“Prick Up Your Ears” is the story of Orton and Halliwell and the murder. They say that most murderers are known to their victims. They don’t say that if you knew the victims as well as the murderer did, you might understand more about the murder, but doubtless that is sometimes the case. This movie opens with a brutal, senseless crime. By the time the movie is over, the crime is still brutal, but it is possible to comprehend.

When they met, Orton was 17, Halliwell was 25 and they both wanted to be novelists. They were homosexuals, but sex never seemed to be at the heart of their relationship. They lived together, but Orton prowled the night streets for rough trade and Halliwell scolded him for taking too many chances. Orton was, by all accounts, a charming young man – liked by everybody, impish, rebellious, with a taste for danger. Halliwell, eight years older, was a stolid, lonely man who saw himself as Orton’s teacher.

He taught him everything he could. Then Orton used what he’d learned to write plays that drew heavily on their life together. His big hits were “Loot” and “What the Butler Saw,” and both are still frequently performed. But when Orton won the Evening Standard’s award for the play of the year – an honor like the Pulitzer Prize – he didn’t take Kenneth to the banquet, he took his agent.

Halliwell began to feel that he was receiving no recognition for what he saw as the sacrifice of his life. He dabbled in art and constructed collages out of thousands of pictures clipped from books and magazines. But his shows were in the lobbies of the theaters presenting Joe’s plays, and people were patronizing to him. That began to drive him mad.

“Prick Up Your Ears” is based on the biography that John Lahr wrote about Orton, a biography that has become famous for discovering a private life so different from the image seen by the public.

Homosexuality was a crime in the 1960s in England, but Orton was heedless of the dangers. In fact, he seemed to enjoy danger. Perhaps that was why he kept Halliwell around, because he sensed the older man might explode. More likely, though, he kept him out of loyalty and indifference and didn’t fully realize how much he was hurting him. One of the early scenes in the film shows Halliwell skulking at home, angry because Orton is late for dinner.

The movie is good at scenes like that. It has a touch for the wound beneath the skin, the hurt that we can feel better than the person who is inflicting it. The movie is told as sort of a flashback, with the Lahr character interviewing Orton’s literary agent and then the movie spinning off into memories of its own.

The movie is not about homosexuality, which it treats in a matter-of-fact manner. It is really about a marriage between unequal partners. Halliwell was, in a way, like the loyal wife who slaves at ill-paid jobs to put her husband through medical school, only to have the man divorce her after he’s successful because they have so little in common – he with his degree, her with dishwater hands.

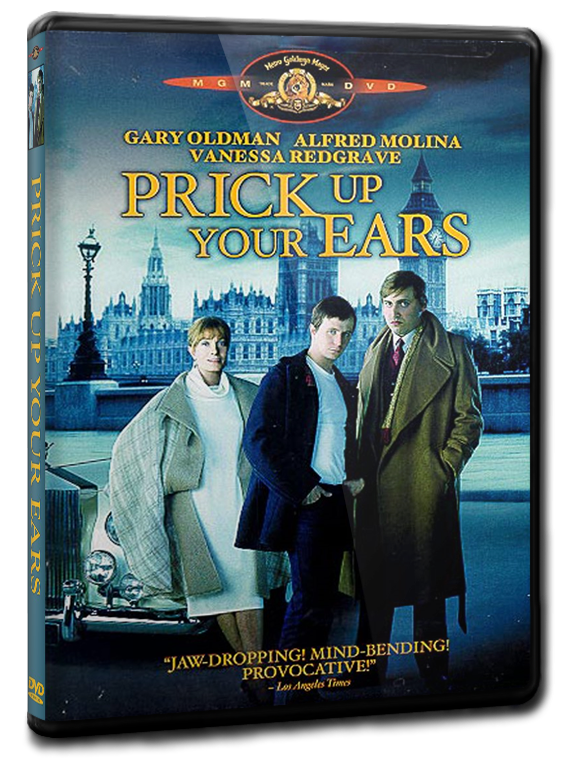

The movie was written by Alan Bennett, a successful British playwright who understands Orton’s craft. He bases one of his characters on Lahr (played by Wallace Shawn), apparently as an excuse to give Orton’s literary agent (Vanessa Redgrave) someone to talk to. The device is awkward, but it allows Redgrave into the movie, and her performance is superb: aloof, cynical, wise, unforgiving.

The great performances in the movie are, of course, at its center. Gary Oldman plays Orton and Alfred Molina plays Halliwell, and these are two of the best performances of the year. Oldman you may remember as Sid Vicious, the punk rock star in “Sid and Nancy.” There is no point of simularity between the two performances; like a few gifted actors, he is able to re-invent himself for every role. On the basis of these two movies, he is the best young British actor around. Molina has a more thankless role as he stands in the background, overlooked and misunderstood. But even as he whines we can understand his feelings, and by the end we are not very surprised by what he does.

The movie was directed by Stephen Frears, whose most recent movie, “My Beautiful Laundrette,” also was about a homosexual relationship between two very different men: a Pakistani laundry operator and his working-class, neofascist boyfriend. Frears makes homosexuality an everyday thing in his movies, which are not about his characters’ sexual orientation but about how their underlying personalities are projected onto their sexuality and all the other areas of their lives.

In the case of Orton and Halliwell, there is the sense that their deaths had been waiting for them right from the beginning. Their relationship was never healthy and never equal, and Halliwell, who was willing to sacrifice so much, would not sacrifice one thing: recognition for his sacrifice. If only Orton had taken him to that dinner, there might have been so many more opening nights.