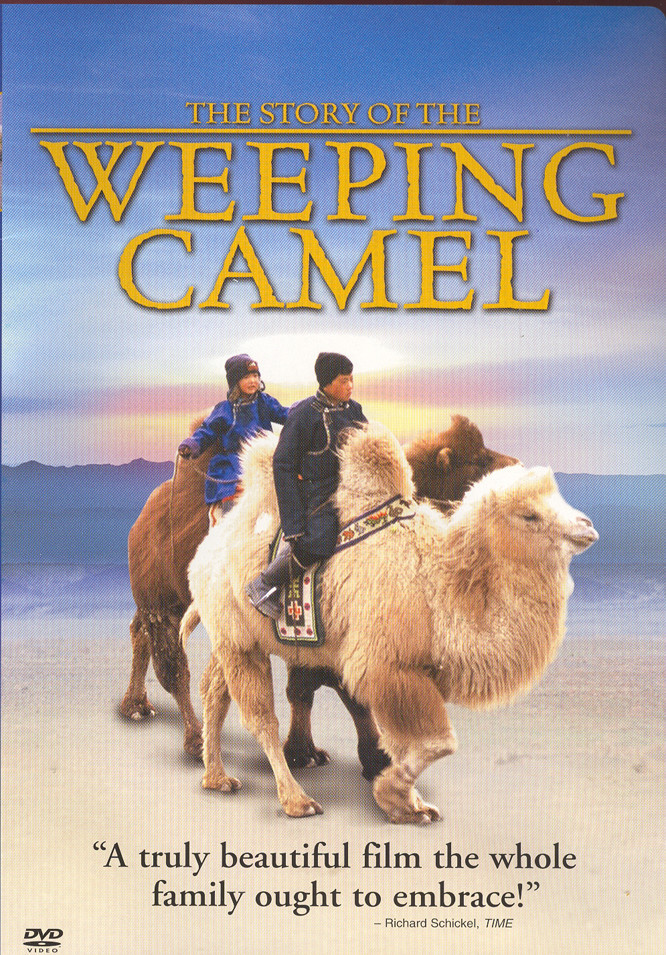

On the edges of the Gobi Desert live to this day nomadic herders who travel with their animals and exist within an ancient economy that requires no money. “The Story of the Weeping Camel,” which despite its title, is a joyous movie, tells the story of one of those families, and of their camel, which gives birth to a rare white calf and refuses to nurse it. It is a terrible thing to hear the cry of a baby camel rejected by its mother.

The movie has been made in the same way that Robert Flaherty made such documentaries as “Nanook of the North,” “Men of Aran” and “Louisiana Story.” It uses real people in real places and essentially has them play themselves in a story inspired by their lives. That makes it a “narrative documentary,” according to the filmmakers. A great many documentaries are closer to this model than their makers will admit; even “cinema verite” must pick and choose from the available footage and reflect a point of view.

We meet four generations of the same family. Do not think of them as primitive; it takes great wisdom to survive in their manner. I learn from the press materials that the older brother, Dude (Enkhbulgan Ikhbayar) went away to boarding school but then returned to his family because he enjoyed the way of life. Certainly these people live close to the land and to their animals, and their yurts are masterpieces of construction — sturdy portable homes that can be carried on the back of a camel but are sturdy enough to withstand winter storms.

It is spring when the movie begins, and a mother camel (Ingen Temee) has just given painful birth to her white calf (Botok). It is only reasonable to supply the names of these animals, since they are so much a part of their nomad families. Does the mother refuse her milk because the calf looks strange to her, or because of her birth agony? No matter; unless the calf is fed, it will die, and the family needs it.

When bottle-feeding fails, Dude and his younger brother Ugna (Uuganbaatar Ikhbayar) travel by camel some 50 kilometers to the nearest town, to bring back a musician who will play a traditional song to the camel and perhaps persuade it to relent. While in the village, they watch television and brush against other artifacts of modern life, with curiosity but without need.

The musician accompanies them to the village. He plays the traditional song. Legend has it that if a camel finally agrees to nurse her young, this will cause her to weep. There are also a few damp eyes among members of the family. All of this is told in a narrative that is not a cute true-life animal tale, but an observant and respectful record of the daily rhythms and patterns of these lives. We sense the dynamics among the generations, how age is valued and youth is cherished, how the lives of these people make sense to them in a way that ours never will, because they know why they do what they do, and what will come of it. The causes and effects of their survival are visible, and they are responsible.

The filmmakers are Byambasuren Davaa and Luigi Falorni. She directed, he photographed, they co-wrote. They met at the Munich Film School, where she told him that her grandparents had been herders. Their film was shot on location in about a month, and has an authenticity in its very bones. In a commercial movie, sentiment would rule, and we would feel sorry for the cute baby camel. Well, yes, we feel sorry for the calf in “The Story of the Weeping Camel,” but we also understand that the camel represents wealth and survival for its owners, and in what they do they’re thinking, as they should, more about themselves than about the camel.

I believe this film would be fascinating for smart children, maybe the same ones who liked “Whale Rider,” because so much of it is told through the eyes of the younger brother. Although the desert society is alien to everything we know, in another way it is instantly understandable, because we know about parents and grandparents, about working to put food on the table, about the need of babies to nurse. Here is a film that is about life itself, and about those few humans who still engage it at first hand.

Note: Two other splendid documentaries cover similar ground. “Taiga” (1995), the remarkable eight-hour documentary by Ulrike Ottinger, lives and travels with nomads for a year, and witnesses their private lives and religious ceremonies.

“Genghis Blues” is the wonderful 1999 documentary about a blind San Francisco blues singer who hears Tuvan throat singing on the radio, teaches himself that difficult art and then journeys to Tuva, which is between Mongolia and Siberia, to enter a throat-singing contest.