Guy Ritchie’s “Revolver” is a frothing mad film that thrashes against its very sprocket holes in an attempt to bash its brains out against the projector. It seems designed to punish the audience for buying tickets. It is a “thriller” without thrills, constructed in a meaningless jumble of flashbacks and flash-forwards and subtitles and mottos and messages and scenes that are deconstructed, reconstructed and self-destructed. I wanted to signal the projectionist to put a gun to it.

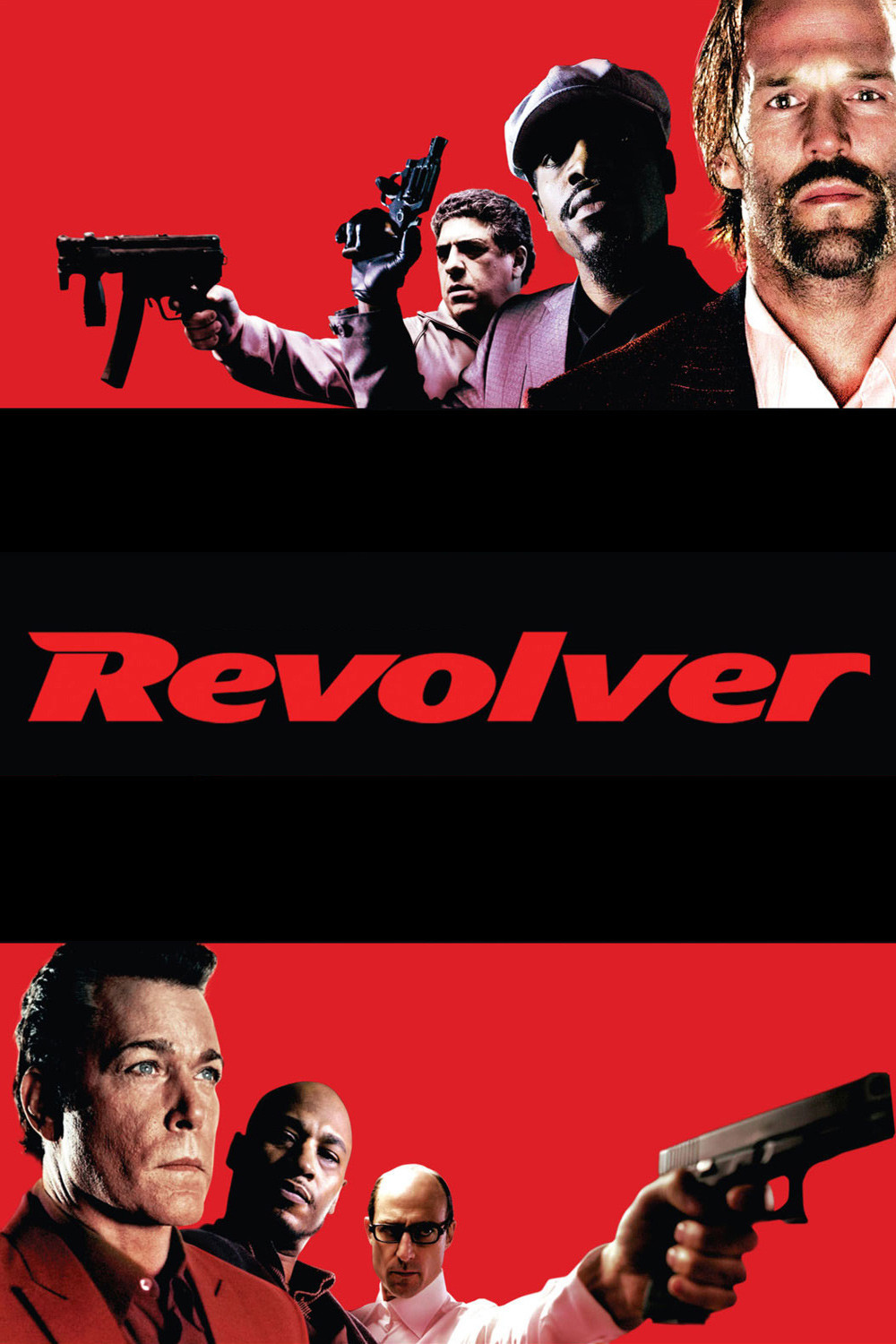

The plot. What is the plot? Jason Statham has spent seven years in jail, between a con man in the cell on one side and a chess master on the other. Back on the street, he walks into a casino run by his old enemy Ray Liotta and wins a fortune at the table. Did he cheat, or what? I dunno. Liotta sics some hit men on him. Then two mysterious strangers (Vincent Pastore and Andre Benjamin) materialize in Statham’s life at just such moments when they are in a position to save it. Who, oh who, could these two men, one of whom plays chess, possibly be?

The movie (made in 2005 but just now getting a U.S. release) begins with a bunch of sayings which will be repeated endlessly like mantras throughout the film. Chris Cabin at filmcritic.com thinks these have some connection with the Kabbalah beliefs of Ritchie and his wife, Madonna. I know zilch about Kabbalah, but if he’s right, and if Ritchie follows them, I would urgently warn other directors to stay clear of Kabbalah. Judging by this film, it encourages you to confuse hopeless confusion with pure reason.

Oh, this film angered me. It kept turning back on itself, biting its own tail, doubling back through scenes with less and less meaning and purpose, chanting those sayings as if to hammer us down into accepting them. It employed three editors. Skeleton crew.

Some of the acting is better than the film deserves. Make that all of the acting. Actually, the film stock itself is better than the film deserves. You know when sometimes a film catches fire inside a projector? If it happened with this one, I suspect the audience might cheer.