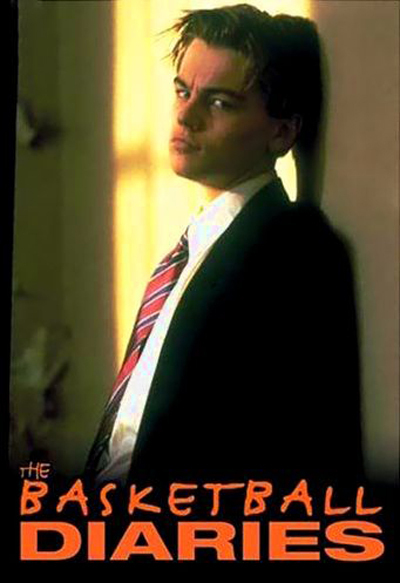

Jim Carroll’s cult book The Basketball Diaries, published in 1978, describes in grungy detail how the author passed in a few short months from being a Catholic high school basketball star to being a strung-out heroin addict who turned tricks for drugs. Like many such stories, it lingers lovingly over the horrors, and ends with unseemly haste after happiness is regained.

Will there ever be a market for a movie about a character who hurries past his drug phase because he can’t wait to tell you what he did after he pulled his act together? Probably not. If there’s anything more boring than a juicy parable with a moral at the end, it’s the moral without the parable. And so “The Basketball Diaries” informs us in great detail that if you get strung out on drugs, you are likely to find yourself living desperately on the streets, peddling a body that looks less and less like a good buy.

Of course the Carroll book was more than this; he struck a personal note, of a kid who despite his suffering tried to turn his experience into poetry. The problem with Scott Kalvert’s film is that the camera tends to make the experiences too literal: Jim, the hero of the story, is so desperately sick and unhappy that the romanticism seems unconvincing. He plays basketball at night in the rain after his best friend dies of leukemia, and it just looks wet, not touching.

As the movie opens, Jim (Leonardo DiCaprio) is on the basketball team at St. Vitus High School in New York, where a perverted priest salivates while spanking naughty students with a big paddle and the rest of the class watches. This scene owes more to Victorian pornography than to any actual parochial school in 20th century America, but no matter: The message, I guess, is that the teachers are such hypocrites you might as well go out and destroy yourself.

Jim and his friends are not good Catholic lads. The student manager of the basketball team steals from the lockers of the opposing team, and the favorite off-court pastime is experimenting with inhalants and pills. The coach, named Swifty and played by Bruno Kirby, is a closet homosexual who spends great effort making unlikely passes at Jim (“Do we understand each other?” he asks in the shower room, offering money). And Jim’s mother, played by Lorraine Bracco, is a one-dimensional character who exists in the movie solely to exercise Tough Love by throwing him out.

Life for Jim is a downward spiral of pills, cough medicine, booze, jumping off cliffs into the Harlem River, passing out during a game and masturbating under the stars (the movie heroically declines to score this scene with “Up on the Roof”). There are also exciting glimpses into the underworld of users, pushers, hookers and pimps, as Jim drifts loose from his secure moorings, while writing everything down in his diary.

Jim’s poetry serves as a narration for part of the film. Like most poetry written by teenagers, it is puerile romanticism, painfully sincere, viewing life as tragic because the author is not happy. Soon, however, he is happy. He tries heroin, and “any ache or pain or sadness or guilt was completely flushed out.” Amazing, how real life has a way of unfolding just like the movies. The movie depends on three durable cliches: (1) Jim helps his dying friend escape from the hospital so he can push his wheelchair down 42nd Street (the movies know that hospitals kill and the only cure is freedom); (2) Jim sees his teammate Neutron on TV, playing in an all-star game while Jim is in a Skid Row bar (one always happens to see on TV exactly what the story requires); (3) Jim is saved by a noble black man, who finds him unconscious in a playground, brings him home and puts him through cold turkey (in stories like this, you can always count on a heroic black ex-junkie, scouring the streets for troubled white kids who need to get whupped into shape; there’s just not the same cachet in being saved by a white dude).

DiCaprio (“What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?”) does what he can with the part but is miscast, I think, as the hard-boiled hero. Ernie Hudson is strong as the ex-junkie, and there is real emotion in Lorraine Bracco’s underwritten mother. Oh, and Juliette Lewis, as a scuzzy hooker, once again finds an absolutely authentic note. But the movie is unconvincing. At the end, Jim is seen going in through a “stage door,” and then we hear him telling the story of his descent and recovery. We can’t tell if this is supposed to be genuine testimony or a performance. That’s the problem with the whole movie.