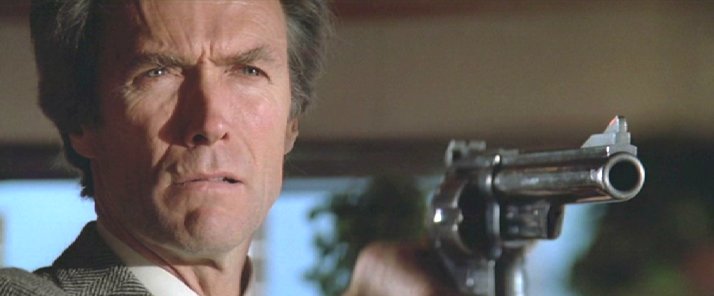

Most of what you hear about pop art and pop culture is pure hype. But there comes a moment about halfway through “Sudden Impact,” the new Dirty Harry movie, when you realize that Harry has achieved some kind of legitimate pop status, as the purest distillation in the movies of the spirit of vengeance. To all those cowboy movies we saw in our youth, all those TV Westerns and cop dramas and war movies, Dirty Harry has brought a great simplification: A big man, a big gun, a bad guy and instant justice.

We learned early to cheer when John Wayne shot the bad guys. We cheered when the Cavalry turned up, or the Yanks, or the SWAT Team. What Eastwood’s Dirty Harry movies do is very simple. They reduce the screen time between those cheers to the absolute minimum.

“Sudden Impact” is a Dirty Harry movie with only the good parts left in. All the slow stuff, such as character, motivation, atmosphere and plot, has been pared to exactly the minimum necessary to hold together the violence. This movie has been edited with the economy of a 30-second commercial. As a result, it’s a great audience picture. It’s not plausible, it doesn’t make much sense, it has a cardboard villain and, for that matter, a hero who exists more as a set of functions (grin, fight, chase, kill) than as a human being. But none of those are valid objections.

“Sudden Impact” is more like a music video; it consists only of setups and payoffs, its big scenes are self-contained, it’s filled with kinetic energy, and it has a short attention span. That last is very important, because if anyone were really keeping track of what Callahan does in this movie, Harry would be removed from the streets after his third or fourth killing. Dirty Harry movies are like Roadrunner cartoons; the moment a body is dead, it is forgotten, and nobody stands around to dispose of the corpses.

The movie’s basically a revenge tragedy. A young woman (Sondra Locke) and her sister are sexually attacked at a carnival by a group of quasi-human bullies. The sister goes nuts, and Locke vows vengeance. One by one, she tracks down the rapists, and murders them by shooting them in the genitals and forehead. Dirty Harry gets assigned to the case, and the rest is a series of violent confrontations.

Occasionally there’s comic relief, in the form of Harry’s meetings with his superiors, and his grim jawed put-downs of anyone who crosses his path. (“Suck fish heads,” he helpfully advises one man.) If the movie has a weakness, it’s the plot. Because I’m not sure the plot is relevant to the success of the film, I’m not sure that’s a weakness.

The whole business of Locke’s revenge is so mechanically established and carried out that it’s automatic, and because she has a “good” motive for her murders, she doesn’t make an interesting villain. If Eastwood could create a villain as single-minded, violent, economically chiseled and unremittingly efficient as Dirty Harry Callahan, then we’d be onto something.