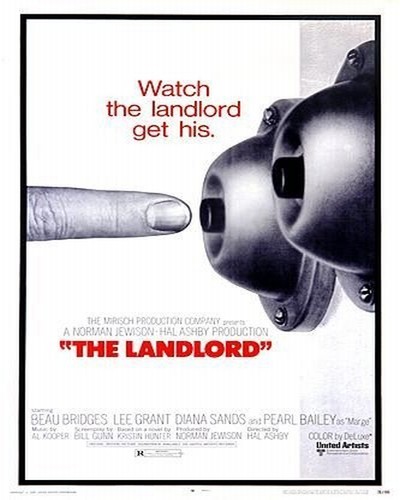

Hal Ashby’s “The Landlord,” as you’ve probably already heard, is about a rich white society kid who lolls around the old plantation until he’s 29, then ups and buys himself a tenement in a black ghetto one day. “Everyone,” he reflects while sunning himself beside the family pool, “wants a home of his own, you know.”

So he moves in, installs new plumbing, makes plans to hang a chandelier from the skylight over the stairs, and meets the tenants. They’re a pretty mixed bag, ranging from a Black Nationalist to Miss Sepia of 1957. He never does meet the old couple in the basement, who keeps their shades pulled and apparently never come outdoors. But he’s invited in for soul food by the palm-reader on the second floor (Pearl Bailey).

Until about this point, “The Landlord” is more or less what I was expecting: A situation comedy with the white kid (Beau Bridges) as straight man. Like, Pearl pleads with Beau to eat some more of them good ham hocks, and you gotta smile, right? But then the movie takes an interesting turn. Instead of staying on that safe, predictable level, it begins to dig into the awkwardness and hypocrisy of our commonly shared, attitudes about race.

The tenants throw a rent party, for example, and as the booze and the music begin to reach the landlord, the scene gradually becomes surrealist and the tenants start telling him in plain language what black means to them. He gets involved with Miss Sepia of 1957 (played with beautiful tenderness by Diana Sands), and they make love, and she says, “You know it didn’t mean anything, don’t you? Because I’m in love with Copee.”

Copee is her husband, and she does love him, and he needs her because he’s perhaps a little mad. He’s into a black militant thing just now, she explains, but before that he spent two years as a Sioux Indian. All very well, until it turns out she’s pregnant and the child belongs to the landlord….

He’s having some very heavy problems of his own, trying to figure out about race. He goes to a black discotheque and dances with a girl he thinks is white. He asks her if she’s, uh, a VISTA volunteer? She explains that, in fact, she’s black; this is clearly a surprise to him, but after he’s slept with Miss Sepia of 1957 he finds out something (I don’t know just what) that makes him feel “free” to fall in love with the dancer. (He’s kind of a jerk, as you can see, but that’s the point of the film.)

Anyway, all these threads become more and more tangled, and they’re seen against the background of his incredibly rich, stupid family.

Lee Grant contributes a pathetic and hilarious portrait of his mother; she goes to the tenement in her chauffeur-driven limousine one day to measure his apartment for curtains, and winds up on the floor with Pearl Bailey, drinking pot liquor and getting mystical. But they cannot accept their son’s life, and although he goes through the motions of “rejecting” them, he can’t handle the implications of his decision.

After Copee’s wife has the landlord’s baby, for example, the landlord visits her and makes it clear, in a shifty sort of way, that he’s not going to be responsible. She refuses to take the baby home to Copee because she loves Copee and couldn’t do that to him the landlord won’t take the baby because, uh, what in God’s name would he, uh, do with a baby?

So she says she wants the baby adopted white. And then she looks him very deeply in the eye and explains why: “I want him to be adopted white so he can grow up casual. Like his daddy.”

This kind of dialog is both simple and very strong, and the movie has a lot of it. It adds up to a more honest, if less optimistic, portrait of American race relations than we usually see in the movies.

‘The landlord emerges as essentially a hobbyist; he’s bought the tenement as a self-indulgence, but he doesn’t really want to cope with the problems he finds behind its doors. And the black people inside, while they treat him decently and openly, seem to know from the first that he’s a visitor to this block of the city, and not a neighbor. Even if he does own a home of his own.