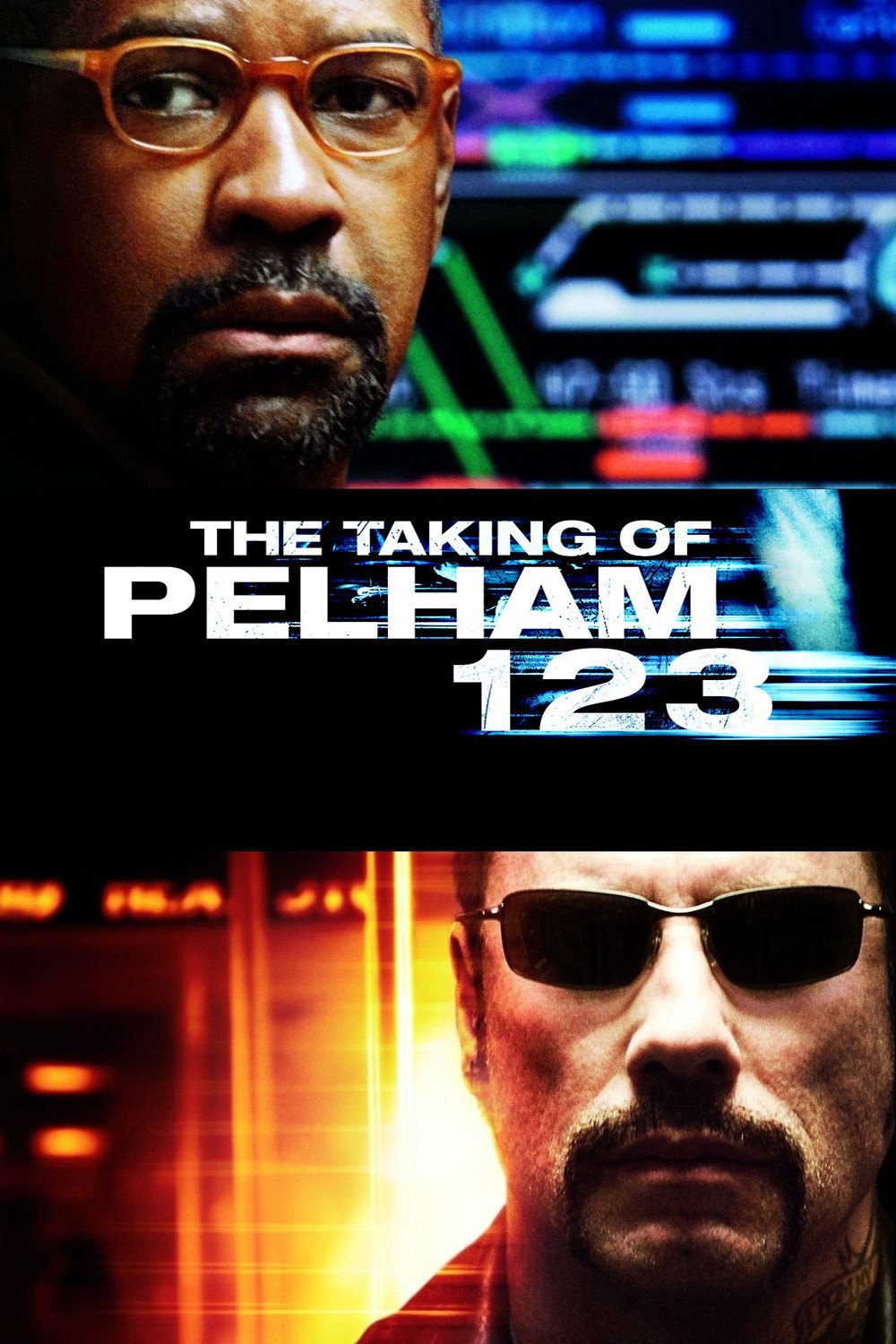

There’s not much wrong with Tony Scott’s “The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3,” except that there’s not much really right about it. Nobody gets terrifically worked up, except the special-effects people. Oh, John Travolta is angry and Denzel Washington is determined, but you don’t sense passion in the performances. They’re about behaving, not evoking.

The story you already know from cable TV. There are a few changes: The boss hijacker is now an ex-con instead of a former mercenary. The negotiator is now a transit executive, not a cop. The ransom has gone up from $1 million to $10 million. The special effects are much more hyperkinetic and absurd than before, which is not an improvement. When a police car has a high-speed collision, the result is usually consistent with the laws of gravity and physics, unlike in this film. It does not take flight and spin head over heels in the air.

The Washington and Travolta roles were played the first time around by Walter Matthau and Robert Shaw. They fit into them naturally. Matthau in particular had a shaggy charm I am nostalgic for. Shaw brought cold steel to his performance. Denzel is … nice. Sincere. Wants to clear his name. Travolta is so ruthless, it comes across as more peremptory than evil.

Since time immemorial, Vehicular Disaster Epics have depended on colorful and easily remembered secondary passengers: Nuns with guitars, middle-aged women with swimming medals, a pregnant woman about to go into labor, etc. This time, the passengers on the Pelham line disappoint. There’s a nice woman who’s worried about her child, and an ex-Army Ranger who comes to her aid. That’s about it. Few of the juicy ethnic stereotypes of the original.

In fact, the whole film is less juicy. The 1974 version took place in a realistic, well-worn New York City. This version occupies a denatured action-movie landscape, with no time for local color and a transit system control room that humbles Mission Control. That also may explain the film’s lack of time to establish the supporting characters, even Travolta’s partners. These sleek modern actioners don’t give the audience credit for much patience and curiosity. One star or the other has to be on the screen in almost every scene. The relentless pace can’t be slowed for much dialogue, especially for supporting characters. It all has to be mindless, implausible action.

Say what you will about the special effects of the 1970s, at least I was convinced I was looking at a real train. Think this through with me: Once you buy into the fact that the train is there, the train becomes a given. You’re thinking, ohmigod, what’s going to happen to the train? With modern CGI, there are scenes where a real train is obviously not on the screen, at least not in real time and space, and you’re thinking, ohmigod, real trains can’t go that fast.

And when cars crash, cars should crash. They shouldn’t behave like pinballs.

Note: Here’s an interesting thing. Looking up my 1974 review (“The Taking of Pelham One Two Three“), I found that four of the characters were named Blue, Green, Gray and Brown. Could it be that when Quentin Tarantino was writing about Mr. White, Mr. Orange, Mr. Blonde and Mr. Pink in “Reservoir Dogs,” he was — naw, it’s gotta be just a coincidence.