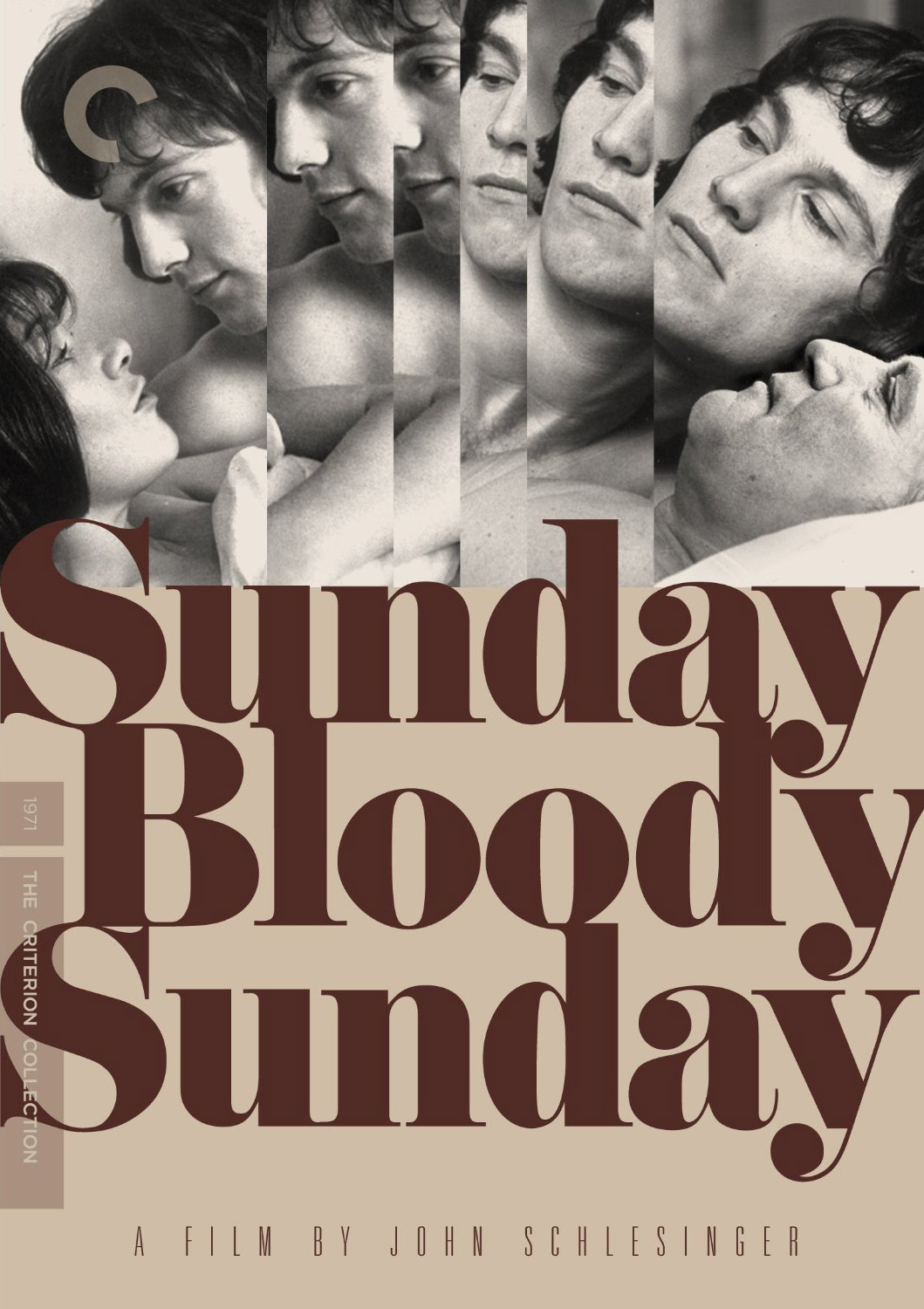

The official East Coast line on John Schlesinger’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday” was that it is civilized. That judgment was enlisted to carry the critical defense of the movie; and, indeed, how can the decent critic be against a civilized movie about civilized people? My notion, all the same, is that “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is about people who suffer from psychic amputation, not civility, and that this film is not an affirmation but a tragedy.

The story involves three people in a rather novel love triangle: A London doctor in his forties, a divorced woman in her thirties, and the young man they are both in love with. The doctor and the woman know about each other (the young man makes no attempt to keep secrets) but don’t seem particularly concerned; they have both made an accommodation in order to have some love instead of none at all.

The screenplay by Penelope Gilliatt takes us through eight or nine days in their lives, while the young man prepares to leave for New York. Both of his lovers will miss him — and he will miss them, after his fashion — but he has decided to go, and between them, they don’t have enough pull on him to make him want to stay. So the two love affairs approach their ends, while the lovers go about a melancholy daily existence in London.

Both the doctor and the woman are involved in helping people, he by a kind and intelligent approach to his patients, she through working in an employment agency. The boy, on the other hand, seems exclusively preoccupied with the commercial prospects in America for his sculpture (he does things with glass tubes, liquids, and electricity). He isn’t concerned with whether his stuff is any good, but whether it will sell to Americans. He doesn’t seem to feel very deeply about anything, in fact. He is kind enough and open enough, but there is no dimension to him, as there is to his lovers.

It is with the two older characters that we get to the core of the movie. In a world where everyone loses eventually, they are still survivors. They survive by accommodating themselves to life as it must be lived. The doctor, for example, is not at all personally disturbed by his homosexuality, and yet he doesn’t reveal it to his close-knit Jewish family; maintaining relations-as-usual with them is another way for him to survive. The woman tells us late in the film, “Some people believe something is better than nothing, but I’m beginning to believe that nothing can be better than something.” Well, maybe so, but we get to know her well enough to suspect that she will settle for something, not nothing, again the next time.

The glory of “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is supposed to be the intelligent, sophisticated — civilized! — way in which these two people gracefully accept the loss of a love they had shared. Well, they are graceful as hell about it, and there is a positive glut of being philosophical about the inevitable. But that didn’t make me feel better for them, or about them, the way it was supposed to; I felt pity for them. I insist that they would not have been so bloody civilized if either one had felt really deeply about the boy. The fact that they were willing to share him is perhaps a clue: They shared him not because they were willing to settle for half, but because they were afraid to try for all. The three-sided arrangement was, in part, a guarantee that no one would get in so deep that being “civilized” wouldn’t be protection enough against hurt.

The acting is flawless. Peter Finch is the doctor, Glenda Jackson the woman, and Murray Head the young man. They are good to begin with and then just right for Gilliatt’s screenplay and Schlesinger’s direction. They are set down in a very real and sad London (seen mostly in cold twilights), and surrounded by supporting actors who resonate in a way that fills in all the dimensions of the characters. I think “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is a masterpiece, but I don’t think it’s about what everybody else seems to think it’s about. This is not a movie about the loss of love, but about its absence.