Martin is a blind man who believes anyone might be lying to him.

His lack of trust, which runs so deep it has defined his entire life and personality, began in childhood. It was his mother’s custom to describe the garden outside his window to him. One day she told him there was a man raking leaves in the garden. Martin could hear nothing, and decided his mother was lying. He used a camera to take a photograph of the garden.

When we meet Martin, in the opening scenes of “Proof,” years have passed, but he is still a photographer. It is his way of checking up on his friends. He takes pictures, has them developed, asks people to describe them to him, labels them in Braille, and is alert to any contradictions in what people tell him. Martin lives alone, in a rigid and compromising lifestyle, and is fiercely independent. If he feels he is being overlooked in a restaurant, for example, he is capable of taking a bottle of wine and pouring it out on the table until a waiter takes notice.

Celia is Martin’s housekeeper. Actually, she doesn’t need the work to support herself. It is her way of getting into Martin’s life. She is a photographer herself. Her walls are covered with photos of Martin. Their relationship is prickly and marked by anger; perhaps Celia enjoys the sharp edge of every conversation.

One day Martin, to his amazement, makes a friend, Andy, who works in the restaurant. They start hanging out together, which offends the possessive Celia.

And so the long-established patterns of Martin’s life begin to change, as Celia uses her sexuality as a device to control both men.

The ending of the film is a release of pent-up tension, a calling-due of all the emotional bills that Martin has never been willing to pay.

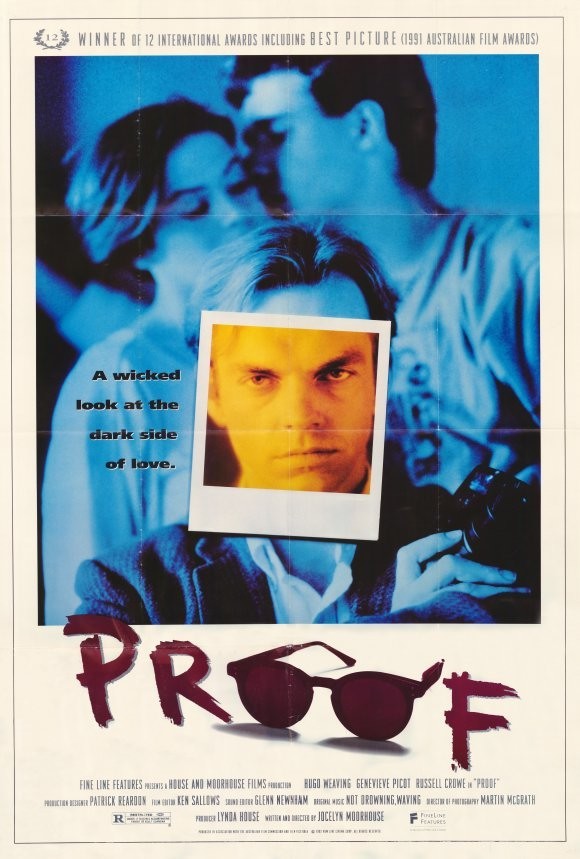

And everything comes back to that picture he took of the garden: Was his mother lying to him, or not? “Proof” is a first film from Australia, written and directed by Jocelyn Moorhouse, who has the gift of creating characters who are interesting just because of who they are. The movie doesn’t depend on a contrived plot or any manufactured surprises. It simply introduces us to Martin, Celia and Andy, and the situation Martin has carefully made for himself, and as they develop their games of power and control, we become completely absorbed.

Martin, played by the tight-faced, rigidly controlled Hugo Weaving, is an original, a man who has protected himself so completely against the possibility of being hurt that he has cut off the possibility of feeling.

Celia’s need for just this sort of man is the most interesting thing about her. Andy is an innocent compared to the other two.

Moorhouse has a way of putting all the pieces into place for a scene, so that it pays off in ways we could not anticipate.

Observe, for example, the scene in the park, when Martin doesn’t realize that the others are there. His camera becomes the occasion for comedy at the beginning, and for a troubling payoff later on. Or look at the way Moorhouse uses that original photo, the one of the garden which might or might not be empty.

If there is a kind of movie I like better than any other, it is this kind, the close observation of particular lives, perhaps because it exploits so completely the cinema’s potential for voyeurism. There are not good or bad people here, simply characters driven by their needs and insecurities into a situation where something has to give. What could be more interesting?